On a frigid February morning in 2010, Ontario Provincial Police Detective Sergeant Jim Smyth sat down across from one of Canada’s most decorated military officers. The man facing him wore casual civilian clothes, his posture relaxed, a piece of gum working methodically in his jaw. Colonel Russell Williams smiled easily, even told the detective to “call me Russ, please”.

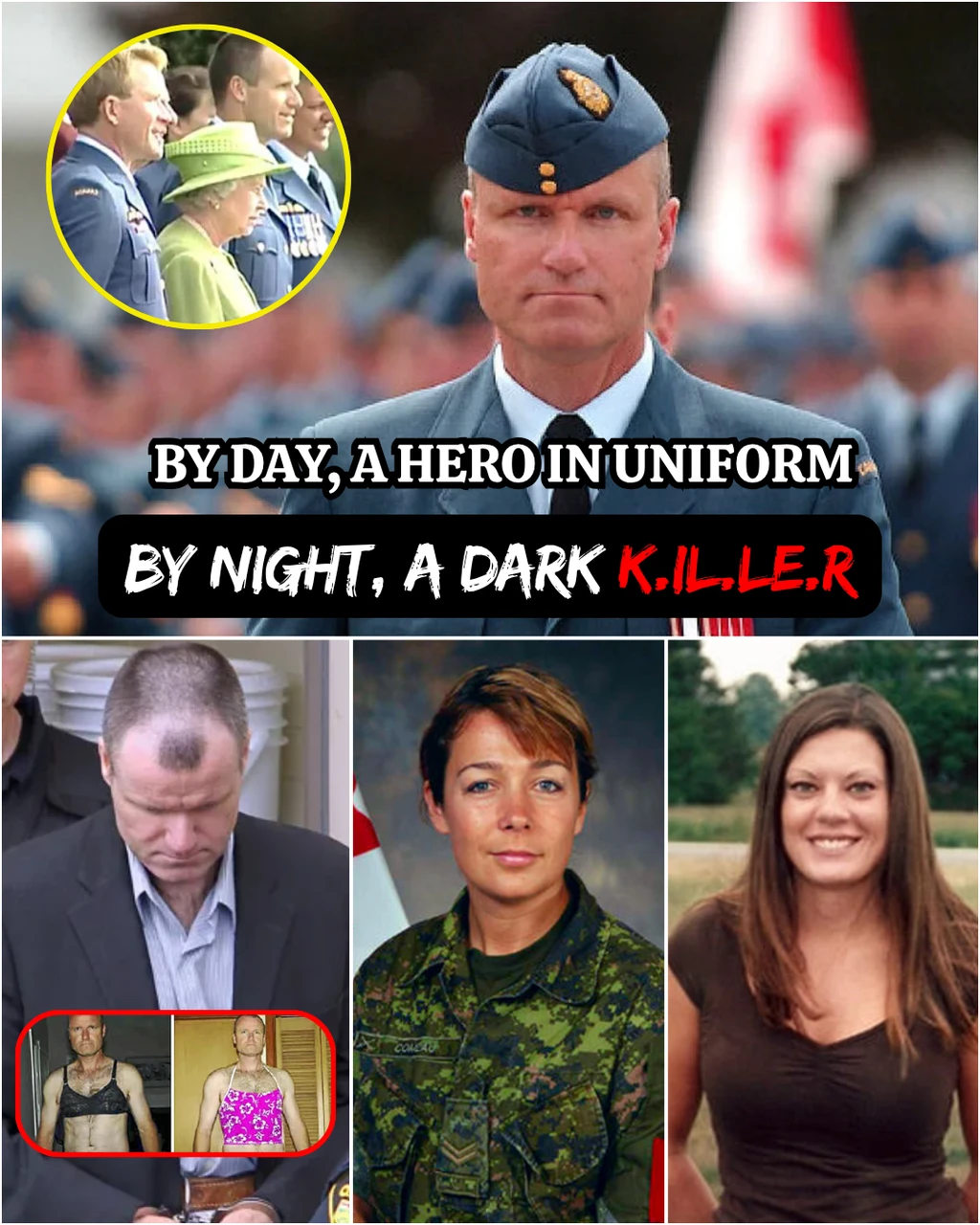

To anyone watching through the two-way mirror, Williams appeared utterly at ease—the picture of cooperation, the epitome of a respectable citizen with nothing to hide. After all, this was a man who had piloted Queen Elizabeth II across Canadian skies, who commanded the nation’s largest air force base, who had dedicated more than two decades to serving his country with distinction.

What no one in that room could have imagined—what would emerge over the next ten excruciating hours—was that the decorated colonel sitting before them had been living an unthinkable double life. By day, he was Commander Williams, respected leader of Canadian Forces Base Trenton. By night, he had transformed into something far more sinister: a prowler, a predator, and ultimately, a cold-blooded killer.

This is the story of how one man’s descent into darkness went undetected for years, hidden behind a uniform adorned with medals and a reputation beyond reproach.

The Perfect Life

Russell Williams seemed to have it all. Born in Bromsgrove, England in 1963, he immigrated to Canada with his family as a child. Though his parents divorced when he was just six years old, Williams pushed forward, excelling academically and earning admission to the prestigious University of Toronto Scarborough, where he studied economics and political science.

In 1987, at age 24, Williams joined the Canadian Armed Forces with dreams of serving his country. He quickly distinguished himself as an exceptional pilot, earning coveted positions that placed him in the cockpit of VIP aircraft. His responsibilities included flying some of the most important figures in Canadian politics and international diplomacy—prime ministers, governors general, and even British royalty.

By 2009, Williams had reached the pinnacle of his military career: command of CFB Trenton, the nerve center of Canada’s air transport operations and the country’s largest military airbase. At 46 years old, he was living what most would consider the American—or in this case, Canadian—dream.

He had married Mary Elizabeth Harriman, a successful executive director of the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. Together, they owned a spacious home in Ottawa, the nation’s capital, and had purchased a cozy cottage as a weekend retreat in Tweed, a small town about two and a half hours away. To their neighbors, they were the ideal couple—accomplished, affluent, and admired.

But the cottage in Tweed would become ground zero for Williams’ transformation from decorated officer to depraved criminal.

The First Trespass

What began as a seemingly innocuous compulsion in 2007 would eventually spiral into unspeakable horror. Williams started breaking into homes in neighborhoods near his cottage, carefully selecting targets when residents were away. His objective was bizarre yet specific: stealing women’s and girls’ underwear.

The first known victim was just 12 years old. While the family was out, Williams broke into their home, found the child’s pink underwear, and masturbated with it. But he didn’t stop there. In a disturbing ritual that would become his signature, Williams photographed and videotaped himself wearing the stolen garments, posing in front of mirrors for hours.

He was meticulous, almost obsessive in his caution. Williams understood that he had everything to lose—his career, his reputation, his freedom. So he took extreme care not to leave evidence behind, cleaning up after himself and slipping away undetected.

Over the next two years, Williams’ compulsion intensified. He broke into home after home—ultimately 82 different residences. Some he visited multiple times, returning like a phantom to steal more items and indulge his fetish. He kept detailed records of every break-in: dates, times, victims’ names, items stolen. It was a catalog of crimes, hidden in plain sight on his personal computer.

The stolen underwear accumulated in his home, carefully stored and categorized. He photographed himself in each piece, creating a grotesque archive of his transgressions. Yet despite this escalating pattern of criminal behavior, Williams maintained his professional façade flawlessly. By day, he commanded respect and trust. By night, he prowled like a predator.

Escalation into Violence

In September 2009, Williams crossed a terrifying threshold. Breaking and entering was no longer enough to satisfy whatever dark urge drove him. He began targeting women not just for their belongings, but for something far more sinister—their bodies.

The first known sexual assault occurred in Tweed, where a woman was attacked in her own home. Williams had waited in the darkness for her to return, then ambushed her, binding her to a chair with rope and duct tape. He photographed her during the assault, just as he had photographed himself with the stolen underwear. The woman survived, traumatized but alive.

Just two weeks later, Williams struck again. Another woman in the same area was assaulted in her home in an almost identical fashion—bound, photographed, violated. The attacks followed a disturbing pattern that suggested careful planning and a complete lack of remorse.

The small community of Tweed was gripped by fear. Police increased patrols, but they had few leads. One of the assault victims believed her attacker might be a neighbor named Larry Jones, and suspicion fell heavily on the innocent man. He was ostracized, harassed, and verbally attacked by frightened neighbors convinced they knew the identity of the predator in their midst.

They were wrong. The real perpetrator was someone they would never have suspected—someone who wore a uniform, who commanded an air force base, who was supposed to protect them.

Meanwhile, Russell Williams was preparing to commit his most heinous acts yet.

Marie-France Comeau

On November 24, 2009, Williams set his sights on a new target: 38-year-old Corporal Marie-France Comeau. She wasn’t a stranger. In fact, Williams knew her professionally—Comeau served under his command at CFB Trenton, working as a flight attendant on the same VIP aircraft that Williams piloted.

As her commanding officer, Williams had access to Comeau’s personnel file, her work schedule, her home address. He had met her on multiple flights, knew she lived alone, and used his position of authority to gather every detail he needed to plan his attack.

That November night, Williams broke into Comeau’s home and waited. When she arrived, he ambushed her, striking her head with a flashlight and quickly overpowering her. He bound her with duct tape and rope, then spent the next three hours brutally assaulting her while documenting everything with his video camera.

Comeau pleaded for her life. According to court documents later revealed during Williams’ trial, she cried out: “You’re going to kill me, aren’t you? I don’t want to die. I don’t deserve to die. I have been good”.

Her pleas fell on deaf ears. Williams coldly covered her mouth and nose with duct tape, suffocating her. He photographed her body twice after death, collected several items of her underwear as trophies, and left.

Then, in an act of staggering callousness that would later shock the nation, Williams attended Comeau’s funeral. In his capacity as base commander, he even sent a letter of condolence to her father, a military veteran, expressing his sympathies for the family’s loss.

No one suspected him. How could they? He was Colonel Williams—decorated pilot, trusted commander, pillar of the military community.

But Williams wasn’t finished. Two months later, he would kill again.

Jessica Lloyd

Twenty-seven-year-old Jessica Lloyd had her whole life ahead of her. She worked for Tri-Board Student Transportation Services in Napanee, Ontario, coordinating school bus routes and administrative tasks. Known throughout the Quinte region as witty, social, and easy to get along with, Jessica had friends in numerous circles and was deeply loved by her family.

She lived alone in a modest home on Highway 37, near the small town of Belleville—just minutes from Russell Williams’ cottage in Tweed.

On the evening of January 28, 2010, Jessica was at home, exercising on her treadmill in the basement. She had no idea that someone was watching her from outside, waiting for the right moment. She had no idea that this would be her last night alive.

Around 1:00 a.m. on January 29, Williams broke into her home. He had been stalking her, learning her routines, planning his attack. When Jessica finally went to bed, Williams was already inside.

He struck her hard with a flashlight, binding her with duct tape as she regained consciousness. For the next three hours, he sexually assaulted her while videotaping everything—a grotesque ritual he had perfected with his previous victims. Jessica begged for her life, pleading with her attacker to spare her.

But Williams had made a decision. He couldn’t risk leaving her alive to identify him. Instead of releasing her, he forced Jessica into his Nissan Pathfinder and drove her back to his cottage in Tweed, about 30 minutes away.

Over the next 21 hours, Williams kept Jessica prisoner in his home. He sexually assaulted her repeatedly, photographed her, and coldly documented his crimes. According to his later confession, Jessica continued to beg for her life throughout the ordeal, promising she wouldn’t tell anyone if he would just let her go.

Williams made a show of agreeing, but he had already decided her fate. On the evening of January 29, he strangled Jessica Lloyd to death. He hid her body in his garage, waiting for an opportunity to dispose of it when suspicion had died down.

The Search

When Jessica failed to show up for work on January 29, her employer became concerned. They tried calling her repeatedly—no answer. They contacted her brother, Andy Lloyd, who immediately sensed something was terribly wrong.

Andy rushed to Jessica’s home. The door was unlocked, unusual for his cautious sister. Inside, the house was in disarray—clear signs of a struggle. Her glasses and wallet had been dropped on the driveway leading to the garage, as if torn from her during a violent confrontation.

Jessica’s family reported her missing immediately. Within hours, a massive search operation was underway. Family members, friends, and first responders combed the area, distributing missing person posters and conducting organized searches throughout Belleville and the surrounding communities.

“We had posters and search parties for over a week,” Andy Lloyd later recalled. “Definitely as the days went on, they were looking for tire tracks. It seems like something out of a CSI episode. It just doesn’t seem like that’s the reality in a small community, the house that I grew up in”.

The Ontario Provincial Police arrived at the scene and immediately noticed something crucial: distinctive tire tracks in the snow along the north tree line of Jessica’s property, approximately 100 meters from her home. The tracks had frozen in the frigid Canadian winter, preserving them perfectly.

These weren’t ordinary tire treads. They were unusual, specific—the kind of pattern that might help investigators identify a particular vehicle.

Police also found boot prints near a fire pit in Jessica’s backyard. The size, pattern, and depth suggested a man of considerable height and weight.

As the days passed with no sign of Jessica, her family’s hope began to fade. The community rallied, but fear was spreading through the small towns of Belleville and Tweed. Two women had already been sexually assaulted in their homes just months earlier. Corporal Comeau had been murdered in November. Now Jessica Lloyd had vanished.

Was there a serial predator hunting women in their quiet communities?

The Roadblock

On February 4, 2010—one week after Jessica’s disappearance—the OPP implemented an aggressive strategy. They set up a roadblock on Highway 37 near Belleville, the main route through the area. For 11 hours, from 7:00 p.m. that evening until 6:00 a.m. the next morning, officers stopped every vehicle that passed through, examining tire treads and questioning drivers.

It was a massive undertaking, but investigators were desperate. Time was running out.

That evening, Russell Williams needed to drive from his Ottawa home back to his cottage in Tweed. Normally, he drove his BMW sedan. But on this particular night—perhaps trying to avoid drawing attention, or perhaps simply by chance—Williams was driving his Nissan Pathfinder SUV.

The SUV with the distinctive tires.

When Williams pulled up to the roadblock, an officer immediately noticed the unusual tread pattern on the Pathfinder’s tires. They looked identical to the tracks photographed at Jessica Lloyd’s home.

But there was a problem: the man driving this vehicle was Colonel Russell Williams, commander of CFB Trenton—one of the most respected military officers in the region. He was calm, cooperative, and seemed eager to help with the investigation.

When asked if they could examine his vehicle more closely, Williams told the officers he was in a hurry—his son was ill and he needed to get home quickly. The officers, deferential to his rank and position, allowed him to pass through the checkpoint.

But something didn’t sit right. After Williams drove away, the officers reviewed their notes and cross-referenced information from Williams’ personnel file.

Russell Williams didn’t have a son. He had lied.

The Interrogation

On Sunday, February 7, 2010, at 3:00 p.m., Russell Williams walked into OPP headquarters in Ottawa, believing he was simply being asked to answer a few follow-up questions. He wasn’t under arrest. He had voluntarily agreed to come in.

Waiting for him was Detective Staff Sergeant Jim Smyth, one of Canada’s most skilled interrogators, a behavioral specialist trained in the Reid Technique—a method of psychological interrogation designed to elicit confessions through building rapport and gradually increasing pressure.

Smyth was polite, almost deferential. He offered Williams water, thanked him for coming in, and treated him with the respect befitting a colonel. Williams seemed relaxed, chewing gum, legs crossed casually. When Smyth addressed him as “Colonel Williams,” the officer smiled and said, “Call me Russ, please”.

For the first few hours, Smyth asked gentle questions about Williams’ routine, his work schedule, his vehicles. Williams answered easily, offering details, even volunteering information. When Smyth mentioned Jessica Lloyd’s disappearance, Williams expressed concern and sympathy.

“I didn’t even know her name till I heard about it on the news,” Williams said.

But Smyth was patient. He slowly began introducing evidence. The tire tracks found at Jessica’s home. The distinctive tread pattern. The fact that Williams had been stopped at the roadblock driving a vehicle with matching tires.

Williams’ demeanor shifted slightly. The gum chewing slowed. His responses became shorter, more guarded.

Then Smyth placed two photographs on the table: a boot print found near Jessica Lloyd’s home, and a photocopy of the sole of the boot Williams was wearing at that very moment.

“These are identical,” Smyth said calmly.

Williams stared at the images, silent. For nearly five minutes, he said nothing—an agonizing stretch that Smyth did not interrupt.

“You and I both know that you were at Jessica Lloyd’s house,” Smyth continued quietly. “And I need to know why”.

Williams pulled the photos closer, examining them. “Well,” he finally said, “I don’t know what to say”.

Smyth leaned forward. “You need to explain it”.

For the next hour, Williams clung desperately to denial. But Smyth was relentless, presenting more evidence piece by piece. The tire tracks. The boot prints. The timeline that placed Williams in the area when Jessica disappeared.

Then Smyth delivered the psychological blow that would break Williams’ resolve. He told Williams that at that very moment, police officers were executing search warrants at both his homes—the Ottawa residence where his wife lived, and the cottage in Tweed.

“They’re going through your wife’s dream home right now,” Smyth said. “Tearing it apart, room by room”.

Williams’ face crumbled. The one thing he had desperately wanted to protect—his wife, her reputation, her life—was already being destroyed. There was no point in continuing the charade.

At 7:45 p.m.—four hours and 45 minutes into the interrogation—Williams began to confess.

“Call Me Russ”

What followed was ten hours of chilling revelations. Williams methodically described his crimes in disturbing detail—82 break-ins, dozens of thefts of women’s underwear, two sexual assaults, and two murders.

He told Smyth about following Jessica Lloyd, watching her exercise in her basement, waiting for her to go to sleep. He described striking her with a flashlight, binding her, assaulting her for hours. He admitted to driving her back to his cottage, holding her prisoner for 21 hours, and ultimately strangling her to death.

When Smyth asked about Corporal Comeau, Williams initially claimed he had only met her once and couldn’t remember much about her. But when pressed, he confessed to that murder as well—the brutal attack in her home, the suffocation, the cold disposal of evidence.

Most disturbingly, Williams revealed the location of Jessica Lloyd’s body. He drew a map showing where he had dumped her in a wooded area off Cary Road near Tweed. Police were dispatched immediately, and early the next morning—February 8, 2010—they found Jessica’s remains exactly where Williams said they would be.

The Lloyd family was watching the Super Bowl when they received the devastating news.

As the interrogation continued through the night, Williams also directed police to evidence hidden throughout his homes: thousands of photographs of himself wearing stolen underwear, videos of his assaults on victims, detailed logs documenting every crime, and trophies taken from each break-in—87 pieces of underwear belonging to young girls and women.

By the time Williams finished confessing, the sun was rising on February 8. He had been in that interrogation room for ten hours. He had admitted to crimes that shocked even seasoned investigators.

Detective Smyth, maintaining his professional composure throughout, finally placed Williams under arrest.

The decorated colonel—the man who had flown the Queen, who had commanded Canada’s largest air base, who had been trusted with national security—was now a confessed serial sexual predator and killer.

The Courtroom

On October 18, 2010, Russell Williams stood before Justice Robert Scott at the Ontario Superior Court in Belleville. The courtroom was packed with journalists, victims’ family members, community members, and military personnel who still couldn’t believe what had happened.

Williams pleaded guilty to all charges: two counts of first-degree murder, two counts of sexual assault, and 82 counts of burglary and breaking and entering. There would be no trial, no prolonged legal battle. He had confessed to everything.

What followed over the next four days was a sentencing hearing unlike anything Canada had witnessed before. The Crown prosecutor, Lee Burgess, methodically presented evidence that revealed the full scope of Williams’ depravity.

The courtroom watched in stunned silence as prosecutors displayed portions of the police interrogation video. There was Williams, calm and collected, casually confessing to heinous crimes. At one point, he even looked up and smiled at the camera. When the image was frozen on screen, a collective gasp rippled through the courtroom.

“I wanted to illustrate just how calm and cool Williams was despite the gruesome nature of his sex assaults and murders,” Burgess told the court.

Then came the photographs—thousands of them. Images of Williams posing in stolen underwear, documenting his break-ins with meticulous detail. Pictures of his victims, bound and terrified, pleading for their lives. The prosecutor described—but mercifully did not show—videos Williams had recorded of his sexual assaults.

The evidence was so disturbing that several people in the courtroom had to leave. Victims’ family members sobbed openly. Even hardened reporters who had covered violent crimes for years found themselves shaken.

Court documents revealed that Williams had photographed himself in the underwear of young girls as young as 11 years old—twin sisters whose bedroom he had broken into. He had stolen 87 pieces of women’s and girls’ underwear, some belonging to victims who were minors.

During the assaults on his murder victims, Williams had forced both women to model their own lingerie while he photographed them. The recordings captured their desperate pleas for life.

Jessica Lloyd’s voice echoed in the courtroom through excerpts of the video Williams had made: “If I die, will you make sure my mom knows that I love her?”

Family members gasped. Many wept uncontrollably.

“Absolutely Despicable”

On October 21, 2010, Justice Scott delivered his sentence. His words were harsh and unsparing.

“Your crimes were utterly despicable,” the judge declared. “Your assault of the two women was vile and particularly depraved. The lives of two young women were senselessly taken, and the security and serenity of these peaceful, close-knit communities have been shattered”.

Williams was sentenced to two concurrent life sentences for the murders of Jessica Lloyd and Marie-France Comeau, with no possibility of parole for 25 years. He also received 120 years for the sexual assaults and break-ins, to be served concurrently.

Additionally, Williams was ordered to pay $8,800 to a victims’ fund—$100 for each count of breaking and entering.

The judge also ordered the destruction of Williams’ Nissan Pathfinder SUV, all the stolen underwear, and the explicit photographs and videos. The evidence was too dangerous to remain in existence, even under lock and key.

Williams showed no emotion as the sentence was read. He stood ramrod straight, hands clasped behind his back—the military bearing he had maintained throughout his career. He offered no apology to his victims, no expression of remorse.

As he was led away in handcuffs, family members of his victims watched in silence. For Jessica Lloyd’s brother Andy and Marie-France Comeau’s father, the sentence brought no comfort—only the grim satisfaction that Williams would spend the rest of his life behind bars.

The Military’s Response

The Canadian Forces moved swiftly to erase Russell Williams from their history. The day after his guilty plea, the military formally discharged him for “service misconduct”—the most serious violation possible.

In an unprecedented ceremony, four soldiers burned Williams’ uniforms, medals, and insignia in a symbolic act of repudiation. He became the first officer in Canadian military history to have his honors ceremonially destroyed.

At CFB Trenton, construction crews immediately gutted Williams’ former office, tearing up carpets, repainting walls, and replacing all furniture—anything to eliminate traces of the man who had commanded there.

His pilot’s wings were revoked. His photographs were removed from military installations. Every award he had earned over 23 years of service was stripped away.

But there was one thing the military couldn’t touch: Williams’ pension.

Under the Canadian Forces Superannuation Act, military pensions are protected from “attachment, seizure and execution”—meaning they cannot be revoked by the government or awarded to victims in civil lawsuits. Williams had contributed to the pension plan for more than two decades, and by law, the money was his.

The pension was estimated at $60,000 per year. This meant that Williams, sitting in prison, would collect approximately a quarter-million dollars in retirement benefits over the first four years of his incarceration alone.

The revelation sparked national outrage. Citizens called for the government to change the law, to strip murderers and rapists of military benefits. But as of his sentencing, no such legislation existed.

The Wife

Throughout the investigation, trial, and sentencing, one person was conspicuously absent: Mary Elizabeth Harriman, Williams’ wife of 19 years.

Harriman never attended a single court proceeding. She issued no public statements, gave no interviews, offered no explanations. The accomplished executive director of the Heart and Stroke Foundation—a woman respected in her own right—had become collateral damage in her husband’s crimes.

Court documents later revealed that Harriman had been “shocked and devastated” by the charges against Williams. She claimed to have had “absolutely no idea” about her husband’s double life. To her, Russell Williams had been a dedicated officer, a loving husband, a man she trusted implicitly.

In his confession, Williams had written a note to his wife: “Dearest Mary Elizabeth, I am so very sorry for having hurt you like this. I love you, Russ”.

But Harriman’s suffering was far from over. In 2011, Laurie Massicotte—one of Williams’ sexual assault victims—filed a $7 million lawsuit not just against Williams, but against Harriman as well. The lawsuit made an explosive allegation: that Harriman may have been aware of her husband’s “illicit conduct” but failed to report it to police.

The claim was met with skepticism from legal experts and the public alike. An Ontario Court of Appeal ruling described Harriman as “yet another victim of Williams’s depravity,” acknowledging the nightmare she had been thrust into through no fault of her own.

Still, the lawsuit dragged on for years. Massicotte sought to amend her claim to include Williams’ pension—arguing that the law protecting military pensions from seizure violated her Charter rights. She wanted compensation for the trauma Williams had inflicted, and she believed his retirement funds should be fair game.

Williams fought back from prison, opposing any attempt to touch his pension.

In 2016, after five years of legal wrangling, Massicotte finally reached a confidential settlement with Williams and Harriman. The terms were never disclosed, but the ordeal had taken its toll on everyone involved.

Harriman filed for divorce shortly after Williams’ conviction. But as of 2014—more than three years after initiating proceedings—they were still legally married. She continued living in their Ottawa home with Rosebud, one of the couple’s cats, and returned to work at the Heart and Stroke Foundation, where colleagues reportedly supported her.

Through it all, Harriman maintained her silence. The woman who had once shared her life with a monster chose privacy over explanation, grief over spectacle.

Where He Is Now

Russell Williams is currently incarcerated at Port-Cartier Institution, a maximum-security federal penitentiary in Quebec. He is held in solitary confinement, isolated from other inmates for his own safety. Even among criminals, former military officers who sexually assault women and murder them are despised.

Williams will not be eligible for parole until 2035, when he will be 72 years old. Given the nature of his crimes and the explicit evidence preserved by prosecutors, parole is unlikely.

In prison, Williams has all the money he needs. His military pension ensures he can afford anything available at the prison canteen—snacks, personal items, small comforts that other inmates cannot. It’s a bitter irony that the killer who destroyed so many lives continues to receive taxpayer-funded benefits.

There has been speculation over the years about Williams’ state of mind. According to reports, he attempted suicide shortly after his arrest by stuffing cardboard down his throat, trying to asphyxiate himself. The attempt failed, and he was placed under constant surveillance.

Legal experts have debated whether Williams qualifies as a serial killer. By FBI standards, a serial killer must commit at least three murders over a period of time. Williams committed two. But many believe that had he not been caught when he was, Jessica Lloyd would not have been his last victim. His crimes were escalating rapidly—from theft to sexual assault to murder in just over two years.

“He would have killed again,” one criminologist observed. “There’s no question in my mind”.

The Communities Remember

For the people of Belleville, Tweed, Brighton, and the surrounding areas, the wounds remain raw. These were small, tight-knit communities where people trusted their neighbors, left doors unlocked, and never imagined that a serial predator could be hiding in plain sight.

“The security and serenity of these peaceful communities have been shattered,” Justice Scott said at sentencing, and his words proved prophetic.

Every year on January 29, Jessica Lloyd’s friends and family gather to remember her. Her brother Andy has become an advocate for victims’ rights, working to ensure that Jessica’s story—and the stories of all Williams’ victims—are never forgotten.

“It’s been a journey,” Andy Lloyd said in 2025, marking the 15th anniversary of his sister’s death. “Some things get easier and some things don’t. But we keep her memory alive”.

Marie-France Comeau’s family has been less public in their grief, but the loss of the vibrant 38-year-old flight attendant left a void that can never be filled. Comeau had dedicated her life to serving Canada in the military—only to be betrayed and murdered by her own commanding officer.

The Unanswered Questions

More than a decade after Russell Williams’ arrest, questions still linger.

How did no one notice? How did a man engage in 82 break-ins, steal dozens of pieces of underwear, commit sexual assaults, and murder two women without raising suspicion?

Williams was meticulous in his crimes, yes—but he was also operating in plain sight. He attended military functions, commanded an air force base, interacted with hundreds of people daily. Yet not a single person detected anything wrong.

Some have pointed to the culture of the military, where officers like Williams are afforded enormous trust and respect. Others note that Williams deliberately targeted victims who lived near his isolated cottage, not in the Ottawa neighborhoods where he was well-known.

But perhaps the most disturbing answer is the simplest one: Russell Williams was exceptionally good at living a double life. He compartmentalized his existence, keeping his two identities entirely separate. At work, he was Commander Williams—disciplined, professional, trustworthy. At home, he was the predator—calculating, cold, remorseless.

“There was no outward sign,” one military colleague said after the arrest. “He seemed perfectly normal”.

And therein lies the horror: “perfectly normal” isn’t always what it seems.

The Legacy

The Russell Williams case fundamentally changed how Canadians view authority, trust, and safety. It shattered the comforting belief that military officers, police, doctors—people in positions of power and respect—are incapable of such evil.

Detective Jim Smyth’s interrogation became legendary in law enforcement circles, studied by police agencies around the world as a masterclass in psychological interviewing. The ten-hour confession remains one of the most complete admissions ever obtained from a serial predator.

For the victims—those who survived and the families of those who didn’t—the trial brought little closure. No sentence could restore what Williams had stolen: lives, innocence, peace of mind.

But perhaps there is a lesson in this darkness. Russell Williams’ crimes teach us that evil doesn’t always announce itself with obvious warning signs. It can wear a uniform, smile politely, and shake your hand. It can live next door, command respect, and hide in the most unlikely places.

The decorated colonel who flew the Queen across Canadian skies was also the monster who terrorized women in their own homes. Both identities were real. Both existed simultaneously.

And that, perhaps, is the most chilling truth of all.

News

The Face Hidden in Every Frame: The Jennifer Kesse Mystery

The Morning That Changed Everything A Life Built with Purpose The January sun rose over Orlando, Florida, painting the sky…

“What Really Happened to the Springfield Three? Inside America’s Greatest Unsolved Mystery”

The Last Normal Night The summer air hung thick and sweet over Springfield, Missouri, on the evening of June 6,…

After 46 Years, DNA Finally Whispered His Name: The Carla Walker Murder That Refused to Stay Cold

A Valentine’s Dance, A Stolen Life, and Nearly Half a Century of Waiting for Justice February 17, 1974, started like any other Sunday…

After 46 Years, DNA Finally Whispered His Name: The Carla Walker Murder That Refused to Stay Cold

A Valentine’s Dance, A Stolen Life, and Nearly Half a Century of Waiting for Justice February 17, 1974, started like any other Sunday…

The Hart Family Tragedy: The Perfect Instagram Family That Hid a Decade of Horror Before Driving Off a Cliff

When “Free Hugs” Became a Funeral Shroud: The Untold Story America Needs to Hear On March 26, 2018, a German…

“Kidnapped in Cleveland: The True Story of Three Women Who Refused to Give Up Hope After a Decade in Hell”

The morning of August 23, 2002, started like any other desperate morning in Michelle Knight’s life. She stood in…

End of content

No more pages to load