ANITA COBBY: THE NURSE WHO CHANGED A NATION

The last person to see Anita Cobby alive was a bartender who would spend the next forty years wishing he’d offered her a ride home.

It was February 2, 1986—a Monday night in Sydney when the summer heat had finally broken and the air held that rare, breathable quality that makes people linger over their goodbyes. Anita, twenty-six years old and radiating the kind of beauty that makes strangers remember you years later, had just finished a long shift at Blacktown Hospital. She’d joined colleagues for dinner at a local restaurant, laughing over hospital gossip and cold beers, her nurse’s uniform exchanged for jeans and a light blouse.

She left at 8:30 p.m., saying she needed to catch the train home.

“I’ll be fine,” she told a friend who offered to walk her to the station. “It’s just two blocks.”

Those would be among her last recorded words.

The Woman Behind the Headlines

Before Anita Lorraine Cobby became a name etched into Australia’s darkest history, she was the daughter who called her mother every Sunday without fail. The wife trying to figure out if a separation could become a reconciliation. The nurse who stayed late when a patient was frightened, even if it meant missing the earlier train.

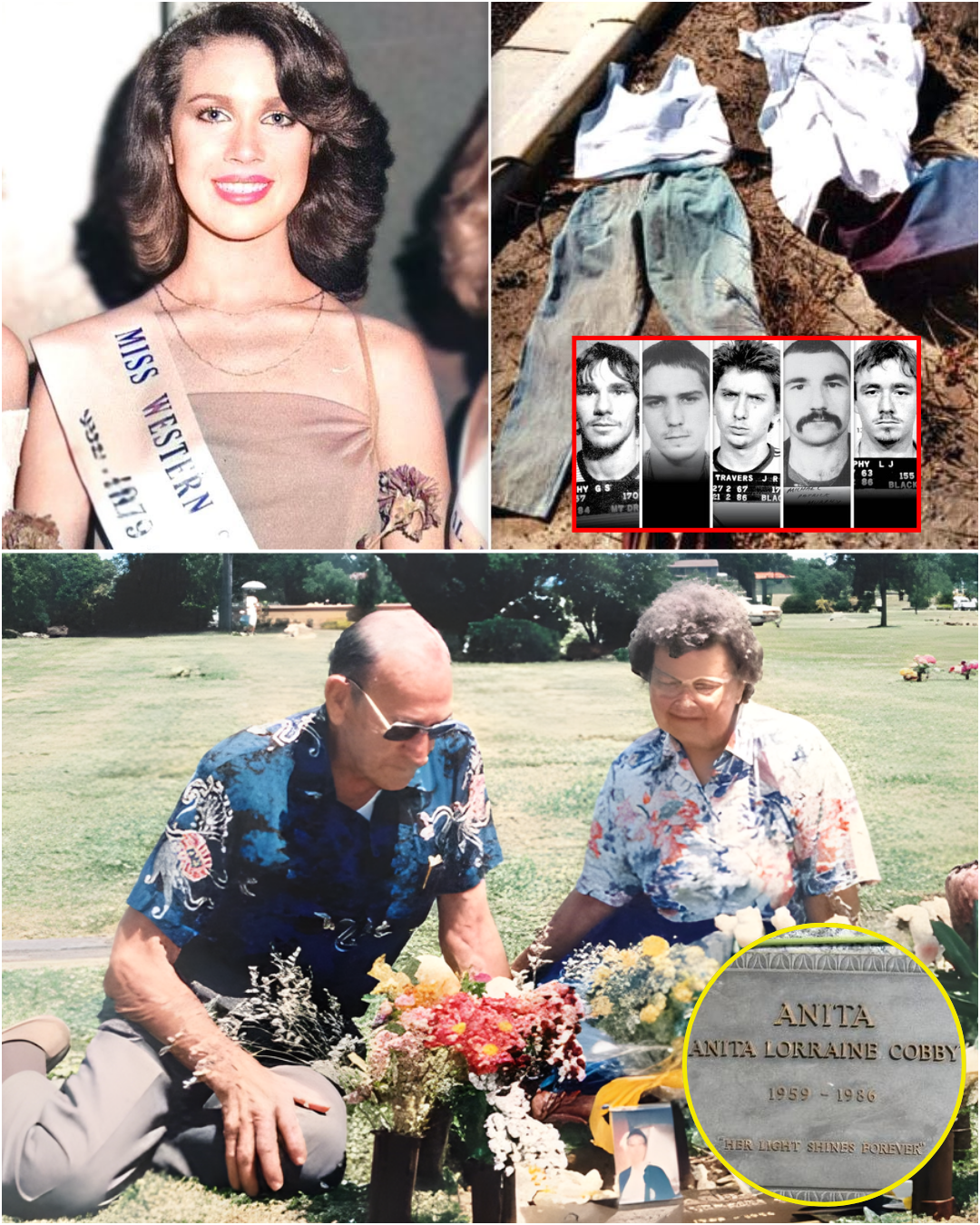

She’d won a beauty pageant at seventeen—Miss Western Suburbs, a title that came with a sash and local fame—but turned down modeling contracts to study nursing. When friends asked why, her answer was characteristically simple: “Beautiful things fade. Helping people doesn’t.”

At Blacktown Hospital, patients remembered her hands before they remembered her face. Warm hands. Steady hands. The kind that didn’t flinch when inserting an IV on the third try or holding a basin while someone retched. She worked the overnight shifts nobody wanted, the weekends when families fell apart in waiting rooms, the holidays when being sick felt like a double punishment.

Her marriage to John Cobby had been a love story that moved too fast—engaged after four months, married before their first anniversary, separated before their second. They were young and stubborn and loved each other in that fierce, clumsy way that burns bright and hot. The separation wasn’t hateful; it was human. They still talked. Still met for coffee. Still held onto the hope that maybe, with a little time and space, they could figure out how to be gentler with each other.

On that Monday night, John was at home waiting for a phone call that would never come. They’d planned to talk that week about trying again.

The Train That Never Arrived

The 9:12 p.m. train from Blacktown Station ran reliably—a silver link in Sydney’s transit chain that carried office workers, students, and nurses like Anita between the city and its sprawling western suburbs. The platform was well-lit, familiar, safe in the way routine makes things safe.

Except when it isn’t.

Somewhere between the restaurant and her parents’ home in nearby Prospect—a journey she’d made hundreds of times—Anita vanished. No scream. No witness. No clue beyond the absence of her arrival.

Her father, Garry Lynch, checked his watch at 10:00 p.m. Then 10:30. At 11:00, he called the hospital. No, they said, she’d left hours ago. He called John. No, she hadn’t stopped by. He called the restaurant. The bartender remembered her leaving alone, remembered thinking she looked tired but happy, remembered nothing else useful.

By midnight, Garry was driving the route between Blacktown and Prospect with his headlights on high, scanning ditches and side streets, calling her name into the dark like a prayer.

At 2:00 a.m., he called the police.

The desk sergeant took the report with the weary efficiency of someone who’d filed a hundred just like it. Young woman. Twenty-six. Last seen leaving a restaurant. Probably stayed with a friend. Probably forgot to call home. Probably fine.

Probably.

What the Cattle Found

John Reen was a dairy farmer who’d worked the same land outside Sydney for thirty years. He knew his herd the way a conductor knows an orchestra—which cow led, which lagged, which one got anxious when storms rolled in from the coast.

On the morning of February 4, two days after Anita disappeared, his cattle wouldn’t move past a certain section of fence line. They clustered there, shifting and lowing, their massive heads turned toward something in the field beyond.

Reen walked over to see what had spooked them.

What he found would haunt him until the day he died.

Anita’s body lay in a shallow paddock, discarded like refuse. She’d been beaten, tortured, and violated with a savagery that defied comprehension. The medical examiner would later testify that her injuries suggested she’d survived for hours—conscious, aware, fighting until she couldn’t fight anymore.

The crime scene told a story written in tire tracks and footprints, in the geography of violence that investigators would piece together over weeks. A white car. A lonely road. Five men who’d seen a woman walking alone and made a choice that would cost them their freedom and cost Anita everything.

The Investigation Begins

Detective Sergeant Ian Kennedy had worked homicide for twelve years. He’d seen bodies pulled from the harbor, found in burned-out cars, left in motel rooms with needles still in their arms. He thought he’d developed the emotional calluses necessary for the job.

He was wrong.

“This one’s different,” he told his partner after viewing the scene. His hands shook as he lit a cigarette—a habit he’d quit two years earlier. “We find who did this, or I hand in my badge.”

The investigation moved with the controlled fury of professionals who knew they were racing against time and public panic. Sydney’s western suburbs were already on edge—a series of unsolved assaults, a growing sense that the streets weren’t as safe as they’d been a generation ago.

Now a nurse—a beautiful, kind, beloved nurse—had been murdered within walking distance of a major train station.

The phones at police headquarters didn’t stop ringing. Tips poured in from bartenders, cab drivers, the late-night clerk at a petrol station who remembered a white sedan with a dented fender. A teenager came forward with a story that made Kennedy’s blood run cold: he’d been looking out his bedroom window that Monday night and saw a woman being forced into a car near Blacktown Station. He’d told his mother, who’d dismissed it as kids fighting.

“I should have called,” the boy said, crying. “I should have called right then.”

Kennedy put a hand on his shoulder. “You’re calling now. That matters.”

The White Car

Stolen vehicle reports are the background noise of any police station—hundreds filed each week, most recovered within days, usually by teenagers joyriding or opportunistic thieves looking for quick cash.

This one was different.

A white Honda Civic, reported stolen from a shopping center parking lot on February 1, matched the description from three separate witnesses. Primer showing through the paint job. Dent above the left taillight. A belt that squealed when accelerating.

The registration led to a panel shop in Mount Druitt, a working-class suburb where poverty and pride lived side by side in weatherboard houses with chain-link fences. The shop’s owner remembered the car—and more importantly, he remembered the men who’d brought it in for off-the-books work.

Five names. All with criminal records. All known to police for petty theft, assault, breaking and entering.

Detective Kennedy spread their files across his desk like tarot cards reading a terrible future.

Gary Murphy: 28 years old, the oldest of the group. Charming smile. Dead eyes. Previous convictions for assault and theft. Known to brag about crimes in pubs, buying rounds and telling stories to impress younger men.

Les Murphy: Gary’s younger brother, 22, eager to prove himself, already collecting a record that would keep him unemployed and angry.

Michael Murphy: No relation, but drawn into the brothers’ orbit by some magnetic pull that violence exerts on certain young men. Nineteen years old. Hadn’t finished high school. Worked odd jobs when he worked at all.

John Travers: Twenty-five, handsome in a way that had always gotten him out of trouble until it didn’t. The kind of charisma that reads as confidence but is really just hunger for attention at any cost.

Michael Murdoch: The youngest at eighteen. Slight build. Nervous laugh. The one who’d follow because following felt easier than thinking.

“Bring them in,” Kennedy ordered. “All of them.”

The Confession on Tape

When you watch enough guilty men sit across an interrogation table, you learn to read the silences. Some fidget. Some stare. Some try to fill the quiet with words that dig their graves deeper.

Michael Murdoch did all three.

“I don’t know anything,” he said, leg bouncing under the table. “I wasn’t even there.”

“Where weren’t you?” Kennedy asked.

“Wherever you think I was.”

It’s a common slip—answering the question they’re afraid you’ll ask rather than the one you did ask. Kennedy let it hang in the air for five seconds, then ten. Murdoch’s leg bounced faster.

“The car,” Kennedy said finally. “The white Honda. You know it?”

“Lots of people have Hondas.”

“This one was stolen. This one was seen near Blacktown Station on Monday night. This one has your prints on the passenger door.”

Murdoch’s face collapsed like wet paper. “I didn’t hurt her. I swear to God, I didn’t touch her.”

Kennedy leaned forward. “So you know who we’re talking about.”

The confession came in pieces—first from Murdoch, then from physical evidence, then from a girlfriend of John Travers who’d grown tired of sleeping next to a man who bragged about murder.

She wore a wire into a pub on February 10. The recording would later be played in court, and even the judge—a man who’d presided over hundreds of violent cases—would need to take a recess.

Travers talked about the abduction like it was a fishing story. Talked about what they did to Anita in language so crude and proud that the girlfriend in the wire had to excuse herself twice to vomit in the pub bathroom. When she returned, he was still talking, buying rounds for strangers, his voice getting louder with each beer.

“She fought,” he said, laughing. “I’ll give her that. She had some spirit.”

The girlfriend left the pub, drove straight to the police station, and handed over the tape recorder with hands that wouldn’t stop shaking.

“I’m sorry I waited this long,” she whispered.

Kennedy took the tape. “You didn’t wait. You’re here now.”

The Arrests

They came for them at dawn—five houses, five teams, five sets of handcuffs clicking shut in the gray early light.

Gary Murphy answered his door in boxer shorts, cigarette between his lips, and said, “I knew you’d come.” He didn’t resist. Didn’t ask for a lawyer. Just put his hands behind his back and said, “Let’s get this over with.”

His brother Les tried to run, made it three houses down before a constable tackled him into someone’s front garden. The homeowner came out with a cricket bat, ready to defend his roses, then saw the uniforms and backed away.

Michael Murphy was asleep. Woke to hands pulling him from bed, shouting about rights he barely understood, sobbing before they’d even gotten him to the car.

John Travers put up a fight—fists swinging, voice screaming about police brutality and false charges and knowing people who’d make this all go away. It took three officers to subdue him, and even then he kept talking, kept threatening, kept trying to be the biggest voice in every room.

Michael Murdoch was at his mother’s house. She answered the door, saw the badges, and knew. Mothers always know. She called for her son, and when he appeared at the top of the stairs—skinny, scared, eighteen years old—she said only, “Michael. What did you do?”

He couldn’t answer. Just walked down the stairs and into custody while his mother stood in the doorway, still as stone, a rosary clutched in one hand.

By noon, all five were in holding cells.

By evening, Australia knew their names.

The Nation Watches

By the time the trial began on March 16, 1987, Australia had already convicted the five men in the court of public opinion. The question wasn’t guilt—the evidence was overwhelming, the confessions damning—but whether the justice system could deliver a punishment that matched the magnitude of the crime.

The courtroom in Sydney’s Supreme Court building was packed daily with reporters, family members, and citizens who’d taken time off work to witness what many called the trial of the decade. Outside, protesters carried signs demanding the return of capital punishment, which Australia had abolished nearly two decades earlier. Inside, the Lynch family sat in the front row, Grace holding Garry’s hand with a grip that never loosened, even during the worst testimony.

Minutes before proceedings were set to begin, John Travers stunned the court by changing his plea to guilty. It wasn’t remorse—not in any way that mattered. His lawyer would later explain it as a strategic decision, a calculation that accepting responsibility might somehow soften what was coming. It didn’t work.

The Sydney tabloid The Sun couldn’t help itself. On the day the trial began, they ran a front-page headline: “ANITA MURDER MAN GUILTY,” alongside a photograph of Travers large enough to fill a billboard. A follow-up story detailed Michael Murphy’s recent escape from Silverwater Correctional Centre, where he’d been serving 25 years for burglary. He’d been out less than a month when Anita was murdered.

The judge had no choice. The jury was discharged due to prejudicial publicity. A new jury was empaneled. The trial would start again.

54 Days of Horror

The trial lasted 54 days—nearly two months of testimony so graphic that court reporters would step outside to breathe, that jurors would request breaks, that even the bailiff—a man who’d worked violent crime cases for fifteen years—had to excuse himself during the medical examiner’s testimony.

Dr. Peter Bradhurst, the medical examiner, spoke in the clinical language doctors use when emotion would be too expensive to afford. He described extensive bruising consistent with “a systematic beating.” He noted the lacerations from barbed wire where she’d been dragged. He detailed the cuts to her throat that severed her windpipe and nearly decapitated her.

The defense’s strategy was simple: minimize individual involvement. Each lawyer argued his client had been the least culpable, the one who’d hesitated, the one who’d tried to stop the others. It was mathematically impossible for all five to have been the least involved, and the jury knew it.

The prosecution presented the physical evidence first—fibers from the stolen car found on Anita’s clothing, soil samples from the field that matched dirt on the defendants’ shoes, fingerprints that placed each man at the scene. Then came the testimony that would haunt the courtroom: the girlfriend’s tape recording of Travers bragging in explicit, stomach-turning detail about what they’d done.

When the tape was played, Grace Lynch closed her eyes. Garry stared straight ahead, jaw clenched so tight a muscle twitched in his cheek. John Cobby—who’d been sober for three weeks—left the courtroom and didn’t return for two days. When he came back, he smelled like whiskey and defeat.

The defense tried to argue the tape was bravado, exaggeration, the kind of story young men tell to impress women in bars. The prosecution pointed out that every detail on the tape matched the evidence: the location, the sequence of events, the injuries.

On June 10, 1987, after weeks of testimony and days of deliberation, the jury returned.

Guilty on all counts.

All five men. Sexual assault. Murder.

In the gallery, people wept. Not from relief—there is no relief in a case like this—but from the simple fact that the truth had been spoken aloud and recorded into permanence.

“Never to Be Released”

On June 16, 1987, Justice Alan Maxwell stood to deliver the sentences. He was 62 years old, a veteran of the bench who’d presided over hundreds of criminal cases. He’d never spoken words like these before.

“This was one of the most horrifying physical and sexual assaults,” he began, his voice steady but heavy. “This was a calculated killing done in cold blood”.

He sentenced each of the five men to life imprisonment without the possibility of parole.

Then he did something extraordinary. He requested that each of their files be marked with four words: “Never to be released”.

It was the closest thing to a death sentence the Australian legal system could deliver. The men would die in prison—not by execution, but by time and its slow, grinding certainty.

In the gallery, Grace Lynch nodded once, a small gesture that contained multitudes.

Outside the courthouse, the crowd that had gathered—hundreds strong—stood in silence as the convicted men were led to transport vans. No one cheered. No one jeered. They simply watched, bearing witness to the moment evil was named and contained.

The Long Road Home

John Cobby tried to rebuild a life from the wreckage. For the first year, he succeeded in brief, fragmented ways—a week sober, then a collapse; a new job, then too many sick days; a date with a kind woman who looked nothing like Anita, then the guilt of laughing at her joke.

He attended counseling sessions that felt like confessions to a crime he didn’t commit. The therapist asked him what he was feeling. He said, “Nothing,” which was a lie. He was feeling everything, all at once, a tidal wave of rage and grief and the terrible suspicion that if he’d tried harder to reconcile, if he’d offered to drive her home that night, if he’d loved her better when he had the chance, she’d still be alive.

“You can’t think like that,” the therapist said gently.

“Then tell me how to think,” John snapped back.

There was no answer because there isn’t one. Grief is not a problem to be solved. It’s a country you live in now, with different laws and a language you have to learn from scratch.

Eventually, John remarried—a woman who understood that some rooms in a person’s heart stay furnished for ghosts. They had a son together. He named him something new, not carrying forward any family names, because the boy deserved to be his own person, not a memorial.

On anniversaries of Anita’s death, John would drive to Blacktown and sit in his car near the station where she’d waited for a train that never came. He didn’t cry anymore. He’d used up all those tears in the first five years. He just sat, remembering the girl who’d reached for his hand at red lights, and promised her out loud: “I’m okay. I’m still here.”

What Grace and Garry Built

The Lynches could have retreated into private grief. Many families do. The world would have understood. Instead, they chose to build something.

In 1993—seven years after Anita’s murder—Grace and Garry Lynch partnered with Christine and Peter Simpson, whose daughter Ebony had also been murdered, to create the Homicide Victims Support Group (Australia). It started in a borrowed office with two folding chairs, a telephone, and a mission statement written on the back of a bank deposit slip: To help families survive the unsurvivable.

The phone rang constantly. Families who’d just lost someone. Families still waiting for trials. Families whose cases had gone cold and who needed someone to say, “I haven’t forgotten. Your child’s name still matters.”

Grace and Garry showed up for every call, every meeting, every court appearance. They sat with parents in hospital waiting rooms and police stations. They helped navigate victim impact statements and parole hearings. They testified before lawmakers about sentencing reform, arguing for truth in sentencing laws that would prevent violent offenders from being released early on technicalities.

“People don’t understand what it’s like,” Grace told a reporter in 1995. “Until you get that knock on the door, until you hear those words—your child is gone—you can’t imagine it. We can. That’s why we do this”.

They campaigned tirelessly for legislative changes. Their advocacy contributed to tougher sentencing laws, mandatory minimum sentences for violent crimes, and reforms ensuring that “life imprisonment” actually meant life.

Garry Lynch passed away in 2008 at age 90, his mind clouded by Alzheimer’s, but Grace said he died knowing their work mattered. Grace continued the mission until her own death from lung cancer in 2013 at age 88. They’d been married 54 years.

Grace’s Place

The final dream—the one Grace and Garry started planning in the early 2000s but didn’t live to see completed—was a facility specifically for children affected by homicide.

Grace’s Place, named in honor of Grace Lynch, officially opened in 2022 in Blacktown. It’s a world-first residential trauma center designed for kids who’ve lost a parent, sibling, or caregiver to murder—a specialized kind of grief that standard counseling often fails to address.

The building sits on donated land, painted in soft colors that don’t remind anyone of hospitals or police stations. Inside, there are art therapy rooms, quiet spaces for one-on-one counseling, and group areas where teenagers can talk about the specific hell of being known at school as “the kid whose mom was killed”.

Trained trauma specialists work with families for weeks or months, helping children process not just grief but guilt, rage, fear, and the strange dissonance of living in a world that continues as if nothing happened. They teach coping mechanisms. They help kids write victim impact statements if they want to. They sit with them during nightmares.

At the entrance, a plaque reads: “In memory of Anita Cobby and in honor of Grace and Garry Lynch, who turned loss into love”.

The Legacy

Anita Cobby’s name became shorthand in Australia for a specific kind of horror—the randomness of violence, the failure of safety in familiar places. But her legacy is not the crime. It’s what came after.

Nurses at hospitals across Australia still invoke her name when walking colleagues to their cars after night shifts. Her case led to increased lighting at train stations, emergency call boxes, and public awareness campaigns about the importance of community vigilance.

The four surviving killers remain in prison. Michael Murphy died in 2019 at age 65 from cancer, still behind bars at Long Bay jail hospital. Gary Murphy, Les Murphy, John Travers, and Michael Murdoch are held in undisclosed maximum-security facilities, their files still marked “never to be released”.

Periodically, one of them appeals their conviction or sentence. Each time, the public outcry is swift and fierce. Each time, the appeals are denied.

In 2016, on the 30th anniversary of Anita’s death, a memorial service was held at the site where Grace’s Place would eventually be built. Hundreds attended—former patients who remembered Nurse Cobby’s gentle hands, childhood friends, strangers who simply wanted to say her name aloud in a context other than crime.

John Cobby attended, elderly now, walking with a cane, but steady. When asked by a reporter what he wanted people to remember, he said: “That she was kind. That she chose to help people. That’s who she was before everything else”.

What Remains

There is no neat conclusion to a story like this. Anita Cobby didn’t die for a reason—there is no reason that justifies what was done to her. But her family refused to let her death be the final word.

Because of Grace and Garry Lynch’s tireless advocacy, hundreds of families have received support through their darkest hours. Because of legislative reforms they championed, violent offenders face stricter sentences and genuine accountability. Because of Grace’s Place, traumatized children have a sanctuary designed specifically for their unique pain.

In Blacktown, there’s a park where children play beneath jacaranda trees that bloom purple every spring. A small plaque near the path carries her name, not as a victim, but as a nurse, daughter, and friend whose kindness endures.

At Westmead Hospital, a scholarship in Anita’s name is awarded annually to a nursing student who demonstrates exceptional compassion. The recipients carry her legacy forward into hospital rooms where frightened patients need steady hands and someone who genuinely cares.

And across Australia, when parents walk their daughters to cars after dark, when communities install better lighting near transit stations, when families of homicide victims find support instead of isolation—Anita’s presence is there, quiet but insistent, a reminder that love can be stronger than the worst thing that ever happened.

The five men who killed her are footnotes now, their names fading with each passing year.

But Anita Lorraine Cobby—the nurse who stayed late to comfort frightened patients, the daughter who called home every Sunday, the woman who chose compassion over fame—her name remains, spoken not in fear but in gratitude for the grace her family built from grief.

Justice Alan Maxwell said during sentencing that the perpetrators should receive “the same degree of mercy they bestowed on their victim”. They received none. They will die in prison.

But mercy took a different form—in the support groups that hold grieving families, in the trauma center that heals wounded children, in the legislative reforms that protect communities, and in the thousands of nurses who continue Anita’s work with the same steady compassion she showed every single day of her short, luminous life.

That is the story Australia tells itself now. Not the horror of February 2, 1986, but the grace that came after. Not the darkness, but the lights that were turned on because of her.

In memory of Anita Lorraine Cobby (November 2, 1959 – February 2, 1986)

Nurse. Daughter. Friend. Her kindness endures.

News

The Face Hidden in Every Frame: The Jennifer Kesse Mystery

The Morning That Changed Everything A Life Built with Purpose The January sun rose over Orlando, Florida, painting the sky…

“What Really Happened to the Springfield Three? Inside America’s Greatest Unsolved Mystery”

The Last Normal Night The summer air hung thick and sweet over Springfield, Missouri, on the evening of June 6,…

After 46 Years, DNA Finally Whispered His Name: The Carla Walker Murder That Refused to Stay Cold

A Valentine’s Dance, A Stolen Life, and Nearly Half a Century of Waiting for Justice February 17, 1974, started like any other Sunday…

After 46 Years, DNA Finally Whispered His Name: The Carla Walker Murder That Refused to Stay Cold

A Valentine’s Dance, A Stolen Life, and Nearly Half a Century of Waiting for Justice February 17, 1974, started like any other Sunday…

The Hart Family Tragedy: The Perfect Instagram Family That Hid a Decade of Horror Before Driving Off a Cliff

When “Free Hugs” Became a Funeral Shroud: The Untold Story America Needs to Hear On March 26, 2018, a German…

“Kidnapped in Cleveland: The True Story of Three Women Who Refused to Give Up Hope After a Decade in Hell”

The morning of August 23, 2002, started like any other desperate morning in Michelle Knight’s life. She stood in…

End of content

No more pages to load