The Night of the Promise

Chicago, winter of 1956.

The streets were wrapped in quiet, the kind that follows Christmas when the city finally exhales. Shop windows still glowed with leftover lights; snow hung in the air like a memory refusing to melt. On South Damen Avenue, a small brick house sat beneath the hum of a streetlamp, the windows fogged from the warmth inside.

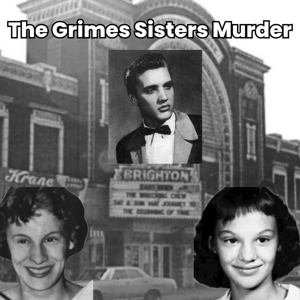

Inside that house lived Loretta Grimes — a single mother with seven children, a woman who had learned to keep moving no matter how heavy the world got. That December evening, she stood in her kitchen stirring a pot of stew while two voices drifted in from the back room — soft, girlish, singing in harmony to Elvis Presley’s “Love Me Tender.”

Barbara, fifteen, brushed the hair of her younger sister Patricia, thirteen. Both had the same dark eyes, the same bright energy that filled the little room like music itself.

“Mom,” Barbara called, “can we go see Love Me Tender again?”

Loretta sighed, the way only a tired mother can — half annoyance, half affection. It would be their eleventh time seeing the same movie. Eleven. Same theater, same songs, same dream.

“You’ve already seen it enough to act in it,” she teased.

Barbara grinned. “Please, Mom. Just one more time.”

Loretta hesitated. She looked at her girls — cheeks pink from excitement, hair brushed to a shine, their laughter floating like light through the cold house. “All right,” she said finally. “But you have to be home before midnight. Promise me.”

“We promise!” both girls said, almost in chorus.

At 7:30 PM, they bundled in their coats, slipped $2.50 into their purses — enough for two tickets, popcorn, maybe a Coke. Before stepping out, Barbara leaned in to hug her mother. “We’ll be home soon,” she said. Then the door shut behind them, and the winter air swallowed their laughter.

Loretta watched from the window as the two silhouettes disappeared down South Damen, walking hand in hand under the falling snow.

It would be the last time she ever saw them alive.

A City Wrapped in Innocence

Back then, Chicago was a city between two worlds — still holding onto the postwar dream but already tilting toward something louder, wilder, modern.

Teenagers were discovering rock ’n’ roll. Elvis was a revolution with a guitar. And Barbara and Patricia Grimes were part of that new heartbeat.

They were good girls — polite, churchgoing, giggling over record covers, scribbling “Mrs. Elvis Presley” in their notebooks. The Brighton Theater on Archer Avenue was their second home. Just a mile and a half away — an easy walk, safe, familiar. Everyone in the neighborhood knew the Grimes girls.

That night, December 28, 1956, the temperature hovered just below freezing but the air was calm. A perfect movie night.

Around 9 PM, one of Patricia’s friends, Dorothy Weinert, saw them in the theater. She sat behind them during the first showing and remembered the two sisters laughing, sharing popcorn, whispering when Elvis appeared on screen.

When the credits rolled, Dorothy left. The sisters stayed for the second showing. It ended around 11:15 PM. By then, the streets outside were dark and still. Most kids would have hurried home. But Barbara and Patricia didn’t.

No one knows exactly what happened after that final reel faded to black.

The Hours That Broke a Mother

Midnight came. Loretta glanced at the clock. The stew pot still sat on the stove, untouched. The house was quiet except for the ticking on the wall. She told herself they’d just missed the bus — maybe they stayed to watch the crowd leave. But by 12:30, the streets outside were empty.

At 2 AM, panic set in. Loretta reached for the phone, dialing the police.

“My daughters went to the movies,” she said, her voice trembling. “They promised to be home before midnight. They’re not back yet.”

The officer on duty sounded calm, detached. “They’re probably out with friends, ma’am. Maybe they’ll come home in the morning.”

But Loretta knew her girls. They weren’t the kind to stay out without a word. “They always come home on time,” she insisted.

By dawn, her hands were shaking too hard to make coffee.

She began calling neighbors, friends, relatives — no one had seen them. By afternoon, she was walking the route to the theater herself, her breath clouding in the cold. Each corner, each lamppost — familiar, harmless, but now holding the weight of dread.

That evening, the police finally opened an official missing persons case.

The Search Begins

What started as one mother’s plea soon became Chicago’s largest search in history.

By New Year’s Eve, more than 200 officers were mobilized. Thousands of volunteers scoured parks, alleys, abandoned lots, riverbanks. They looked under bridges, through garbage dumps, in old factories. Teenagers from local schools joined the search, carrying flashlights through the night.

Posters with the girls’ faces — smiling, identical in their joy — appeared on bus stops and streetcars. Radio stations repeated the call every hour. The Chicago Tribune ran their photos on the front page.

And as the days passed, Chicago began to ache.

This wasn’t just another disappearance. The Grimes sisters had become everyone’s daughters.

Loretta went on television, her eyes swollen, her voice cracking.

“If someone has my girls, please let them go. I won’t ask any questions. Just bring them home.”

Her words echoed across living rooms and diners. The city held its breath.

When Elvis Spoke

On January 11, 1957, two weeks after the girls vanished, the story reached Memphis. Elvis Presley, hearing about the sisters who adored him, spoke directly to the camera:

“If those two girls can see this, please go home. Your family’s worried. Everyone’s looking for you.”

It was a brief moment — thirty seconds on live TV — but it rippled through the country. Millions watched. Mothers wept. Fathers tightened their arms around sleeping children.

But the call brought no answer.

Chicago stayed cold.

And Loretta waited by the window, her faith shrinking with every dawn.

The Winter of Fear

The days after Elvis spoke to the camera should have brought hope.

Instead, they brought silence.

Chicago kept searching, but January’s cold tightened its grip. Snow piled high along the curbs, muffling the sound of the city. Each morning, Loretta opened the curtains hoping for a phone call, a note, a knock — anything. All she found was frost.

On the twenty-fifth morning, January 22, 1957, a man named Leonard Prescott was driving down German Church Road in Willow Springs, fifteen miles from the Grimes home. The road was quiet, lined with bare trees, snowbanks taller than fences.

Out of the corner of his eye, he noticed something — two pale shapes behind the guardrail. Flesh-colored, still, half-buried in snow.

He slowed down.

At first he thought they were mannequins, dumped from a truck.

He went home, told his wife Marie. She didn’t believe him. “You’re seeing things,” she said.

But he insisted. They drove back together.

Marie stepped out of the car, walked toward the guardrail, and screamed. Then she fainted.

They weren’t mannequins.

Two young girls lay side by side, their bodies turned slightly toward each other as if clinging for warmth. Barbara’s knees were drawn toward her chest; Patricia’s head rested against her sister’s arm.

The snow around them was undisturbed.

The Day Chicago Stopped Breathing

Within an hour, German Church Road filled with sirens and headlights. Police cars, reporters, volunteers — over a hundred people in heavy coats trudging through snow to see what no one wanted to see.

Joseph Grimes, the girls’ father, arrived to identify them.

He took one look and collapsed into the arms of an officer. “Those are my girls,” he whispered.

News spread faster than the wind that day. Radio stations broke programming. Newspapers sent photographers. Crowds gathered at Willow Springs, standing behind ropes, hats pulled low, faces pale.

Chicago — a city built on noise — fell quiet.

The Questions That Never Made Sense

The medical examiner’s report should have offered answers.

It didn’t.

The girls, he said, had died from exposure to the cold — “secondary shock due to low temperatures.” There were no gunshot wounds, no broken bones, no obvious signs of assault. But Barbara had small, round punctures on her chest — like those from a thin metal object. Patricia had bruises along her face and hands.

Time of death: within five hours of leaving the theater.

That meant the girls had died early on December 29, just hours after watching Love Me Tender.

If that was true, where had they been for the last twenty-five days?

How could so many people — witnesses, friends, strangers — swear they’d seen them alive in the weeks after?

A waitress in the city claimed she’d served them breakfast on December 30.

A bus driver said he’d seen two girls matching their description the following week.

A trucker swore he saw them with two men along Route 66.

The medical examiner dismissed it all. “Mistaken identity,” he said.

But the public wasn’t so sure.

The Man with the Dream

Then came a strange call.

Days after the disappearance — long before the discovery — a man named Walter Kranz had phoned the police. He said he’d dreamed where the girls would be found: “A road by a creek, near a guardrail, out past the city.”

When the bodies appeared in that exact setting, investigators froze.

Kranz was brought in for questioning. He told the same story over and over. “I saw it in a dream,” he insisted. “That’s all.”

They searched his home. They found nothing — no clothing, no evidence. Only a typewriter that, weeks later, was traced to an anonymous letter sent to the Grimes family demanding ransom.

Kranz denied writing it.

No charges were filed.

But the city whispered his name for months.

The Man Who Looked Like Elvis

In January, another lead surfaced.

A restaurant owner in the city’s north side told police about a man named Edward “Bennie” Bedwell — a drifter, 21, with slicked-back hair and sideburns like Elvis himself.

The owner claimed Bedwell had come in on December 30 with another man and two young girls who looked like the Grimes sisters.

One of the girls, he said, seemed dazed, almost asleep.

They ate, laughed, listened to music, then left in a car.

Bedwell was picked up within hours.

For three days, he was interrogated in a windowless room until he broke. He signed a confession saying he’d spent a week with the girls, taking them to bars, then “lost his temper” when they refused his advances. He said he left them “by the road.”

The confession made headlines. “Case Solved,” blared the Sun-Times.

But the celebration didn’t last.

At the hearing, Bedwell retracted everything. He said police had threatened him, refused him food, made him sign.

And the autopsy didn’t fit: the girls had been gone only hours, not days.

Loretta Grimes, watching from home, threw her coffee mug at the wall.

“They let my girls’ real killer go,” she cried on TV.

The public’s faith shattered with her.

The City of Rumors

For weeks after, Chicago became a hive of suspicion.

Every man who looked at a teenage girl too long was whispered about.

Every car parked too close to the curb was a threat.

Loretta received letters — some promising information, others cruel.

One claimed the girls had been “taken by truckers.”

Another said they’d “run off to Nashville to see Elvis.”

She stopped opening them after a while.

Detectives knocked on hundreds of doors.

Reporters wrote thousands of words.

But nothing — not a single solid lead — held up.

The case turned into fog.

And in that fog, a mother tried to live.

The House on South Damen

The Grimes home grew quieter by the week.

The radio still played Elvis, but Loretta couldn’t bear to listen.

She folded her daughters’ clothes, placed their hairbrushes on the dresser, and left the bedroom untouched.

The smell of their perfume lingered like memory itself — stubborn, sweet, refusing to fade.

Neighbors would see her at the window, cigarette in hand, staring at the street where her girls had last walked away.

She told a reporter once, softly, “I can still hear them laughing.”

But when asked if she believed she’d ever get justice, she just shook her head.

“Justice?” she said. “Justice would mean they come home.”

The Long Winter After

Time has a way of moving on, even when people can’t.

The streets thaw, the snow melts, the city returns to its noise — but grief has no calendar.

For Loretta Grimes, every morning began the same way: silence, a cup of coffee, and two empty chairs at the breakfast table.

Neighbors tried to help. They brought casseroles, said prayers, left flowers on the porch. But none of it filled the space her daughters left behind.

The laughter that once echoed through the small brick house on South Damen Avenue had turned into a quiet so deep it almost made the walls hum.

In the months that followed, Loretta gave interview after interview. She spoke on television, in newspapers, to anyone who would listen. Each time, her voice trembled but never broke.

“I just want them remembered,” she said. “Not for how they were found… but for who they were.”

Barbara loved to dance. Patricia wanted to be a teacher.

Both adored music, bubble gum, Saturday matinees, and the idea that Elvis Presley was somehow singing to them alone.

A City Haunted by Innocence

The case never truly left Chicago.

It stayed in headlines, in whispers, in late-night talk around kitchen tables.

Parents began walking their children to the movies instead of letting them go alone. Girls started carrying small pocket flashlights in their purses.

An entire generation grew up a little less trusting of the dark.

Detectives retired, then died. Files went missing, evidence degraded, memories blurred.

But the Grimes sisters never became just another statistic.

They became the city’s collective wound — the reminder that safety, even in familiar streets, can vanish without warning.

Some said the tragedy changed Chicago’s soul.

After 1956, the city grew cautious.

The laughter of teenage girls walking home at night never sounded quite the same.

The Family Left Behind

Loretta carried on because mothers do. She still had five other children who needed her — Jimmy, Joey, Theresa, and the younger ones.

She cooked, cleaned, worked, and prayed.

But every Christmas, she set out two extra plates. Every December 28, she lit two candles by the window.

She once told a reporter from the Chicago Daily News,

“I still make their beds every week. It makes me feel like they’re just… away for a little while.”

As years passed, the Grimes children grew up, had families of their own. Some spoke of Barbara and Patricia often, others couldn’t bear to.

Theresa, one of the younger sisters, would later say,

“People tell you to move on. But how do you move on from your own blood?”

The house at 3634 South Damen stood for decades, unchanged. Neighbors swore they could sometimes hear faint music through the windows on winter nights — an old song, soft and sweet, like a record spinning in another world.

The Detectives Who Never Let Go

In the 1970s, long after the case went cold, a retired officer named Raymond Johnson took an interest in it again. He reviewed the files, interviewed surviving witnesses, and even tried to apply new forensic methods.

But most evidence had vanished.

Photographs had faded, and key documents were lost during a department move.

“Too many people with too many stories,” he said. “And too much time gone by.”

Still, he kept a copy of the sisters’ photos on his desk.

When asked why, he answered simply,

“Because they never got justice. Somebody has to remember.”

Even today, the Cook County Sheriff’s Office lists the Grimes case as open. The file sits in a metal cabinet, thick with dust, waiting for a miracle that may never come.

Loretta’s Last Winter

Loretta lived until the mid-1980s.

She never moved away, never remarried.

Every December, reporters would call, asking if she still believed the truth would come out.

“I stopped asking why,” she said once. “I just ask that people don’t forget.”

When she passed away, neighbors lined the street for her funeral. The church played “Love Me Tender.” Some said it was fitting; others said it was too painful.

Her surviving children placed two white roses on her coffin — one for Barbara, one for Patricia.

They said goodbye to their mother, but also, somehow, to the last piece of that long Chicago winter.

The City That Still Whispers

Decades later, the story continues to echo — not in headlines, but in memory.

True crime writers revisit it every few years.

Retired officers talk about it at reunions.

Old Chicagoans, when snow begins to fall, still say softly, “Remember the Grimes girls.”

It isn’t fear that keeps the story alive. It’s tenderness — the ache of two young lives frozen in time, and the mother who never stopped waiting.

Some believe that somewhere, someone still knows the truth. Maybe they’ve carried it in silence all these years. Maybe they told it once, but no one listened.

But time, like snow, covers everything eventually.

Epilogue: Two Girls and a Song

Barbara and Patricia Grimes were just two sisters who loved music and believed the world was kind.

They had dreams of growing up, of dancing to Elvis songs in their living room, of finding love one day.

They didn’t live long enough to see what the world could become — both brighter and darker than they ever imagined.

Their story isn’t just a mystery; it’s a mirror.

It reminds us that even the most ordinary night can hold a tragedy, and that love — stubborn, foolish, eternal — outlives even the coldest winters.

So every time “Love Me Tender” plays, somewhere between the notes and the silence, there’s a whisper — two voices, young and clear, still singing along.

Love never dies.

Hope never fades.

But some promises never find their way home.

News

The Face Hidden in Every Frame: The Jennifer Kesse Mystery

The Morning That Changed Everything A Life Built with Purpose The January sun rose over Orlando, Florida, painting the sky…

“What Really Happened to the Springfield Three? Inside America’s Greatest Unsolved Mystery”

The Last Normal Night The summer air hung thick and sweet over Springfield, Missouri, on the evening of June 6,…

After 46 Years, DNA Finally Whispered His Name: The Carla Walker Murder That Refused to Stay Cold

A Valentine’s Dance, A Stolen Life, and Nearly Half a Century of Waiting for Justice February 17, 1974, started like any other Sunday…

After 46 Years, DNA Finally Whispered His Name: The Carla Walker Murder That Refused to Stay Cold

A Valentine’s Dance, A Stolen Life, and Nearly Half a Century of Waiting for Justice February 17, 1974, started like any other Sunday…

The Hart Family Tragedy: The Perfect Instagram Family That Hid a Decade of Horror Before Driving Off a Cliff

When “Free Hugs” Became a Funeral Shroud: The Untold Story America Needs to Hear On March 26, 2018, a German…

“Kidnapped in Cleveland: The True Story of Three Women Who Refused to Give Up Hope After a Decade in Hell”

The morning of August 23, 2002, started like any other desperate morning in Michelle Knight’s life. She stood in…

End of content

No more pages to load