His voice comes slow, cracked like an old floorboard.

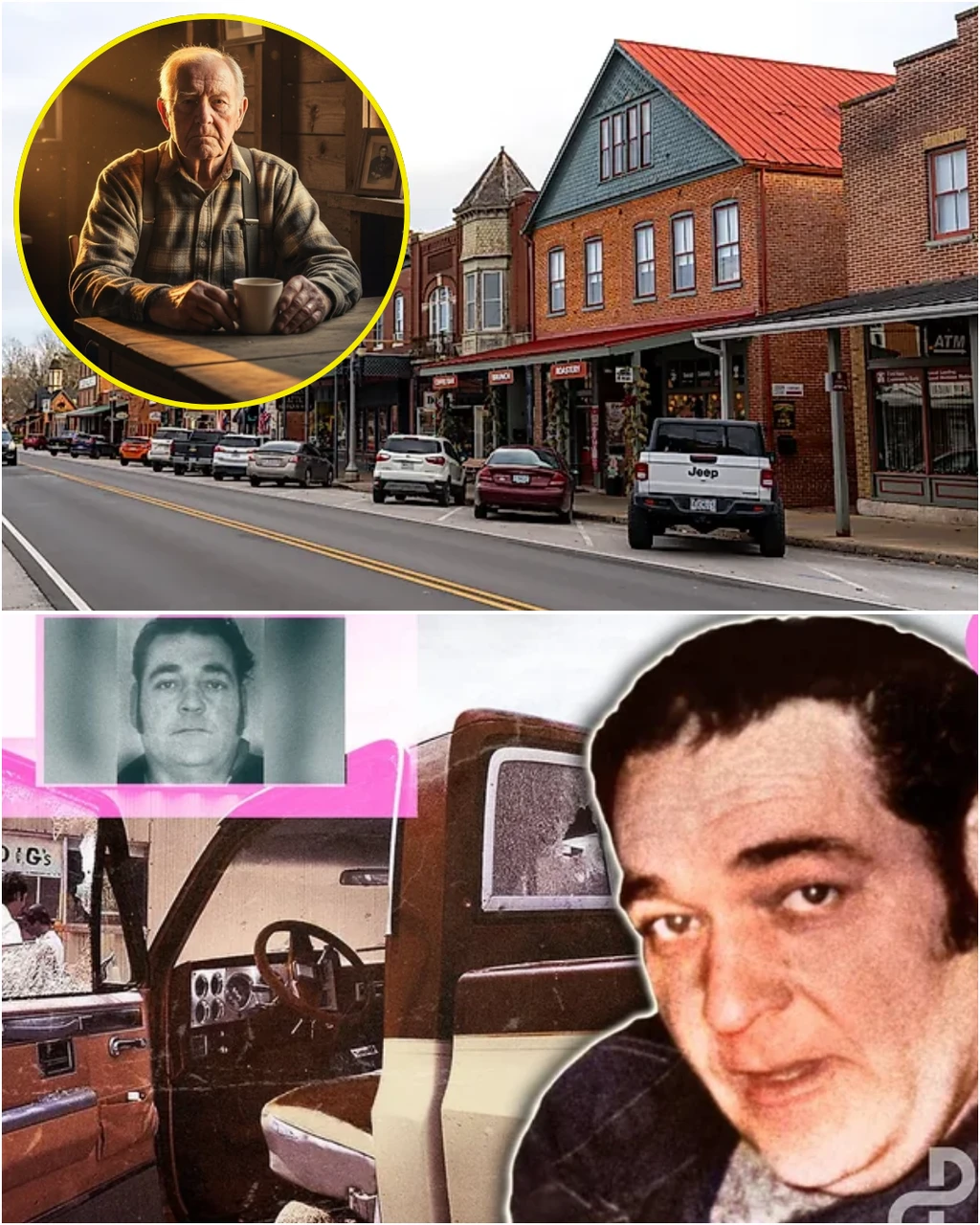

He sits by the window of a wooden farmhouse on the edge of what used to be Skidmore’s main street. Morning light filters through thin curtains, painting gold over dust and time.

He is eighty-nine now — the last man alive who stood there that day.

The last witness to a silence that has lasted four decades.

Outside, the town has faded to whispers.

The D&G Tavern where men once drank and argued is boarded shut. The grocery store, where Bo Bowenkamp once stocked shelves, now stands hollow, its windows clouded with dust. The church still rings its bell on Sundays, but fewer voices answer.

He wraps his hands around a chipped mug of coffee, steam rising between the lines of his fingers.

“They say we all looked away,” he murmurs. “Maybe we did. But when you live scared that long, looking away feels like breathing. You don’t even notice when it starts to kill you.”

For twenty years before that July morning, Skidmore had lived under one man’s shadow — Ken Rex McElroy, a 270-pound farmer turned predator who learned how to twist the law until it broke around him.

He never held office. Never wore a badge. But he ruled the town like a feudal lord.

If he wanted your land, he took it.

If he wanted your cattle, they disappeared.

If you dared to complain, he parked his truck outside your house all night, headlights off, cigarette burning behind the windshield.

You’d call the sheriff. The sheriff would come.

They’d talk on the porch. Then the sheriff would leave.

McElroy stayed.

And so, slowly, the town stopped calling.

The man by the window — his name we’ll keep unspoken — remembers those nights clearer than he wishes.

The way every knock on the door after dark made hearts race. The way neighbors stopped visiting, afraid to be seen together. The way their children learned too early that justice was something you hoped for, not something you got.

“First time, you tell yourself it’s just one man,” he says. “Second time, you tell yourself it’s not worth the trouble. By the third, you stop telling yourself anything at all.”

Psychologists might call it learned helplessness.

He calls it Tuesday night.

For a time, they thought the law would work.

Twenty-one indictments came and went. McElroy walked away from every one.

His lawyer, Richard Gene McFadin, was a master of delay. Each postponed hearing gave McElroy more time to stare down witnesses, to sit outside their homes in silence until courage turned to ash.

The system required bravery from people who had already run out of it.

“He didn’t threaten you,” the old man says. “He didn’t have to. He’d just sit there in that truck. You’d see the barrel of a rifle on the seat next to him. That was his language. Silence and waiting.”

Children grew up whispering his name like a curse.

Men carried shotguns to bed.

Women double-locked their doors before sunset.

And still, he walked free.

The morning that would change everything began like any other — the hum of cicadas, the shimmer of heat across endless fields. McElroy had been convicted of shooting old Bo Bowenkamp in the neck.

A miracle that Bo survived. A tragedy that the shooter was out on bail within days.

“He was in town, laughing about it,” the old man says, voice sharpening for the first time. “Rifle in his truck. Told everyone he’d finish the job soon. Said it right there in the tavern.”

They went to Sheriff Dan Estes, begged him to do something.

The sheriff looked tired, beaten.

He told them to “form a neighborhood watch.”

Then he got in his car — and drove away.

“That’s when I knew,” the witness says quietly. “If anything was going to change, it wouldn’t be because of the law.”

At 10 a.m., McElroy walked out of the D&G Tavern, his young wife Trena beside him.

He climbed into his pickup, engine idling in the July heat.

Across the street, dozens of townspeople watched from storefronts, doorways, cars.

No one said a word.

“He looked around, like always,” the old man remembers. “Like he owned the air we were breathing. Then he smiled — that same smile that said he’d gotten away with it again.”

Silence.

Then motion.

Then more silence.

What happened next is still debated by journalists, by philosophers, by people who weren’t there.

Those who were don’t debate at all.

He takes a long breath, eyes distant, the past alive behind them.

“I never saw who did it,” he says finally. “None of us did. That’s the truth we all agreed on.”

Outside, the wind moves through the cornfields, whispering against the boards of his house.

After that morning, Skidmore fell into a silence deeper than fear — a silence chosen, shared, protected.

“We didn’t talk because talking would’ve broken what we had left,” he says.

“You can’t rebuild peace with noise.”

He calls it the slow kind of evil.

The kind that doesn’t announce itself with blood, but with silence.

“Ken never had to pull a trigger to make you obey,” the old man says.

“He just had to show up.”

For two decades, that was how it went. McElroy stole livestock, torched barns, stalked anyone who spoke against him. The law turned into a revolving door. His lawyer, Gene McFadin, filed delay after delay until witnesses forgot what courage felt like.

It wasn’t one act that broke Skidmore. It was thousands of small humiliations. Each time someone stayed quiet, the fear thickened until it clung to everything: church pews, grocery aisles, supper tables.

By the late 1970s, parents warned their children: don’t look at him, don’t talk about him, and whatever happens, don’t get involved.

The man by the window rubs his palms together. “You start telling yourself keeping your head down is smart,” he says. “But one day you wake up and realize it’s cowardice wearing reason’s clothes.”

When McElroy shot Bo Bowenkamp, a seventy-year-old grocer, that illusion shattered. Bo lived. The town’s belief in law didn’t. McElroy laughed his way out of court on bail, rifle in hand, boasting he’d finish what he started.

Sheriff Estes told them to form a neighborhood watch—and drove away.

“That’s when something inside all of us snapped,” the old man says. “Not in anger. In clarity.”

The morning of July 10, 1981, felt hotter than the sun itself. At the American Legion Hall, farmers and shopkeepers gathered, voices low, faces pale.

They didn’t plan murder. They planned to stop being victims.

When McElroy walked out of the tavern, Trena beside him, every sound died.

A dog barked. A truck door slammed. Then nothing but cicadas.

“He looked at us,” the witness recalls, “like he always did—like we were already beaten.”

Then came the moment. Quick, untraceable. No one ran. No one screamed.

When it was over, the smell of gunpowder hung in the summer air. Trena froze in the passenger seat. McElroy slumped over the steering wheel.

No one called an ambulance.

No one called the sheriff.

They stood there a long time, not in shock but in stillness, as if trying to understand what freedom was supposed to feel like.

That afternoon, the town went quiet. Reporters came. The FBI came.

Everyone asked the same question: Who pulled the trigger?

And every answer was the same:

“I didn’t see anything.”

A hundred voices, one story.

Perfect silence.

To outsiders it looked like conspiracy. To those who lived it, it was communion.

“It wasn’t about hiding a killer,” the old man says. “It was about protecting what was left of our dignity.”

They buried fear in that silence. And like all burials, it demanded maintenance. For forty years, they’ve tended it—every Sunday sermon, every high-school reunion, every funeral where eyes meet and quickly look away.

“We all paid for that morning,” he says softly. “Just not with handcuffs.”

He turns his gaze back to the window, where sunlight has shifted toward evening.

“Some nights,” he adds, “I wonder if justice ever really showed up—or if it just changed its face and asked us to carry it for a while.”

He doesn’t call it guilt.

He calls it “the quiet that never leaves.”

For the first few months after that July morning, Skidmore seemed almost normal. People went back to their farms. Kids rode their bikes through Main Street again. At night, no headlights idled outside anyone’s house. No shadow lingered in the fields.

But the calm didn’t feel like peace.

It felt like holding your breath for too long.

“Reporters came from everywhere,” the old man says. “They asked the same things — who did it, how, why. We told them we didn’t see. We told them that every day until they stopped asking.”

That silence became the town’s second skin. It bound them together, but it also trapped them.

You could see it in the way people crossed the street to avoid questions, the way laughter died mid-sentence when strangers walked in.

“You live long enough with a secret like that,” he says, “and it stops being a secret. It becomes the air.”

Decades passed.

The world changed, but Skidmore stayed small — and smaller still.

The tavern where Ken McElroy had his last beer closed. The grocery store where Bo Bowenkamp had been shot was torn down. Young people left and didn’t come back.

“Maybe they wanted a town that didn’t carry ghosts,” the old man says.

He looks out at what’s left: fields, a handful of houses, the church steeple leaning slightly east.

“Skidmore died slower than Ken did,” he whispers. “Piece by piece.”

Historians and filmmakers kept returning, hoping to find a confession. They wanted someone to say I did it.

But no one ever has.

Not because they’ve forgotten.

Because they still remember too well.

That’s the burden of collective silence — it doesn’t fade; it fossilizes. It becomes the foundation under everything.

“People think silence is easy,” he says. “It’s not. It’s heavy. It’s something you carry every day so your neighbors don’t have to.”

He takes a long pause, the kind that belongs to someone measuring each word against the weight of time.

“I think we did what we had to do,” he says finally. “But the thing about doing what you have to… is that it never feels like victory.”

Outside, the wind presses against the walls, a soft hollow moan through the gaps of the old house. The sun is almost gone now. He hasn’t moved from his chair.

He says he doesn’t dream of that day anymore. What he dreams about are smaller things: the smell of diesel, the sound of the sheriff’s tires crunching gravel as he left, the look on Trena’s face — not shock, not grief, just a kind of quiet that mirrored their own.

“She didn’t deserve any of it,” he adds. “None of us did. But she had her silence too, in her own way.”

For a moment, he says nothing more. The tape recorder on the table hums faintly.

Then:

“People talk about justice like it’s something you can find in a courthouse.

Maybe it used to be.

But out here, justice was a field we had to plow ourselves.”

Forty-four years later, only one question lingers, drifting between guilt and grace:

When the law forgets to protect you, do you still have to obey it?

He doesn’t answer.

He just looks out at the dying light, the corners of his mouth tightening into something that isn’t quite a smile.

“I guess that’s for the rest of you to decide,” he says.

The tape clicks.

The wind sighs.

And the silence of Skidmore — the silence that once saved them — settles again, as if it never left.

✒️ Epilogue

Forty-six people saw what happened that morning.

Forty-five of them are gone.

The last one has finally spoken — not to confess, not to ask forgiveness, but to remind the world that good people, when pushed too far, don’t stop being good. They just stop waiting.

July 10, 1981. Skidmore, Missouri.

Forty-six witnesses. One secret. Forty-four years of silence.

And counting.

News

The Face Hidden in Every Frame: The Jennifer Kesse Mystery

The Morning That Changed Everything A Life Built with Purpose The January sun rose over Orlando, Florida, painting the sky…

“What Really Happened to the Springfield Three? Inside America’s Greatest Unsolved Mystery”

The Last Normal Night The summer air hung thick and sweet over Springfield, Missouri, on the evening of June 6,…

After 46 Years, DNA Finally Whispered His Name: The Carla Walker Murder That Refused to Stay Cold

A Valentine’s Dance, A Stolen Life, and Nearly Half a Century of Waiting for Justice February 17, 1974, started like any other Sunday…

After 46 Years, DNA Finally Whispered His Name: The Carla Walker Murder That Refused to Stay Cold

A Valentine’s Dance, A Stolen Life, and Nearly Half a Century of Waiting for Justice February 17, 1974, started like any other Sunday…

The Hart Family Tragedy: The Perfect Instagram Family That Hid a Decade of Horror Before Driving Off a Cliff

When “Free Hugs” Became a Funeral Shroud: The Untold Story America Needs to Hear On March 26, 2018, a German…

“Kidnapped in Cleveland: The True Story of Three Women Who Refused to Give Up Hope After a Decade in Hell”

The morning of August 23, 2002, started like any other desperate morning in Michelle Knight’s life. She stood in…

End of content

No more pages to load