The Saint and the Seed

La Crosse, Wisconsin, 1878.

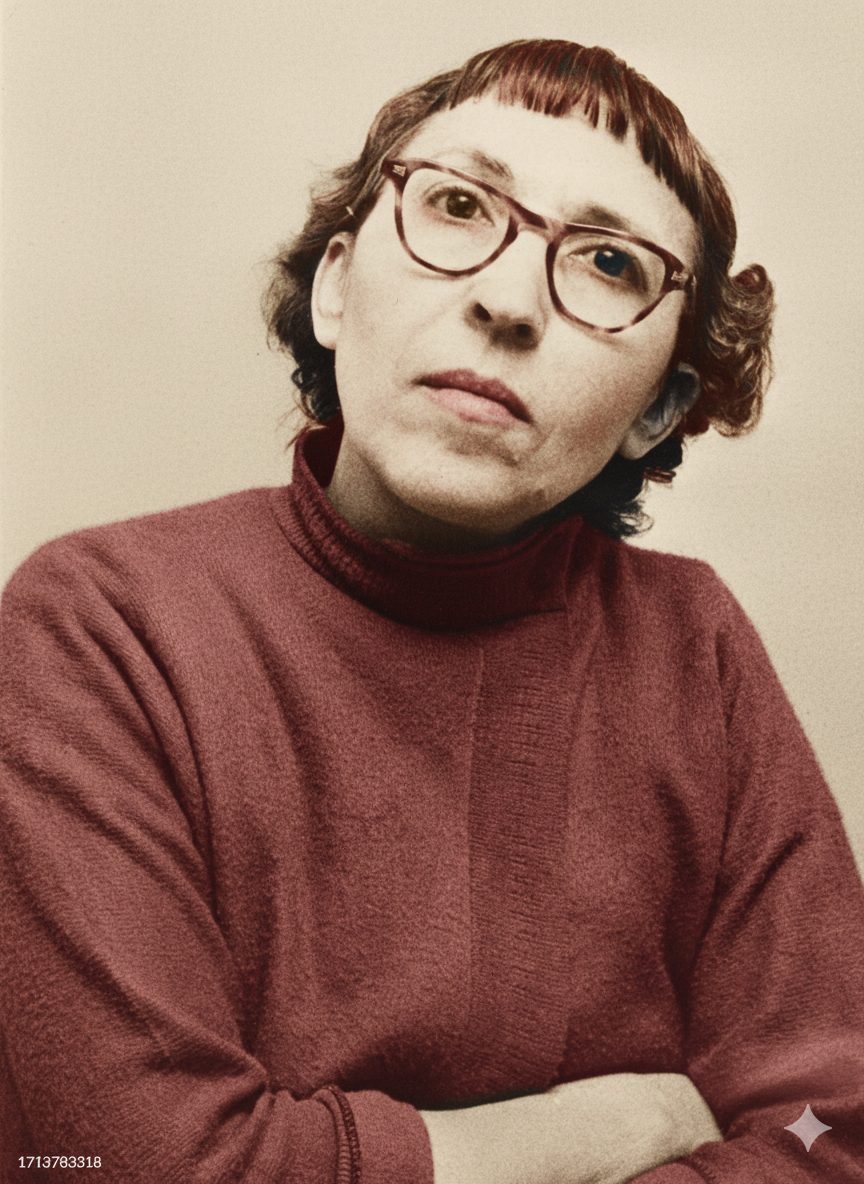

A child was born on a humid July night in a house that smelled of candle wax and sour milk. They named her Augusta Wilhelmine Gein, the daughter of poor German immigrants who measured sin more carefully than kindness. No one remembered her laughing. Even as a girl, she looked like someone carrying an invisible grievance against the world.

When Augusta grew up, she found God—then built a cage around Him. The Bible became less a book than a weapon. She read it as proof that pleasure was filth, that women were fallen, and that fear was the only road to salvation.

The Woman Who Never Smiled

In 1900 she married George Philip Gein, a timid, alcoholic carpenter who trembled when she raised her voice. Neighbors said she never touched him unless she had to. Two sons followed: Henry George in 1901 and Edward Theodore in 1906. Augusta wanted a daughter; when another boy arrived, she called it God’s test.

From the beginning she ruled her household like a priestess. Her word was divine law. Her husband, dull and useless, disappeared into the bottle; her sons became acolytes. She saw the outside world as a sewer of temptation. To save her family, she would cut them off from it completely.

Around 1915 she moved them to a remote farm on the edge of Plainfield, Wisconsin—a flat, wind-scoured patch of nothing surrounded by marsh and silence. To her, isolation was purity. To everyone else, it was exile.

Scriptures of Poison

Every night after supper, Augusta lit a kerosene lamp and read from Revelation, Leviticus, Proverbs—the angriest chapters. Her sermons were steady, venomous.

“The world is filth. Women are the root of man’s corruption. Lust is the devil’s breath.”

The boys listened because there was nothing else to listen to. Outside, the wind howled across the fields; inside, her voice filled every corner of the dark wooden house.

For Edward—quiet, thin, inward—those words became law. He was taught to fear women, to despise desire, and to believe that his mother alone stood between him and damnation. Augusta’s religion was not faith but domination. She turned obedience into worship, and her son’s love into submission.

The Child Who Wasn’t Allowed to Live

Plainfield’s few children sometimes passed the Gein farm on their way to school. They waved. The younger boy never waved back. Augusta forbade it. “You will not speak to the damned,” she said.

When he once looked too long at a girl in town—a harmless glance at a smile—his mother made him kneel beside the stove until his knees blistered. Then she recited a psalm about impurity. He wept, not from pain but from shame.

Children are sponges. They absorb what the air gives them. Edward absorbed his mother’s fear until it became the shape of his own mind.

No Mirrors in the House

There were almost no mirrors inside the farmhouse. Augusta said they encouraged vanity. Instead, she kept crucifixes on every wall. The boy learned to see himself only through her eyes—never as a person, only as a reflection of sin or obedience.

Psychologists later called this identity diffusion. But there was nothing clinical about the way it felt. He existed only through her approval. When she praised him, the world made sense; when she scolded him, it shattered.

Henry, the older brother, sometimes rebelled—mocking their mother’s endless sermons, muttering that she was crazy. Augusta called him “ungrateful.” Edward called him “dangerous.”

Death Lessons

Augusta preached not just about sin but about death. She treated corpses as moral lessons. When livestock died, she would stand over the carcass, lay a hand on its stiff flank, and whisper,

“This is what sin looks like, Edward.”

He watched. He learned. Not fear, not disgust—just fascination. Skin, bone, decay: all evidence of God’s punishment. It would make sense later, though no one would wish for that understanding.

The House Tightens

The years folded in on themselves. Winters turned the farm into a white desert. Augusta’s voice grew harsher as her health failed. George Gein finally died in 1940—heart failure, exhaustion, or mercy, depending on who told it. At the funeral Augusta didn’t cry. She simply murmured, “The weak shall perish.”

Her younger son stood beside her, stiff as wood, waiting for permission to grieve. None came.

Something cracked inside him then—a silent fracture that never healed. He began speaking less, moving slower, staring longer at his mother’s face as if afraid it might vanish.

Fire and Jealousy

In 1944 a brush fire broke out near the property. The brothers tried to control it; when it was over, Henry was dead. Official cause: asphyxiation. Unofficial whispers: envy.

Neighbors recalled how Henry had criticized Augusta only days before, calling her “not a woman of God but a tyrant.”

Whether the younger brother killed him will never be proven. But when sheriff’s deputies told Augusta her eldest was gone, she simply nodded and said, “God has spoken.”

From that moment onward, the farmhouse belonged to two souls locked inside the same fever: one fading, one festering.

The Shrine of Fear

As Augusta’s health collapsed, Edward became her nurse. He fed her, washed her, prayed beside her bed. He slept in a chair outside her door like a sentry guarding a relic. She rewarded him with sermons—soft now, almost tender, yet still poisoned.

“Never trust women. Never leave me. The world will devour you.”

He nodded, his face pale in the lamplight. Outside, snow covered the fields. Inside, time stopped.

When she finally died on December 29, 1945, the farmhouse fell silent in a way it never had before. The air seemed to freeze mid-breath.

To most people, it was a death. To him, it was the end of the universe.

After the Saint

He built her a tomb inside the house. Locked her bedroom door. Left everything untouched—the Bible on the nightstand, the cross on the wall, the smell of her medicine.

No one was allowed in. Not even him. That room became sacred, untouchable, perfect.

The rest of the house began to rot. Dust, rats, filth—but behind that locked door, time stayed pure. He had preserved his mother the only way he could: by embalming her absence.

Neighbors saw him sometimes in town, quiet, polite, buying kerosene or pork rinds, laughing nervously at small jokes. Harmless, they thought. A little odd, maybe. They didn’t know he had stopped being a man years earlier.

Inside the farmhouse, the silence had started to speak back.

The Resurrection

The winter Augusta Gein died, Plainfield was covered in ice. The sky hung low and gray, and the snow on the Gein farm never melted, just compressed into something like stone.

Inside the house, the air didn’t move. Curtains stayed drawn. The clocks still ticked, but their rhythm no longer meant time — only repetition.

Edward Gein didn’t bury his mother in any meaningful sense. Her grave sat in the town cemetery, but her presence stayed in that locked room upstairs. He told himself he was keeping it clean for her. In truth, he was keeping it alive.

Twelve Years in the Tomb

Between 1945 and 1957, Plainfield forgot about Ed Gein. He became the town’s odd-job man: quiet, punctual, harmless. He fixed roofs, shoveled snow, repaired engines. People said he was “a little strange but polite.” He’d blush when women spoke to him, stammer when someone mentioned church.

No one suspected that when he went home each night, he was entering a world that had split away from theirs — a world designed to make death familiar.

Augusta’s room remained sealed, untouched. Dust never dared to fall there. The rest of the house turned into a cave of rot: newspapers from the 1930s stacked to the ceiling, jars of organs, dead rodents, a smell that never left.

But to Gein, it wasn’t filth. It was comfort. It was the smell of permanence.

The Voice of the Dead

He began reading pulp magazines and anatomy books scavenged from junk shops. Stories of Nazis, medical experiments, grave robbers. Somewhere between fascination and faith, he started to believe that the body was just another vessel — something that could be rearranged, repaired, reused.

People later said he heard voices. Maybe he did. Maybe it was just the echo of Augusta’s voice inside his skull, saying,

“Do not trust the living. The pure exist only in death.”

At first, he only visited the cemetery. He said he went to talk to his mother. But the visits grew longer. Then the shovel came.

The Night Harvest

Plainfield’s cemetery was small — rows of tilted headstones, snow-crusted and half forgotten. Gein knew it well. At night he moved like a shadow between the graves, guided by memory and moonlight. He chose women who “looked like his mother.”

He didn’t dig deep — just enough to break the skin of the earth. The soil was frozen, the coffins heavy. But he was patient. When the work was done, he would carry parts home wrapped in burlap, as if bringing groceries.

Later, when the police asked him why, he said:

“I wanted to feel her again. I wanted her back.”

He meant Augusta. He always meant Augusta.

The House of Silence

Inside the farmhouse, he built what one investigator later called “a museum of nightmare anthropology.” Chairs upholstered in human skin. Bowls made from skulls. A lampshade stitched from faces.

But even those grotesque details miss the real horror: it wasn’t lust or sadism that drove him. It was longing. He was trying to reassemble a feeling.

Each object was a prayer — twisted, obscene, but sincere. He wasn’t mocking the dead; he was resurrecting the only person he’d ever loved.

And so he built the unthinkable: a “woman suit” sewn from the flesh of those he exhumed. He would wear it at night, standing in front of the mirror, his reflection rippling in candlelight, whispering in a falsetto voice,

“I’m home, Mother.”

It was grief disguised as ritual, faith reborn as madness.

The Disappearing Women

Plainfield was too small for its ghosts to stay hidden. In December 1954, Mary Hogan, a tavern owner, vanished without a trace. She was loud, funny, coarse — the kind of woman Augusta would have called “a sinner.”

The bar closed early that night. There was blood behind the counter, a single spent bullet on the floor, and no body.

When people joked about it later, Gein would smile awkwardly and say, “She’s not missing, just at the farm.” They laughed. He didn’t.

Three years passed. On November 16, 1957, Bernice Worden, the owner of the local hardware store, also vanished. Her son, Deputy Sheriff Frank Worden, found the shop empty and blood on the floor. The last sales receipt read: “Antifreeze — Ed Gein.”

That was all it took.

The Discovery

That night, police went to the Gein farm. They broke through the door expecting a robbery suspect. What they found froze them in place.

Bernice Worden’s body hung upside down in the shed, gutted like deer. Inside the house, the stench was suffocating. There were skulls on bedposts, human organs in jars, and faces stretched over molds like grotesque masks. In the kitchen sink, a heart.

One officer fled outside to vomit. Another whispered, “This isn’t a crime scene. It’s a descent.”

When they reached Augusta’s sealed bedroom, they found it untouched — clean, dustless, preserved like a chapel.

The contrast was unbearable: chaos and rot on one side, sanctity on the other. It was the map of a mind divided in two halves — one dead, one diseased.

The Question Everyone Asked

Reporters from across the country descended on Plainfield. They called it “The House of Horrors.” But psychologists asked a different question:

Would Ed Gein have killed if his mother were still alive?

Most said no. His crimes weren’t about cruelty; they were about resurrection. He was trying to rebuild the world that had collapsed the moment Augusta died.

One psychiatrist said, “His house was his mind — a landfill of decay surrounding one immaculate shrine.”

Another wrote, “He didn’t want to destroy women. He wanted to become one — the one his mother wished she had.”

The Trial That Never Was

Gein was declared insane. He told investigators about “visiting” graves, about hearing Augusta’s voice guiding his hands. He admitted to killing Mary Hogan and Bernice Worden but claimed he “didn’t remember much.”

In 1958, he was committed to Mendota State Hospital. Doctors diagnosed schizophrenia with severe identity disorder.

He became a model patient: calm, polite, even helpful. He made belts and wallets out of leather — real leather this time — and smiled when nurses spoke kindly to him.

When asked if he missed home, he said softly, “Mother’s waiting there.”

The staff learned not to press further.

The Town That Tried to Forget

Plainfield never recovered. The Gein farm was burned down by an unknown arsonist in 1958. Locals said it was to “cleanse the land.”

For decades afterward, visitors would stop by the cemetery, looking for his mother’s grave, his grave, the graves of his victims. The earth there seemed restless, as if it had learned the habit of being disturbed.

In the end, Ed Gein lived quietly in Mendota until 1984, when he died of respiratory failure at age seventy-seven. The newspapers called him “The Butcher of Plainfield,” “The Ghoul of Wisconsin,” “The Skin Suit Killer.”

But those names missed the essence. He wasn’t a butcher. He wasn’t even a ghoul. He was a void — a man carved out by the woman who gave him life and then took it away piece by piece.

What Remains

The story of Ed Gein is told as horror, but beneath it lies tragedy.

It’s about what happens when love becomes ownership, when faith becomes control, and when fear becomes the only language a child ever learns.

His mother believed she was saving him from the sins of the world. Instead, she made him into proof that sin doesn’t need the world at all — it can bloom perfectly in isolation.

Augusta Gein died thinking she’d raised a saint.

In her image, he built a monster.

The Legend of the Monster

The news broke like a thunderclap.

November 1957: “Cannibal Farm Discovered in Wisconsin.”

The words ran across front pages from New York to Los Angeles. Radio anchors spat them out with disbelief, voices trembling somewhere between disgust and fascination.

The name Ed Gein became a contagion. Within days, journalists, photographers, and thrill-seekers flooded Plainfield — a town of barely seven hundred souls suddenly recast as the capital of evil.

The Nation Looks Into the Mirror

Reporters described everything they saw and much they didn’t. They wrote about “human furniture,” “skin masks,” “rituals in the dark.” The facts alone were unbearable, so they embroidered them until the story gleamed with myth.

But buried under the lurid headlines was a quieter horror: the ordinariness of the man who had done it.

Neighbors remembered a shy handyman who fixed roofs and babysat their kids. He smiled politely, stuttered when nervous, and always said “Yes ma’am.”

That contradiction — the mild voice behind the slaughter — unsettled the American conscience more than the gore itself. If such monstrosity could wear such gentleness, where was the boundary between normal and deranged? Between neighbor and nightmare?

In the atomic 1950s, a decade obsessed with order and conformity, Ed Gein was proof that darkness could live under the neatest white-picket fence.

The Anatomy of a Myth

Hollywood didn’t wait long. In 1960, Alfred Hitchcock released Psycho. Norman Bates — the lonely motel keeper who preserved his dead mother — was Gein reborn on screen, sanitized just enough to pass the censors.

Then came The Texas Chain Saw Massacre in 1974, where the “Leatherface” killer wore masks of human skin.

Silence of the Lambs followed decades later, with Buffalo Bill sewing women’s skin into a suit — a direct echo of Plainfield.

Each retelling stripped away the man and kept the myth: the flesh, the mask, the empty house. America turned him into an archetype — the bogeyman born not in war or politics, but in the domestic womb of the Midwest.

He had become the country’s first folk monster of modern psychology: not a creature from folklore, but from family.

The Science of the Damned

Psychiatrists dissected him the way he once dissected corpses.

They spoke of schizophrenia, psychosexual confusion, severe maternal dominance, identity diffusion.

To them, Gein was not simply insane; he was the logical endpoint of emotional starvation.

One doctor wrote, “He had no father figure, no peers, no outlet. His entire reality was maternal. When she died, the scaffolding of his identity collapsed.”

Another called it “the perfect storm of isolation.”

No community, no friendship, no love — just a single voice repeated until it became the only sound in his head.

To the psychologists, Gein was a specimen.

To theologians, he was a cautionary tale about idolatry — the worship of a person instead of God.

To everyone else, he was something harder to categorize: a reminder that evil can sprout not from hatred, but from devotion gone septic.

The Afterlife of Fear

Decades passed. The Gein farm was ash. The farmhouse no longer stood, but people kept coming anyway. They picked up dirt as souvenirs, took photographs near the empty field, whispered like pilgrims visiting a desecrated shrine.

Fear, once released, doesn’t die; it mutates.

In America’s cultural bloodstream, Ed Gein’s name became shorthand for the kind of horror that hides behind a normal face — the quiet man at the grocery store, the neighbor who keeps to himself, the churchgoer who never misses Sunday.

Every time another killer surfaced — Bundy, Dahmer, Gacy — reporters reached back to Plainfield, tracing the lineage of modern monsters to the man who began it.

But Gein himself, sitting quietly in his hospital cell, never claimed kinship with anyone. He read comic books, listened to the radio, played cards with nurses. When asked if he thought of his mother, he smiled faintly and said,

“Every day. She was a good woman.”

That sentence — calm, sincere, delusional — is perhaps the most terrifying thing he ever said.

The Final Years

At Mendota Mental Health Institute, Gein was a model patient. He mowed the lawn, painted murals, even attended group therapy. The doctors noted his “docile demeanor.” He called them sir and ma’am.

He never raised his voice, never resisted treatment. His hands, once used to dig graves and sew human skin, now folded neatly in his lap.

Visitors sometimes asked what he thought about the films inspired by him. He would tilt his head and say he hadn’t seen them. Then, almost shyly, he’d ask, “Are they scary?”

He died in 1984, age seventy-seven, from respiratory failure.

No family attended the funeral. A handful of staff and reporters came, more out of curiosity than respect. His gravestone, carved with his name, was later stolen by souvenir hunters. Only the dirt remained.

Plainfield finally slept again — though lightly.

The Mother and the Nation

What lingers about Ed Gein is not the gore, not even the mask of flesh. It’s the mirror he held up to American faith and family.

Augusta believed she was saving her son from sin.

She built walls of scripture and shame, thinking she could keep the devil out.

But the devil she feared grew inside those walls — a creature born from silence, obedience, and love so absolute it erased the self.

In her effort to make a saint, she manufactured an emptiness.

When she died, that emptiness reached for flesh to fill the void.

If there is a moral — and perhaps there isn’t — it lies here:

When control replaces compassion, when fear disguises itself as virtue, love can deform into something predatory.

The monster of Plainfield wasn’t found in the cellar. He was raised in the living room, under a crucifix.

What Horror Teaches

Horror endures because it tells the truth through exaggeration.

The story of Ed Gein endures because it barely needs exaggeration at all.

He reminds us that evil isn’t always grand or spectacular. Sometimes it is small, patient, domestic. It sits at the kitchen table, saying grace.

Writers and filmmakers have tried to exorcise his ghost by retelling it — turning real blood into metaphor. But every new adaptation circles back to the same image:

A man alone in a farmhouse, calling out to a dead mother who never answers.

That’s the real horror — not the crimes, but the silence that came before them.

Epilogue

More than seventy years later, Plainfield looks ordinary again. The corn grows tall, the snow still falls heavy in winter, and the cemetery where Augusta lies is quiet. Visitors leave pennies on her grave, maybe for luck, maybe for penance.

Ed Gein’s story has become folklore, stripped of pity, reduced to shorthand for madness. Yet beneath the myth, a human tragedy remains: a warning written in flesh and frost.

It is the story of a woman who mistook fear for faith.

And of a boy who mistook obedience for love.

Together, they built a house that smelled of devotion and rot.

When it finally collapsed, America walked through its ruins — and never looked at the word mother the same way again.

News

The Face Hidden in Every Frame: The Jennifer Kesse Mystery

The Morning That Changed Everything A Life Built with Purpose The January sun rose over Orlando, Florida, painting the sky…

“What Really Happened to the Springfield Three? Inside America’s Greatest Unsolved Mystery”

The Last Normal Night The summer air hung thick and sweet over Springfield, Missouri, on the evening of June 6,…

After 46 Years, DNA Finally Whispered His Name: The Carla Walker Murder That Refused to Stay Cold

A Valentine’s Dance, A Stolen Life, and Nearly Half a Century of Waiting for Justice February 17, 1974, started like any other Sunday…

After 46 Years, DNA Finally Whispered His Name: The Carla Walker Murder That Refused to Stay Cold

A Valentine’s Dance, A Stolen Life, and Nearly Half a Century of Waiting for Justice February 17, 1974, started like any other Sunday…

The Hart Family Tragedy: The Perfect Instagram Family That Hid a Decade of Horror Before Driving Off a Cliff

When “Free Hugs” Became a Funeral Shroud: The Untold Story America Needs to Hear On March 26, 2018, a German…

“Kidnapped in Cleveland: The True Story of Three Women Who Refused to Give Up Hope After a Decade in Hell”

The morning of August 23, 2002, started like any other desperate morning in Michelle Knight’s life. She stood in…

End of content

No more pages to load