The snow began to fall by mid-afternoon, soft as a hush inside a church.

Fifth Avenue shimmered with carriages and women in furs — wealth meeting winter in perfect rhythm.

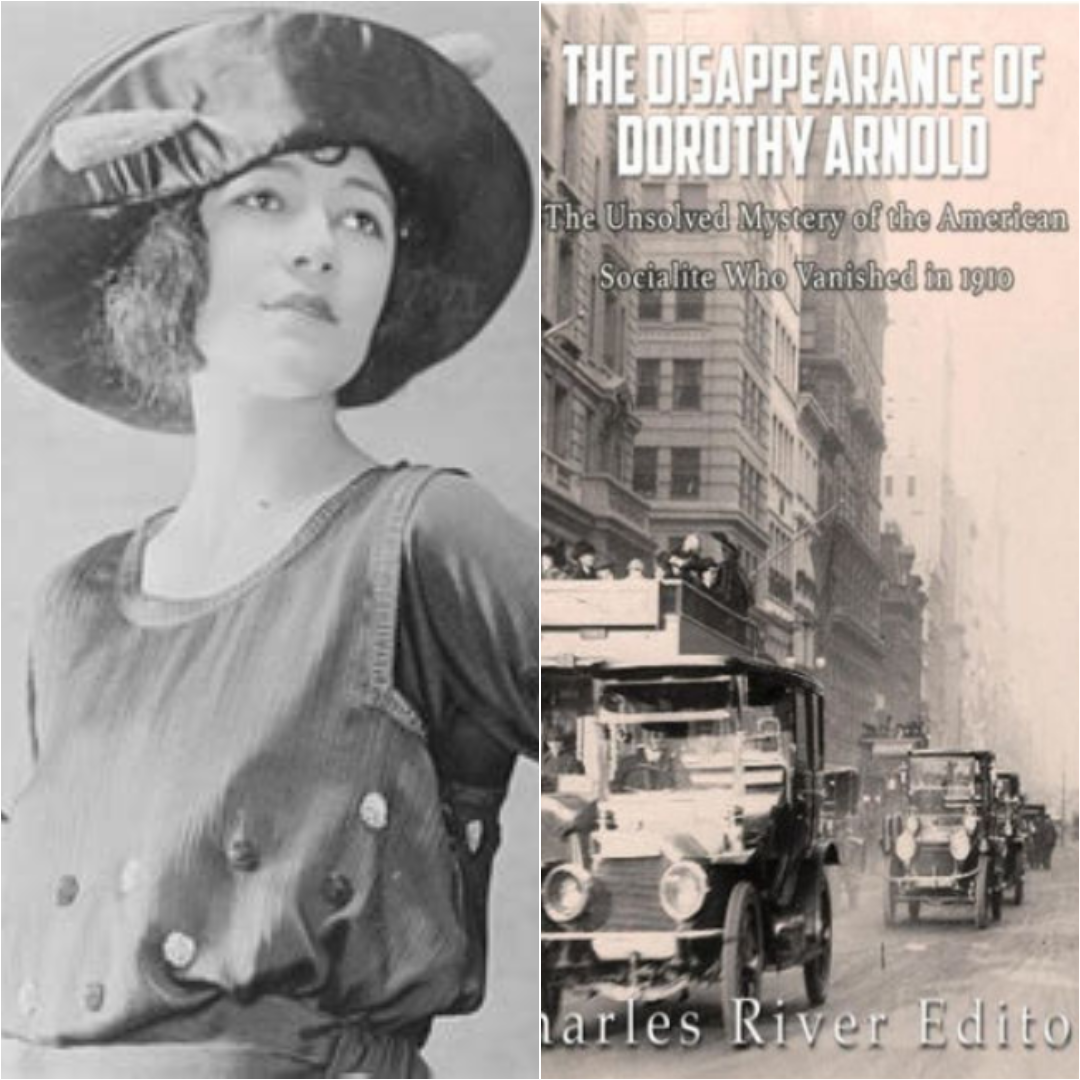

Among them walked a young woman in a tailored blue coat and velvet-trimmed hat.

No escort, just quiet confidence that caught the light like frost on glass.

Her name was Dorothy Harriet Camille Arnold.

By sunset, she would vanish without a trace.

To know Dorothy was to understand contradiction.

Her father, Francis R. Arnold, was a respected importer — a man who valued reputation like gold.

The Arnolds lived on East 79th Street in a marble-stepped brownstone where servants spoke in whispers.

Dorothy, second of four children, had graduated from Bryn Mawr College — rare for women of her class.

She loved poetry, city skylines, and the dream of publishing her own short stories.

Her father disapproved.

“A lady’s name should appear in print only at birth, marriage, and death,” he warned.

Dorothy smiled but stayed silent — her rebellion soft but steady.

She mailed manuscripts to McClure’s Magazine.

Each rejection slip she folded carefully and hid inside her vanity drawer.

December 12, 1910.

Dorothy left home around eleven.

She told her mother she was shopping for an evening gown.

She carried thirty dollars and a small story draft titled Lotus Leaves.

At Brentano’s Bookstore she bought Engaged Girl Sketches by Emily Calvin Blake.

The clerk remembered her as cheerful, talking about books before walking north toward Central Park.

That was the last time anyone saw her.

When she didn’t return for dinner, the family assumed she was with friends.

When midnight passed, worry turned to dread.

They didn’t call police.

Not the next day, nor the day after.

To have their name under MISSING would, Mr. Arnold said, “bring disgrace.”

Instead, they made quiet inquiries.

Pinkerton detectives searched boarding houses and city morgues under false names.

Nothing.

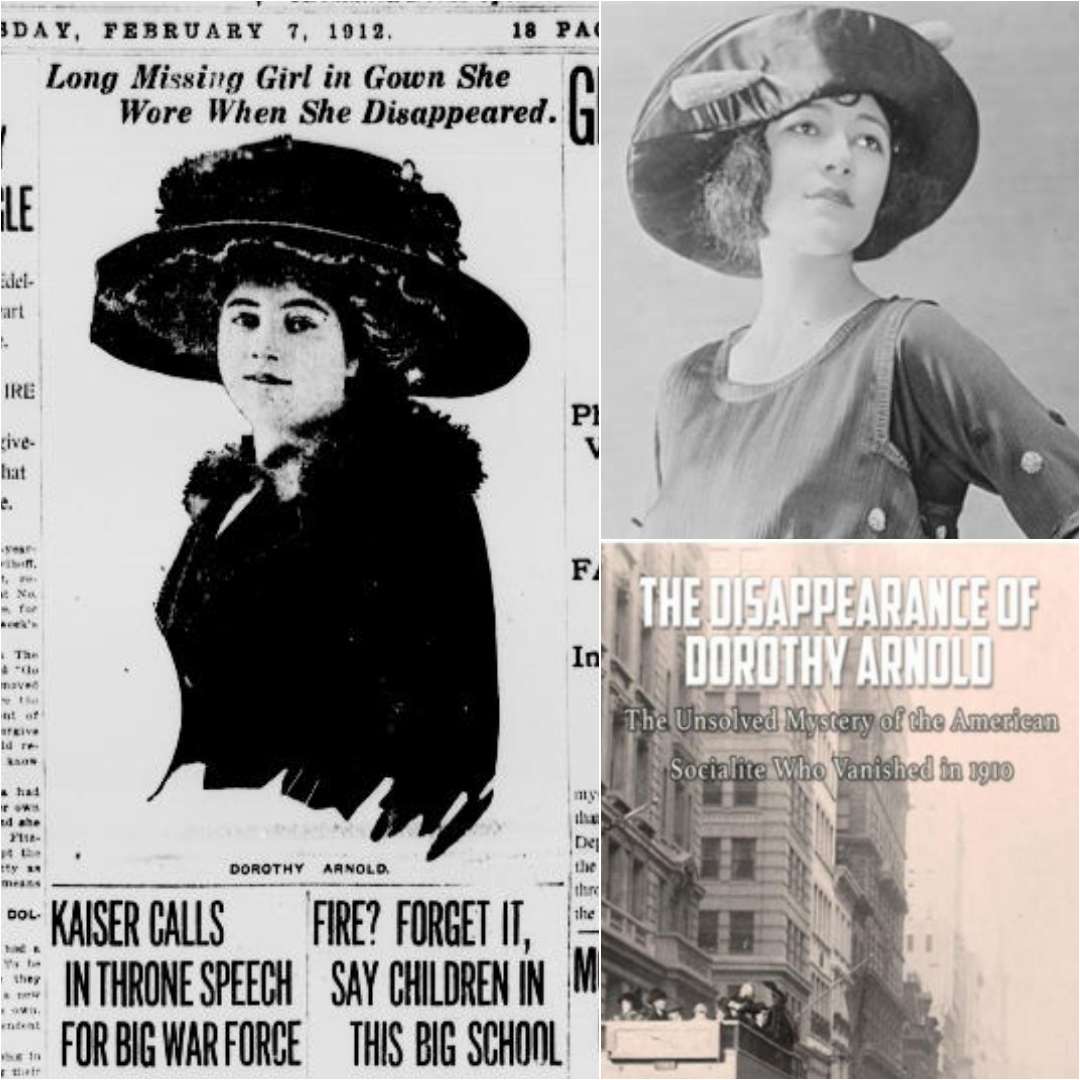

After six weeks, the secret burst.

On January 25, 1911, The New York Times headline read:

“HEIRESS DOROTHY ARNOLD DISAPPEARS — FAMILY FEARED FOUL PLAY.”

Overnight, America was captivated — beauty, privilege, mystery, and tragedy wrapped in one blue coat.

Rumors flooded in.

She’d eloped.

She’d taken her own life after rejection.

She’d been kidnapped.

A witness in Pittsburgh saw her with a tall stranger; another in Boston swore she lived under a new name.

Each clue faded into shadow.

Detectives questioned George Griscom Jr., a young engineer and secret companion from a wealthy family.

He admitted affection but denied any role.

The tabloids tore him apart.

Mr. Arnold forbade his name ever be spoken again.

For months, New York lived on whispers.

Street vendors sold postcards of her face.

Tabloids printed “letters” she’d never written.

Dorothy became both symbol and ghost — a portrait of a generation’s restlessness.

By summer, her father broke.

“She is dead,” he told reporters.

“We shall not recover her body. That is all.”

But Mrs. Arnold refused surrender.

Every birthday she placed lilies by the window and kept a hallway lamp burning through the night.

In 1914, a trunk surfaced in a Pennsylvania boardinghouse.

Inside: women’s clothes, initials “D.A.”, a copy of Lotus Leaves.

Mr. Arnold called it “a cruel hoax.”

The trunk soon vanished from evidence.

That same year, a letter reached The Evening Sun:

“I am safe and well. You will hear of me soon.” — Dorothy

Experts dismissed it.

Yet one detective whispered, “That handwriting… it was close.”

Years slid by.

New York forgot — or pretended to.

Still, on foggy nights along Fifth Avenue, people claimed they saw her reflection in shop windows:

a young woman in blue, walking briskly against the wind, disappearing before the light changed.

February 6, 1915 — Mrs. Arnold’s Journal

I saw a girl in a blue coat today.

For a heartbeat I thought it was her.

I stood up so fast my chair fell.

The girl smiled — not Dorothy’s smile, but kind enough that I pretended it was.The house is quiet now.

Francis never says her name.

I no longer ask God for her return — only that if she died alone, someone held her hand.At night I open the window and imagine her walking home.

I tell her the light is still on.

By the 1920s the world had changed — war, jazz, the crash.

Fifth Avenue glowed brighter, carriages replaced by taxis, lilacs by gasoline.

But sometimes, in the reflection of glass, an older New Yorker swore they saw her —

a young woman in blue, turning once before vanishing into the crowd.

And yet, Fifth Avenue never gave her back.

Time did what it always does — it softened edges, blurred details, and made the unbelievable sound ordinary.

But for the Arnolds, nothing about the years after 1910 was ordinary.

The brownstone on East 79th Street stood as it always had — polished, grand, and heartbreakingly still.

Visitors said it felt like a museum of a family that had once been alive.

Dorothy’s room was never touched.

Her gloves remained folded in a drawer.

Her hairbrush stayed on the vanity, a single strand still tangled in its bristles.

Outside, the world moved on.

The Titanic sank.

Women marched for the vote.

New York built higher, louder, and faster.

But inside that house, time refused to pass.

The Father’s Search

Francis R. Arnold aged ten years in one.

Though he had told reporters his daughter was dead, he continued to pay detectives privately — men who traveled from New York to Paris, London, and even Naples, chasing rumors that she had fled abroad.

One letter, found decades later in a Pinkerton file, described a woman fitting Dorothy’s description working as a governess for a family in Florence.

When investigators arrived, the woman had already disappeared.

Another clue — a trunk in California with initials D.A. burned into the leather — turned out to belong to a “Deborah Allen.”

Every lead ended in smoke.

By 1914, Francis stopped granting interviews.

He refused condolence letters and burned several that arrived anonymously, some claiming to know “where she rests.”

When he died in 1922, his will made no mention of Dorothy.

He left her portion of the inheritance to charity — a final gesture of control from a man who could not control the truth.

The Mother’s Silence

After her husband’s death, Mrs. Arnold rarely left the house.

Neighbors sometimes glimpsed her at the window, reading by lamplight long past midnight.

In her later years she took to writing short notes to her missing daughter — small slips of paper placed under a porcelain vase in Dorothy’s room.

You would be 35 today. I hope you still love lilacs.

I found your blue ribbon. It still smells of perfume.

She never signed them.

The Letters That Wouldn’t Stop

Even as decades passed, the case refused to die.

The New York Times, Herald Tribune, and later Life Magazine revisited it every few years under nostalgic headlines —

“THE GIRL WHO WALKED OFF FIFTH AVENUE.”

Each anniversary brought a new wave of tips, each colder than the last.

In 1928, a letter arrived at police headquarters from an asylum in Florida.

A patient claimed to be Dorothy Arnold and demanded her inheritance.

Investigators dispatched two officers.

They returned with photographs — the woman was older, sharper-faced, missing a front tooth.

Mrs. Arnold looked at the pictures and shook her head.

“No,” she said softly. “My Dorothy smiled with both lips.”

By the 1930s, people had turned her into folklore — a ghost story told at dinner parties.

A woman in blue still wandering Fifth Avenue.

A carriage stopping for a passenger no one could see.

A name whispered in the fog.

New York’s Obsession

Historians later said the case had captured the city because it felt so modern — a young woman stepping into a world that wasn’t ready for her.

Dorothy’s disappearance arrived at the edge of a century learning to define women differently.

She wasn’t murdered for money or passion; she simply vanished in the space between expectation and freedom.

To older readers, she became a reminder of fragility.

To the young, a symbol of rebellion.

To the police, an embarrassment.

Her story outlived everyone who knew her.

When Mrs. Arnold died in 1928, her obituary did not list Dorothy among the survivors.

But a private nurse later told reporters that on her last night, Mrs. Arnold murmured a single sentence before drifting to sleep:

“Keep the light on, Dorothy. You’ll find the door.”

A Century Later

By the time skyscrapers pierced the skyline and Fifth Avenue turned into a canyon of glass, Dorothy Arnold had become legend.

True-crime authors speculated she had fallen victim to an illegal abortion, or had fled to Europe under another name.

Some even suggested the family discovered the truth but kept it secret to protect the Arnold reputation — that she was buried quietly under another stone.

No proof ever surfaced.

In 2010, on the centennial of her disappearance, The New Yorker ran a retrospective calling her “New York’s Original Missing Girl.”

Readers flooded the comment sections with theories.

A genealogist claimed to have traced her to a marriage record in Canada — false.

A retired librarian swore she had seen an identical face in a 1920 passport photo — inconclusive.

One photograph stood out: a crowd scene from 1911 showing a woman in a blue coat crossing the street as the camera caught her mid-step.

Was it Dorothy?

No one could say.

But the image went viral a century too late — another echo refusing to fade.

The City’s Ghost

Today, if you walk along Fifth Avenue in winter, the city sounds not unlike it did in 1910.

The hiss of tires replaces the clop of hooves, but the rhythm is the same.

Sometimes, when dusk turns the shop windows into mirrors, a shape flickers by — a reflection that doesn’t match the crowd.

Tour guides still mention her name softly near 79th Street, where her family home once stood before being replaced by an apartment tower.

A few residents say that, in the elevator at night, the lights occasionally dim for no reason.

They joke it’s Dorothy coming home.

But there’s a plaque on the building’s outer wall, placed quietly in 2015 by a historical society.

It reads:

In memory of Dorothy Arnold — a daughter of New York who walked into its heart and was never seen again.

An Imagined Letter (Mrs. Arnold’s Final Entry)

October 3, 1928

My dearest Dorothy,

I dreamed last night you were standing at the foot of the stairs, wearing that blue coat. I asked where you had been, and you said, “Just shopping, Mama.” I almost believed it. The morning light woke me before I could answer.

They say time heals, but time is only silence that grows thicker around a name. The city has changed, but when it rains on Fifth Avenue, I still hear your footsteps. I still turn my head.

If you found peace, hold on to it. If you are still wandering, look for the light. It is still burning.

Love always,

Mother.

Some mysteries fade when solved.

Others endure precisely because they never are.

Dorothy Arnold’s story is one of those — a reminder that behind every headline was once a heartbeat, behind every disappearance, someone waiting at a window.

And when the snow falls on Fifth Avenue, some swear you can still see her — the girl in blue, carrying a book, walking toward a future only she could see.

The light, even now, is still on.

News

The Face Hidden in Every Frame: The Jennifer Kesse Mystery

The Morning That Changed Everything A Life Built with Purpose The January sun rose over Orlando, Florida, painting the sky…

“What Really Happened to the Springfield Three? Inside America’s Greatest Unsolved Mystery”

The Last Normal Night The summer air hung thick and sweet over Springfield, Missouri, on the evening of June 6,…

After 46 Years, DNA Finally Whispered His Name: The Carla Walker Murder That Refused to Stay Cold

A Valentine’s Dance, A Stolen Life, and Nearly Half a Century of Waiting for Justice February 17, 1974, started like any other Sunday…

After 46 Years, DNA Finally Whispered His Name: The Carla Walker Murder That Refused to Stay Cold

A Valentine’s Dance, A Stolen Life, and Nearly Half a Century of Waiting for Justice February 17, 1974, started like any other Sunday…

The Hart Family Tragedy: The Perfect Instagram Family That Hid a Decade of Horror Before Driving Off a Cliff

When “Free Hugs” Became a Funeral Shroud: The Untold Story America Needs to Hear On March 26, 2018, a German…

“Kidnapped in Cleveland: The True Story of Three Women Who Refused to Give Up Hope After a Decade in Hell”

The morning of August 23, 2002, started like any other desperate morning in Michelle Knight’s life. She stood in…

End of content

No more pages to load