The Final Glimpse

September 10, 1996. Courtroom 108 in the Van Nuys Superior Court building. The fluorescent lights hummed overhead as two young men in prison jumpsuits sat side by side at the defense table, their hands shackled, their futures about to be sealed.

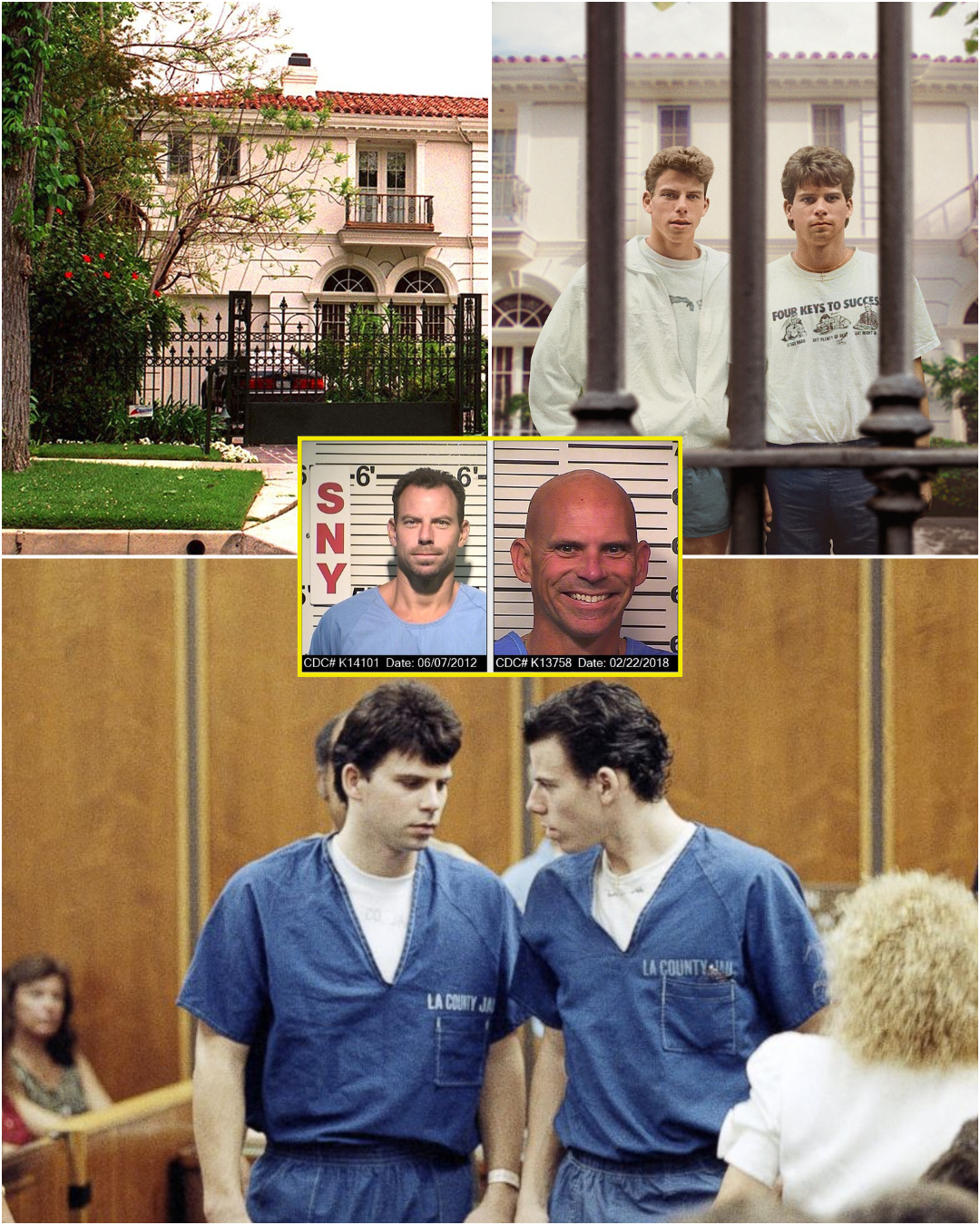

Lyle Menendez, 28 years old, stared straight ahead with the same expressionless face he’d worn throughout most of the trial. Erik Menendez, 25, occasionally glanced at his older brother, the only person in the world who truly understood what they’d been through—both the abuse they’d suffered and the horrific act they’d committed together.

The jury had spoken. Guilty on two counts of first-degree murder. No chance of parole. Life in prison.

As bailiffs prepared to lead them away to begin their sentences, the brothers shared what they thought might be a final goodbye. They hugged briefly. Lyle whispered something in Erik’s ear. Erik nodded, tears streaming down his face.

They had no way of knowing that this would be the last time they would see each other’s faces, touch each other, speak to each other in person for 7,996 days.

Twenty-two years. Nearly a quarter century. Longer than Erik had been alive when they killed their parents.

The criminal justice system was about to inflict a punishment that neither judge nor jury had explicitly ordered: the complete and total separation of two brothers whose bond—forged in shared trauma, twisted by unspeakable abuse, and cemented in blood—was the only thing that had kept them alive.

This is the story nobody talks about when they discuss the Menendez brothers. Not the murders. Not the trials. Not even the abuse.

This is the story of what happened after the cameras stopped rolling. When the media moved on. When America forgot about Lyle and Erik Menendez.

This is the story of 22 years in the dark.

The Dead of Night

The separation happened without warning.

In the immediate aftermath of their sentencing, Lyle and Erik were both housed at the Los Angeles County Jail while authorities decided where to send them permanently. They were in different units but could occasionally see each other during transfers, catch glimpses in hallways, exchange brief words when guards weren’t paying attention.

It wasn’t much. But it was something.

Then, one night in early 1997—Lyle later described it as happening “in the dead of night”—guards came for him.

No explanation. No goodbye. No final conversation with his younger brother.

Lyle was shackled, loaded into a transport van, and driven north to Mule Creek State Prison near Sacramento—more than 400 miles from where Erik remained in Southern California. By the time Erik woke up the next morning, Lyle was gone.

“It was hugely traumatizing,” Lyle would later tell DailyMailTV in 2018. “We just always knew that one of the things we wanted to do was try to be reunited. I don’t know that I really ever recovered from that. It’s like a healing of a wound to be reunited.”

The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation had a policy at the time: inmates convicted of the same crime—particularly high-profile family annihilators—were to be separated to prevent them from conspiring, communicating, or forming alliances that might disrupt prison order.

It was a bureaucratic decision, made by administrators who saw only case numbers and security protocols. They didn’t see two brothers who had been each other’s only source of protection during years of sexual abuse. They didn’t see the complex psychological codependency that had formed when Jose Menendez raped Erik while Lyle listened through the walls, powerless to stop it. They didn’t see the shared guilt, the shared trauma, the shared humanity of two men who had committed an unforgivable act together and would now spend the rest of their lives paying for it—separately.

Letters in the Dark

For the first few months after separation, both brothers struggled to adjust. Erik was eventually transferred to Pleasant Valley State Prison in Coalinga, California—still in the southern part of the state but isolated, rural, and one of the more dangerous facilities in the system.

They couldn’t see each other. They couldn’t touch. They couldn’t have face-to-face conversations.

But they could write letters.

And so they did. Constantly. Obsessively. The letters became their lifeline—the only tangible proof that the other brother was still alive, still thinking of them, still holding onto the bond that had defined both their childhoods and their crimes.

Lyle’s letters were often practical. He’d write about his daily routine, about books he was reading, about legal strategies for appeals. He took on the role he’d always had—the older brother, the protector, the one trying to fix things even when they couldn’t be fixed.

Erik’s letters were more emotional. He wrote about nightmares—not just about their parents or the murders, but about losing Lyle. He wrote about feeling utterly alone in a way he hadn’t felt even during the worst days of their father’s abuse. At least then, he’d had Lyle nearby. Now he had nothing except words on paper that took days to arrive and could be read by guards at any time.

The prison system allowed them to exchange letters, but there were restrictions. Content was monitored. Anything deemed “conspiratorial” or inappropriate would be confiscated. They learned to write carefully, to say what needed to be said without saying too much.

In those letters, they reminded each other why they’d done it. They reinforced the narrative of abuse, of fear, of two young men who’d truly believed their parents were going to kill them to keep the secret of Jose’s sexual violence from ever getting out.

They reminded each other that they weren’t monsters. That they were brothers. That they loved each other.

And they promised that somehow, someday, they would see each other again.

Phone Calls from Hell

In addition to letters, the brothers were allowed periodic phone calls. These were rare, expensive, and heavily monitored. Every word was recorded. Every conversation could be replayed, analyzed, used against them if they said something incriminating during ongoing appeals.

But they called anyway.

Journalist Robert Rand, who has covered the Menendez case since 1989 and maintains relationships with both brothers, described these phone calls as “heartbreaking.”

“They would spend the first few minutes just saying each other’s names,” Rand said. “Just hearing the other’s voice was emotional enough that sometimes they couldn’t even speak. You have to understand—these are two men who had been through the most intimate trauma together, who had killed together, who had faced trial and conviction together. And now they’re in separate prisons, unable to touch, unable to see each other’s faces. The phone calls were all they had.”

During these calls, they’d catch up on prison life. Erik would tell Lyle about educational programs he was enrolled in, about how he was trying to better himself despite the life sentence. Lyle would talk about his work in prison, about the other inmates, about small victories like getting access to better books or winning an appeal on some minor procedural issue.

They didn’t talk much about the murders. There was nothing left to say about that. The past was fixed. The future was bleak.

But they talked about each other. About memories from before—before the abuse got unbearable, before everything fell apart, before the night in August 1989 when they loaded shotguns and waited for their parents to come home.

They talked about being kids. About playing together. About the moments when they’d been happy.

And they talked about hope. The dwindling, desperate hope that maybe—somehow—they would be in the same place again.

The Parallel Lives

As the years turned into decades, Lyle and Erik each built separate lives within the prison system. They adapted. They survived. But they never stopped missing each other.

Lyle at Mule Creek State Prison:

Lyle, always the more outgoing and charismatic of the two brothers, threw himself into prison programs. He became a model prisoner—no infractions, no violence, no trouble. He took college courses through correspondence programs. He mentored younger inmates. He worked in prison administrative roles.

In 2003, he married Rebecca Sneed, a magazine editor who had begun corresponding with him years earlier. The wedding was held in the prison, with no physical contact allowed. It was a strange, sterile ceremony—a marriage in name only, with no possibility of intimacy, children, or a future together outside prison walls.

But it gave Lyle something: companionship. Someone besides Erik who cared whether he lived or died.

Still, every night when he lay in his cell, he thought about Erik. Wondered if his younger brother was okay. Worried about whether Erik was being harassed by other inmates, whether he was slipping into depression, whether he was holding on.

Erik at Pleasant Valley State Prison:

Erik’s path was quieter, more internal. He struggled more openly with depression and anxiety. The nightmares that had plagued him since childhood—nightmares of his father’s abuse—intensified in prison. He underwent therapy, took medication, tried to make sense of a life that had gone so horrifically wrong.

In 1999, he married Tammi Saccoman, a woman who had seen him on television during the trials and felt compelled to reach out. Like Lyle’s marriage, Erik’s was conducted entirely through letters, phone calls, and monitored prison visits. There was no physical intimacy, no shared life beyond the prison walls.

But Tammi became Erik’s advocate. She fought for him, spoke on his behalf, tried to keep his case in the public eye even as America moved on to other scandals and other trials.

And every day, Erik woke up thinking about Lyle. Missing his older brother. Feeling incomplete without the one person who truly understood what they’d been through.

The Campaigns That Failed

Over the years, both brothers—along with their attorneys, family members, and supporters—launched repeated campaigns to be housed together. They filed petitions. They cited studies showing that familial connections reduce recidivism and improve mental health outcomes in long-term prisoners. They argued that neither had committed any infractions and both had been model prisoners for years.

Every request was denied.

The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation maintained its position: inmates convicted of the same crime should be separated. The policy was designed to prevent collusion, to avoid the formation of powerful inmate alliances, to maintain security and order.

But to Lyle and Erik, it felt like cruelty for its own sake. They’d already been convicted. They were already serving life without parole. What could they possibly conspire to do? They weren’t going to escape. They weren’t going to harm anyone. They just wanted to be able to see each other, to talk without the mediation of monitored phone lines and censored letters.

The system said no.

And so the years continued to pass. 2000. 2005. 2010. 2015.

Two brothers, both alive, both in the same state, separated by a few hundred miles and an unbending bureaucratic policy.

The Policy Change

In 2013, something shifted.

The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation quietly changed its policy regarding family members serving time in the prison system. New research had shown that allowing familial connections actually improved prisoner behavior and mental health. Separated family members became depressed, aggressive, and harder to manage. United family members—when both were well-behaved—tended to stabilize each other.

Erik was transferred that year to R.J. Donovan Correctional Facility in San Diego. It was a move that seemed random at first—just another administrative shuffle.

But then, in early 2018, something extraordinary happened.

Lyle Menendez was transferred to R.J. Donovan Correctional Facility. The same prison where Erik had been for five years.

After 22 years, the brothers were in the same facility.

But even then, the system made them wait. Lyle arrived in February 2018. He was housed in a different unit from Erik. They knew the other was nearby—just buildings away—but they still couldn’t see each other. Prison officials needed to assess, to process, to ensure that housing them together wouldn’t create security issues.

For two more months, they waited. So close. Yet still separated.

April 4, 2018 – The Reunion

On April 4, 2018, prison officials finally allowed Lyle and Erik Menendez to see each other for the first time in 7,996 days.

Lyle described having to “walk a long way” to the area where Erik was being brought. His heart was pounding. He’d waited so long for this moment that part of him couldn’t believe it was actually happening.

He saw the van pull up. He saw Erik step out, shackled, escorted by guards.

And then their eyes met.

“I burst into tears,” Lyle said later. “I wasn’t sure how I would react…I just felt a lot of adrenaline and just, I ended up bursting into tears, which is quite an emotional moment.”

The brothers were allowed to approach each other. They embraced—fully, deeply, desperately.

Robert Rand, the journalist who had covered their case for nearly 30 years, described the reunion as “deeply emotional.” He said the brothers “embraced for several minutes without saying a word.” Prison guards, who had seen countless inmate reunions over the years, were reportedly moved by the scene.

They let the brothers have an hour together. Just the two of them, in a supervised area, with guards nearby but giving them as much privacy as the situation allowed.

What did they talk about in that hour? Neither brother has said publicly. But it’s not hard to imagine.

“I love you.”

“I missed you.”

“I thought I’d never see you again.”

“We’re together now.”

“Finally. Finally.”

Life Together, Still Behind Bars

Since that reunion in April 2018, Lyle and Erik Menendez have been housed in the same facility. They don’t share a cell—prison regulations don’t allow that—but they live in the same housing unit known as “Echo Yard,” a section of R.J. Donovan Correctional Facility reserved for well-behaved inmates who’ve demonstrated years of good conduct.

Echo Yard offers privileges that other areas of the prison don’t. Educational opportunities. Art and yoga classes. Rehabilitative programs addressing anger management and substance abuse. Phone calls and video calls on tablets.

Most importantly: Lyle and Erik see each other every day in the prison yard.

After 22 years of separation, they can finally have normal conversations. They can sit together. They can see each other’s faces, watch each other age, be present in each other’s lives in ways that letters and phone calls could never replicate.

“It’s been a healing of a wound,” Lyle said. “To be reunited.”

For Erik, who had struggled more visibly with depression during the separation, the reunion has been transformative. Friends and advocates who visit him say he seems lighter, more hopeful, more engaged with life despite the circumstances.

The brothers are now 57 (Lyle) and 54 (Erik) years old. They’ve spent more than half their lives in prison. They will likely die in prison, given their life-without-parole sentences.

But at least they’ll die together.

The Cruel Math of Justice

The 22-year separation of Lyle and Erik Menendez raises uncomfortable questions about the American criminal justice system and what we’re trying to accomplish when we punish people.

Both brothers were convicted of murdering their parents. Both were sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole. That was the punishment: loss of freedom for the rest of their natural lives.

But the separation was an additional punishment—one that was never ordered by a judge, never argued for by prosecutors, never intended by the jury. It was a bureaucratic decision made in the name of security and order.

Was it necessary? Did it accomplish anything beyond inflicting additional psychological torment on two men who were already serving the harshest possible sentence?

The brothers have said repeatedly that the separation was, in some ways, worse than the abuse they’d suffered as children. At least during the abuse, they’d had each other. In prison, separated, they had nothing.

“I don’t know that I really ever recovered from that,” Lyle said of the separation.

And here’s the thing that makes this story so complicated, so morally murky: Lyle and Erik Menendez did kill their parents. They shot Jose and Kitty Menendez at close range with shotguns, then reloaded and continued shooting. It was brutal. It was premeditated. It was, by any definition, murder.

But they were also victims. The abuse they suffered—decades of sexual violence, psychological manipulation, and terror—was real. Multiple family members testified to it. A letter Erik wrote to his cousin eight months before the murders described the ongoing abuse. A former member of the boy band Menudo came forward decades later to say that Jose Menendez had raped him too.

So what do we owe people like Lyle and Erik Menendez? Punishment, certainly. Justice for their victims, absolutely.

But do we also owe them basic humanity? Do we owe them the right to maintain the one healthy relationship they have—with each other?

The criminal justice system said no for 22 years.

And then, quietly, it changed its mind.

2024-2025 – The Fight for Freedom

As of 2025, Lyle and Erik Menendez are no longer fighting just to be together. They’re fighting to be free.

In 2023, their attorneys filed a habeas corpus petition presenting two significant pieces of new evidence that weren’t available during their 1996 trial:

Roy Rosselló’s testimony: The former Menudo member came forward in the 2023 Peacock documentary “Menendez + Menudo: Boys Betrayed” to say that Jose Menendez raped him in the early 1980s when he was 14 or 15 years old. This corroborates the brothers’ claims that their father was a serial sexual predator.

Erik’s letter to Andy Cano: A letter Erik wrote to his cousin in December 1988—eight months before the murders—describing ongoing sexual abuse by his father. The letter was “lost” for decades and only recently resurfaced.

These pieces of evidence, the defense argues, would have changed the outcome of the trial if the jury had seen them. They provide independent corroboration of the abuse the brothers described.

In September 2025, a judge denied their petition for a new trial, saying the evidence wasn’t strong enough.

But in May 2025, another judge resentenced them from life without parole to 50 years to life—making them technically eligible for parole immediately, since they’ve already served 35 years.

A parole hearing was scheduled for August 2025. The final decision rests with the California parole board and, ultimately, the governor.

Public opinion has shifted dramatically since the 1990s. Back then, male victims of sexual abuse were rarely believed. The idea that a wealthy father could be a monster was dismissed as implausible. The brutality of the murders overshadowed any sympathy for the brothers.

But in 2025, we understand trauma differently. We believe male victims. We recognize that abuse victims can also be perpetrators. We understand that people can be both guilty and sympathetic, both criminals and victims.

Twenty-plus family members—including José and Kitty’s siblings—are now publicly supporting the brothers’ release, saying they’ve suffered enough and deserve a chance at freedom.

Roy Rosselló, the Menudo singer whose testimony helped reopen the case, said in 2025: “I am proud and happy about the judge’s decision. My testimony was not in vain. To my understanding, these individuals are always innocent victims. Their souls have been lost, condemned, and mutilated, devoid of hope, future, or destiny since the day their father began to abuse them.”

Whether Lyle and Erik will actually walk free remains to be seen. But one thing is certain: if they are released, they will walk out together.

After 35 years in prison—22 of them separated, unable to see each other’s faces—they will finally have the freedom to be brothers again.

Not in a prison yard. Not through letters and phone calls.

But in the world. Together.

The Bond That Couldn’t Be Broken

The story of Lyle and Erik Menendez is, at its core, a story about bonds.

The bond between a father and his sons—twisted into something monstrous through years of sexual abuse.

The bond between two brothers—forged in shared trauma, tested by unimaginable pressure, and ultimately strong enough to survive 22 years of forced separation.

The bond between victim and perpetrator—because Lyle and Erik are both, and understanding their story requires holding both truths simultaneously.

When they embraced on April 4, 2018, after 7,996 days apart, they were embracing not just each other but their shared past, their shared guilt, their shared trauma, and their shared hope that somehow, despite everything, they could find a way to live with what they’d done.

“It was just a remarkable moment,” Lyle said.

Remarkable. After everything—the abuse, the murders, the trials, the life sentences, the decades in separate prisons—the thing Lyle Menendez chose to describe their reunion was: remarkable.

Not tragic. Not bitter. Not hopeless.

Remarkable.

Because after 22 years of darkness, they finally had light.

They had each other again.

And for two brothers who killed their parents because they believed it was the only way to survive, that reunion was perhaps the closest thing to redemption they’ll ever know.

The American criminal justice system tried to keep them apart for two decades. It failed.

Because some bonds—even bonds forged in blood and trauma—are simply too strong to break.

News

The Face Hidden in Every Frame: The Jennifer Kesse Mystery

The Morning That Changed Everything A Life Built with Purpose The January sun rose over Orlando, Florida, painting the sky…

“What Really Happened to the Springfield Three? Inside America’s Greatest Unsolved Mystery”

The Last Normal Night The summer air hung thick and sweet over Springfield, Missouri, on the evening of June 6,…

After 46 Years, DNA Finally Whispered His Name: The Carla Walker Murder That Refused to Stay Cold

A Valentine’s Dance, A Stolen Life, and Nearly Half a Century of Waiting for Justice February 17, 1974, started like any other Sunday…

After 46 Years, DNA Finally Whispered His Name: The Carla Walker Murder That Refused to Stay Cold

A Valentine’s Dance, A Stolen Life, and Nearly Half a Century of Waiting for Justice February 17, 1974, started like any other Sunday…

The Hart Family Tragedy: The Perfect Instagram Family That Hid a Decade of Horror Before Driving Off a Cliff

When “Free Hugs” Became a Funeral Shroud: The Untold Story America Needs to Hear On March 26, 2018, a German…

“Kidnapped in Cleveland: The True Story of Three Women Who Refused to Give Up Hope After a Decade in Hell”

The morning of August 23, 2002, started like any other desperate morning in Michelle Knight’s life. She stood in…

End of content

No more pages to load