September 5, 1982 — When My World Ended

Before the Darkness

I need you to understand something before I tell you this story: I knew what loss felt like long before my son disappeared.

I was nineteen when I married my first husband. We were babies ourselves, really—two kids in love in eastern Iowa, building a life, having children of our own. We had two beautiful babies. Life felt full and possible.

And then God—or fate, or whatever cruel force runs this universe—decided I hadn’t suffered enough.

One night, a tornado ripped through our small town. I can still hear the sound of it—that terrible roaring, like a freight train coming to swallow everything whole. I was separated from my children in the chaos. When the wind finally stopped, I ran through the wreckage, screaming their names.

I found them lying face down in a pile of gravel and broken glass.

I thought they were dead. I knew they were dead. I collapsed beside them, and I remember thinking, “This is it. This is the moment my life ends.”

And then the rain came. Cold, hard rain pounding down on all of us. And the second those raindrops hit my babies’ backs, they started screaming.

They were alive.

Two months later, my husband died of cancer.

I was twenty-one years old, a widow with two children and a pile of hospital bills. People told me I was strong. People told me I’d survive this. And I did. I clawed my way back to something resembling life. I worked. I raised my kids. I even fell in love again.

I met John Gosch Sr. about two years after my first husband died. John was solid, steady, kind. We married, and on November 12, 1969, we had a son. We named him John David, but everyone called him Johnny.

That little boy—God, that little boy—he was my second chance at happiness. He was proof that life could be good again, that I could rebuild, that I could be whole.

For twelve years and nine months, I got to be his mother.

And then, on a Sunday morning in September, someone stole him from me.

The Last Morning

September 5, 1982. A date burned into my brain like a brand. I can tell you what the weather was like (cool, not quite fall yet), what I was wearing (my nightgown), what I was planning to make for breakfast (pancakes, Johnny’s favorite).

I can tell you every single detail of that morning—except the one that matters most.

I can’t tell you why I didn’t get up when Johnny left the house.

He’d been a paperboy for the Des Moines Register for over a year. Every Sunday, he and his dad would wake up before dawn, load up that little red wagon, and deliver papers through our West Des Moines neighborhood. Johnny loved that job. He was so proud of it. He’d won a perfect service award just weeks before—never a single complaint, never a late delivery.

But that morning, for some reason I will never understand, Johnny decided to go alone.

I heard him moving around the house around 5:45 a.m. I heard him getting ready. I heard the front door creak open.

I should have gotten up. I should have kissed him goodbye. I should have told him I loved him.

But I was tired. And it was early. And Johnny was twelve years old, responsible, capable. What could happen on a quiet Sunday morning in our safe, suburban neighborhood?

So I stayed in bed.

I let my son walk out that door with our little dachshund, Gretchen, and his red wagon full of newspapers.

I never saw him again.

For forty-three years, I’ve lived with that choice. Every single day, I wake up and the first thought in my head is: Why didn’t you get up? Why didn’t you stop him? Why didn’t you save him?

When I Knew

The phone started ringing around 7:45 a.m.

The first call was from a customer complaining their paper hadn’t been delivered. I felt a small flutter of worry, but I pushed it down. Maybe Johnny had just gotten his houses mixed up. Maybe he’d double back and fix it.

Then the phone rang again. Another customer. No paper.

And again. And again.

By the fourth call, my hands were shaking so badly I could barely hold the receiver. John saw my face and got dressed without a word. He went out looking for Johnny while I stayed by the phone, my heart pounding so hard I thought I might vomit.

I kept telling myself there was a reasonable explanation. Maybe Johnny had gotten hurt—sprained his ankle, needed help. Maybe he’d run into a friend and lost track of time. Maybe—

But I already knew.

Mothers know. People say that like it’s some kind of comfort, but it’s not. It’s a curse. Because I knew, deep in my bones, that something terrible had happened to my son, and there wasn’t a damn thing I could do about it.

When John came home thirty minutes later, his face told me everything before he even opened his mouth.

“I found his wagon,” he said quietly. “Still full of papers. About two blocks from here. Gretchen came home on her own.”

“Where’s Johnny?”

He just shook his head.

I ran to the phone and called the police. My voice was shaking, but I forced the words out: “My son is missing. He’s twelve years old. He was delivering newspapers and he’s gone. You need to send someone right now.”

The officer on the other end of the line sounded almost bored.

“How long has he been missing, ma’am?”

“About two hours.”

“We can’t file a missing person report until he’s been gone seventy-two hours.”

I felt like I’d been punched in the stomach.

“Seventy-two hours? He’s twelve. He didn’t run away. Something happened to him—”

“Ma’am, most kids turn up on their own. He probably just went to a friend’s house.”

“He was working. He wouldn’t abandon his job. Please, you have to—”

“I’m sorry, ma’am. That’s the policy. Seventy-two hours.”

He hung up.

I stood there holding that dead phone, and I felt something break inside me. Not my heart—that would come later, over and over again. What broke in that moment was my faith. My faith in the system. My faith that the people who were supposed to protect us would actually do their jobs.

Seventy-two hours. Three full days. They wanted me to sit in my house and wait while my twelve-year-old son was out there—God knows where, God knows with whom—maybe hurt, maybe terrified, maybe dying.

I didn’t wait.

John and I got in the car and started driving. We searched every street, every park, every empty lot. We knocked on doors until our knuckles bled. We called Johnny’s name until our voices gave out.

We found nothing.

By the time the sun set that night, I had aged a thousand years.

The Witnesses They Ignored

It took a full day before the police finally started investigating. And when they did—when they finally started talking to witnesses—we learned the truth.

My son had been taken.

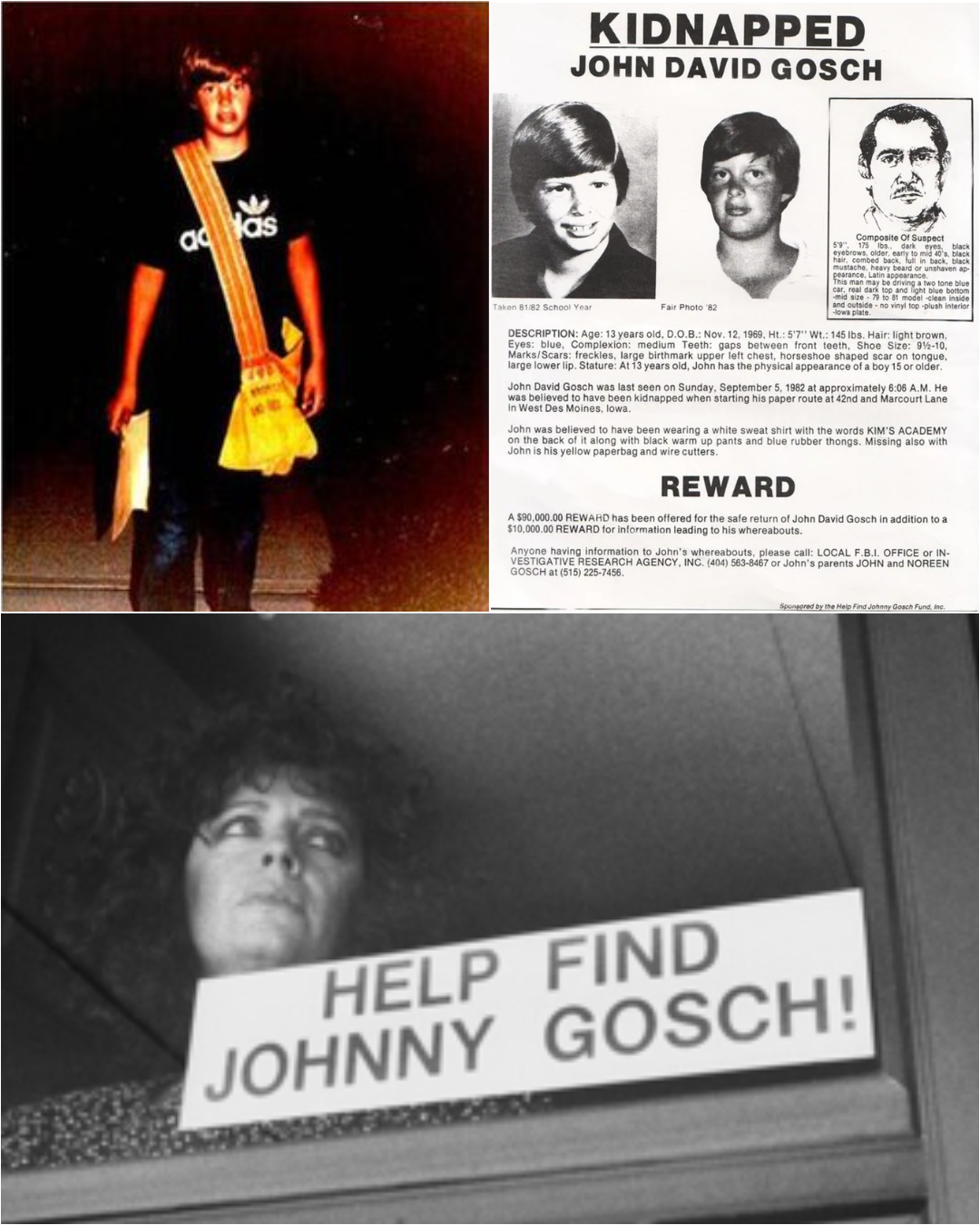

Multiple paperboys had seen Johnny that morning talking to a stocky man in a blue two-toned car. The man had been parked near the newspaper pickup spot for at least twenty minutes before Johnny arrived. One boy said something about him felt “off”.

Then there was John Rossi, a father helping his own son deliver papers. He saw Johnny approach the man’s car. Johnny even came over to Rossi and asked him to help give the man directions to 86th Street.

Rossi told me later—years later, with tears streaming down his face—that he knew something was wrong. He tried to memorize the license plate. He watched as the man reached up and flicked his dome light on and off three times, like he was signaling someone.

But when the police questioned him, Rossi couldn’t remember the exact plate number. He could only recall that it was from Warren County, Iowa.

That license plate haunted him for decades. He even underwent hypnosis, desperate to pull those numbers from his subconscious. But they never came.

There were other witnesses too. Another paperboy who saw a man following Johnny north on his route. A neighbor who heard a car door slam and watched a silver Ford Fairmont speed away, tires squealing on the pavement.

All the pieces were there. All the evidence pointing to one horrible truth: my twelve-year-old son had been kidnapped in broad daylight.

And do you know what the Des Moines Police Chief told the media?

“We believe Johnny Gosch ran away from home”.

I wanted to reach through the television and strangle him with my bare hands.

In the days and weeks after Johnny disappeared, I did something that made people hate me.

I didn’t cry on camera.

Oh, I cried. God, did I cry. I cried until there was nothing left inside me but a hollow ache. I cried in the shower so my other children wouldn’t hear. I cried in Johnny’s bedroom, clutching his pillow, breathing in the fading scent of him. I cried in my car, pulled over on the side of the road, screaming at God or the universe or whoever was listening.

But I didn’t cry on television.

And for that, they called me “The Ice Woman”.

They said I was cold. Unfeeling. One particularly cruel person suggested that I must have been involved in Johnny’s disappearance because “no real mother could be that calm”.

Here’s what those people didn’t understand: I couldn’t afford to cry on camera.

This was 1982. There was no Internet. No social media. No way to reach millions of people with the click of a button. If I wanted to find my son, I needed media coverage. And media coverage came in five-minute segments on the evening news.

Five minutes. That’s all I had to make people remember Johnny’s face. To make them care. To make them look twice at the blonde boy walking down the street or sitting in a restaurant.

If I spent those five minutes sobbing incoherently, people would feel sorry for me for a moment. And then they’d forget.

But if I showed up composed, articulate, and angry—angry at the system that had failed my son, angry at the police who wouldn’t take me seriously, angry at a world where children could be stolen in broad daylight—people would listen.

So I became the Ice Woman. I gave interview after interview with a steady voice and dry eyes. I testified before Congress. I spoke at conferences and town halls. I demanded changes to how missing children cases were handled.

And people hated me for it.

They said I was too controlled. Too analytical. Too cold.

What they didn’t see were the nights I couldn’t get out of bed. The mornings I couldn’t eat. The moments I genuinely wanted to die because the pain of living without Johnny was too much to bear.

But I didn’t die.

Because somewhere out there, my son needed me to keep fighting.

Fighting Monsters — The Years That Broke Me

When the Police Gave Up, I Hired My Own Army

By October 1982, it was clear that the West Des Moines Police Department had given up on finding Johnny.

Oh, they’d never say it out loud. They’d tell the media they were “following leads” and “investigating all possibilities.” But I could see it in their eyes every time I called. I could hear it in their voices when they returned my messages days later instead of hours.

They thought my son was dead. Or worse—they thought I was crazy.

So I did what any mother would do: I took matters into my own hands.

John and I sold everything we could. We took out loans. We held fundraisers—bake sales, garage sales, anything to scrape together enough money to hire private investigators. Because if law enforcement wouldn’t find our son, we’d damn well find him ourselves.

The first investigator we hired was Jim Rothstein, a retired NYPD detective with decades of experience. He’d worked on some of the most brutal cases in New York City, and he didn’t flinch when I told him what I suspected: that Johnny had been taken by an organized ring, that this wasn’t some random kidnapping.

Jim believed me. God, do you know what that meant? To have someone—anyone—look me in the eye and say, “I believe you”?

Then we brought in Ted Gunderson, a former FBI agent who’d retired as the head of the Los Angeles bureau. Ted had connections everywhere. He started digging, following leads the local police had dismissed or ignored entirely.

What they found terrified me.

They found patterns. Networks. Whispers of powerful people involved in things so dark I could barely comprehend them. They told me Johnny wasn’t the first, and he wouldn’t be the last.

But here’s the thing about the truth: no one wants to hear it when it’s ugly.

The Des Moines police dismissed everything my investigators found. They called them conspiracy theorists. Paranoid. Chasing shadows.

The press started calling me “The Ice Woman” because I refused to cry on camera, but they had no idea I was drowning.

August 12, 1984: It Happened Again

I’ll never forget the phone call.

It was a warm Sunday morning, almost exactly two years after Johnny disappeared. I was getting ready for another round of speaking engagements—John and I had been driving fifty miles after work to speak at community awareness programs, begging people to watch for our son.

The phone rang. It was one of my private investigators.

“Noreen, you need to turn on the news. Right now.”

I grabbed the remote, and the second the screen flickered to life, my blood turned to ice.

Another paperboy. Another Des Moines neighborhood. Another Sunday morning.

Eugene Martin. Thirteen years old. Disappeared while delivering newspapers for the Des Moines Register—the exact same paper Johnny had delivered.

I felt like someone had reached into my chest and squeezed my heart until it stopped beating.

Because months earlier—months before Eugene disappeared—one of my investigators had told me it was going to happen. He told me another paperboy would be taken from the south side of Des Moines, the second weekend in August.

And it happened. Exactly as he predicted.

I called the police immediately, frantic. “Don’t you see? This proves it! This proves Johnny was taken by an organized group! They’re doing it again!”

The detective on the other end of the line sighed like I was exhausting him. “Mrs. Gosch, we have no evidence linking the two cases.”

“No evidence? A paperboy disappears on a Sunday morning in the same city, for the same newspaper, under the same circumstances, and you see no connection?”

“We’re treating each case individually.”

I wanted to reach through the phone and shake him until his teeth rattled.

Six witnesses saw Eugene talking to a strange man that morning. Just like Johnny. The FBI even brought in a specialist to create a composite sketch. Just like Johnny.

But the authorities insisted the cases weren’t connected.

Eugene’s mother, Nancy, and I became sisters in grief. We’d meet for coffee, two women who’d lost their boys to the same monster, and we’d cry together. We’d rage together. We’d plot together.

And then, in March 1986, a third boy disappeared. Marc Allen, thirteen years old, vanished on a Sunday evening while walking to a friend’s house.

Three boys. Three families destroyed.

And still, the police said they couldn’t prove a connection.

The Predator in Plain Sight

In November 1986, a Des Moines Register circulation manager named Wilbur Milhouse was arrested.

When the police searched his home, they found something that made my stomach drop: a list of over 2,000 names and phone numbers of young boys. Most of them were paperboys for the Des Moines Register.

Milhouse claimed he used the list to recruit new carriers. But investigators discovered he was part of a local pedophile ring.

I knew immediately that he was connected to Johnny’s case. How could he not be? He had access to hundreds of boys—their routes, their schedules, their home addresses.

But the police never officially connected him to Johnny’s disappearance. They said there wasn’t enough evidence.

Wilbur Milhouse hanged himself in prison before anyone could get answers from him.

Sometimes I wonder how many secrets died with him.

The Scammers Who Fed on My Hope

The worst part about having a missing child? The vultures.

In 1985, I received a letter from someone calling himself “Samuel Forbes Dakota.” He said he’d been a guard for an outlaw motorcycle club that trafficked children. He said he’d personally seen Johnny—watched him get sold to a high-level drug dealer in Mexico City.

He said he could get Johnny back. For a price.

I knew it was probably a scam. God, I knew it. But what if it wasn’t? What if there was even a one percent chance this man actually knew where my son was?

We sent him $11,000. Then he asked for $100,000 more.

The FBI caught him at the Canadian border. His real name was Robert Hermann Mear, and he was nineteen years old. When Johnny disappeared in 1982, Mear was only sixteen.

The FBI said I’d been scammed. They said Mear made the whole thing up.

But here’s what haunts me: I still believed him. Part of me still does. Because what if—what if—some tiny piece of what he said was true?

The FBI was furious with me for sending the money. They said it destroyed our credibility, that no one would take us seriously if we kept pursuing “conspiracy theories”.

I didn’t care. I would have sent a million dollars if I thought it would bring Johnny home.

1989: Paul Bonacci

Then, in 1989, something happened that changed everything.

A man named Paul Bonacci was sitting in a Nebraska prison, serving time for sexual assault. Through his lawyer, John DeCamp, he sent word that he had information about Johnny Gosch.

He said he’d been kidnapped as a child and forced into a sex trafficking ring. And he said he’d been forced to help kidnap Johnny.

John and I were skeptical. By this point, we’d dealt with so many liars, so many people trying to cash in on our tragedy. But we agreed to meet with him.

Paul told us things—specific things—that made my blood run cold.

He described Johnny’s birthmark on his chest. Okay, fine—that had been publicized.

But then he described a scar on Johnny’s leg. And a horseshoe-shaped scar on his tongue. And the way Johnny would stutter when he got nervous or upset.

None of that had ever been made public. Ever.

I looked at Paul Bonacci sitting across from me in that prison visiting room, and I knew—I knew—he was telling the truth.

He said Johnny had been held in Sioux City for several days after the kidnapping. He said he’d seen him again four years later in Colorado. He said the ring involved powerful people—businessmen, politicians, people who could make investigations disappear.

The police refused to believe him. They said his alibi put him in Nebraska the morning Johnny was taken.

But I believed him. I still believe him.

Because Paul Bonacci knew things about my son that only someone who’d met him could possibly know.

May 23, 1985: Testifying Before Congress

In May 1985, I was asked to testify before the Senate Subcommittee on Children, Family, Drugs and Alcoholism.

Senator Paula Hawkins was chairing the hearing on missing children, and she wanted to hear from parents who’d been through the nightmare. John Walsh—whose son Adam had been murdered three years earlier—was testifying too.

I sat in that hearing room in Washington, D.C., and I told them everything.

I told them about the seventy-two-hour waiting period that cost us critical time in finding Johnny. I told them about the police who dismissed us, who treated my son like a runaway instead of a kidnapping victim. I told them about the lack of coordination between agencies, the missing databases, the incompetence that let predators snatch children off the street with impunity.

My voice didn’t shake. I didn’t cry.

And when I finished, things started to change.

Iowa passed the Johnny Gosch Bill in 1984, requiring immediate investigation of missing children cases where foul play might be involved. Seven other states followed.

The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children was established.

Johnny’s picture—along with Eugene Martin’s—appeared on milk cartons across America. They were the second and third children to be featured that way.

I had turned my grief into action. I had made sure that no other parent would face what John and I faced: a system that didn’t care, that didn’t act, that let children disappear without consequence.

But none of it brought Johnny home.

The Marriage That Couldn’t Survive

People always ask me what happened between John and me.

We divorced in 1993, eleven years after Johnny disappeared.

The simple answer? Grief destroyed us.

We handled Johnny’s disappearance differently. I needed to act—to investigate, to speak out, to fight. John needed space, normalcy, time to process.

I spent every spare dollar on private investigators. He thought I was chasing shadows.

I believed Paul Bonacci. He didn’t.

I kept searching, kept pushing, kept refusing to give up. And somewhere along the way, we stopped being partners and started being strangers living in the same house.

The night I told John I wanted a divorce, we sat at the kitchen table—the same table where we used to eat breakfast with Johnny—and we cried.

“I love you,” he said quietly. “But I can’t do this anymore. I can’t keep living like this.”

“I know,” I whispered.

We’d both been shattered by the same tragedy, but the broken pieces of us no longer fit together.

After the divorce, John remarried. So did I. We remained civil, even defending each other over the years when people suggested one of us might have been involved in Johnny’s disappearance.

But the truth is, we never really spoke again. Not in any meaningful way.

Johnny’s kidnapping didn’t just steal my son. It stole my marriage too.

The Darkest Years

There were years—so many years—when I didn’t want to be alive anymore.

I’d wake up in the morning and the weight of it would crush me before I even opened my eyes. Johnny is gone. Johnny is gone. Johnny is gone.

I worked three jobs just to keep the investigation going. I’d come home exhausted, fall into bed, and lie awake all night thinking about where he might be, what might be happening to him.

People don’t understand what it’s like to live in limbo. If your child dies, you grieve, you bury them, you eventually—eventually—find a way to move forward. But when your child is missing? You exist in a state of perpetual agony.

Is he alive? Is he dead? Is he suffering? Does he remember me? Does he think I abandoned him?

Every birthday, every Christmas, every milestone he should have reached, I wondered. Wondered if he was celebrating somewhere. Wondered if he was thinking of me the way I was thinking of him.

The not-knowing is a special kind of hell.

And through it all, people watched. People judged. They called me obsessed, paranoid, delusional. They said I should move on, let it go, accept that Johnny was gone.

But how? How do you let go of your child?

The Visit, The Photos, and The Hope That Won’t Die

March 1997: The Night That Changed Everything

It was around 2:30 in the morning when I heard the knock on my apartment door.

I’d been living alone in West Des Moines for a few years by then—John and I had divorced in 1993, and I’d remarried, though that marriage wouldn’t last either. I was in my late forties, and I hadn’t slept well in fifteen years.

The knock was soft. Tentative. Like whoever was on the other side was afraid to be heard.

I pulled on my robe and walked to the door, my heart already pounding. Nobody comes to your door at 2:30 in the morning with good news.

I looked through the peephole and saw two men standing in the hallway. One was tall, thin, unfamiliar. The other—

God.

The other one had Johnny’s eyes.

My hands were shaking so badly I could barely unlock the door. When I finally got it open, I just stood there, frozen, staring at the young man in front of me.

He was twenty-seven years old now. His hair was long—shoulder-length, straight, dyed black. He was wearing jeans, a shirt, and a coat because it was cold that night in March. He was taller than I’d imagined, broader in the shoulders, with lines around his eyes that shouldn’t have been there yet.

But it was him. I knew it was him.

“Johnny?” I whispered.

He didn’t answer. He just opened his shirt and showed me the birthmark on his chest—the same one I’d seen a thousand times when he was a baby, when I’d change his diaper or give him a bath.

I started crying then. I couldn’t help it.

“Can we come in?” he asked quietly.

I stepped back and let them inside. The other man—I never learned his name, never saw him again—stood near the door like a guard while Johnny and I sat on the couch.

We talked for about an hour and a half. Maybe longer. Time felt strange that night, like it was stretching and compressing all at once.

But here’s the thing that broke my heart: Johnny kept looking at the other man before he spoke, like he was asking permission. And whenever the conversation got too specific—where he was living, how to reach him, who had taken him—the other man would shake his head slightly and Johnny would go quiet.

He told me he’d been taken by a ring. That he’d been used—God, the word he used—”used” for years. He said when he got too old, they cast him aside. He said he was living under a new identity now, that it wasn’t safe to come home, that if I called the police I’d be putting him in danger.

“I can’t stay,” he said. “I just—I needed to see you. I needed you to know I’m alive.”

“Johnny, please—”

“I can’t, Mom.”

That word. Mom. I hadn’t heard it in fifteen years.

I wanted to grab him. I wanted to lock the doors and refuse to let him leave. I wanted to call the police, the FBI, everyone—but he’d made me promise I wouldn’t.

“If you call them, I’ll disappear again,” he said. “And you’ll never see me again.”

So I didn’t call. I let my son walk out of my apartment and back into the darkness, and I kept my mouth shut for two agonizing years.

The Doubt That Haunts Me

John didn’t believe it was really Johnny.

When I finally told him about the visit in 1999—I testified about it during Paul Bonacci’s civil suit—he said it was probably another scam artist. Someone who knew enough about Johnny to fake it. Someone who wanted to hurt me.

Maybe he was right. God knows I’ve been fooled before.

But I don’t think so. I felt it. A mother knows her child.

The police said there was no proof. The FBI said I couldn’t corroborate any of it. Skeptics said I was delusional, grasping at straws, unable to accept that my son was probably dead.

And some nights—some long, dark nights when I can’t sleep—I wonder if they’re right. I wonder if grief has twisted my memory, if I’ve turned a desperate hope into a false memory.

But then I remember the way he looked at me. The way he said “Mom.”

And I know it was him.

August 27, 2006: My Birthday Gift

On August 27, 2006—my birthday—I found an unmarked envelope on my doorstep.

I wasn’t expecting anything. I’d stopped expecting surprises years ago. But there it was, just sitting there, no return address, no postage.

I brought it inside and opened it.

Inside were three photographs.

The first was a black-and-white photo of a boy lying on a bed. His mouth was gagged. His hands and feet were tied. He was wearing sweatpants—the same sweatpants Johnny had been wearing the morning he disappeared.

I couldn’t breathe.

The second photo was in color. It showed three boys, all bound and gagged, all looking terrified.

The third photo was of a man—possibly dead—with something tied around his neck.

I sat on my floor holding those photos, and I felt something inside me crack open all over again.

“This is him,” I whispered to the empty room. “This is my baby.”

I called the police immediately. The Iowa Division of Criminal Investigation took the photos and started analyzing them. They wanted to determine if they were authentic, where they came from, whether there were any fingerprints or DNA.

And then, a week later, an anonymous letter arrived at the Des Moines Police Department.

The letter said the photos were a “reprehensible joke” being played on a grieving mother. It said the pictures were from Tampa, Florida, around 1979 or 1980—before Johnny even disappeared—and showed kids doing an “escape challenge”.

A detective named Nelson Zalva confirmed he’d investigated those photos in the late 1970s and found no evidence of a crime.

But here’s what haunts me: Detective Zalva couldn’t provide proof that it was the same photo. And according to the 2014 documentary Who Took Johnny, only three boys in those pictures were ever identified by law enforcement.

The fourth boy—the one I believe is Johnny—was never identified.

2025: Still Searching

I’m in my late seventies now. Johnny would be fifty-five years old.

I run a private Facebook group called “Official Johnny Gosch Group” with about 3,500 members. People ask me questions—hundreds of them, thousands—and I answer as best I can.

Some people think I’m crazy. They think I’ve spent forty-three years chasing ghosts and conspiracy theories. They point to my associations with controversial figures, my belief in networks and rings that sound too big, too organized, too impossible to be real.

Maybe they’re right. Maybe I am crazy.

But I’ve also been proven right about so many things over the years. The seventy-two-hour waiting period that I fought against? Gone. The Johnny Gosch Bill made sure of that. The lack of a national database for missing children? Fixed. The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children exists because of parents like me, parents who refused to shut up and go away.

And the trafficking rings that everyone said didn’t exist? We know now that they’re real. We’ve seen case after case—Jeffrey Epstein, Larry Nassar, the Catholic Church scandals—proving that powerful people do abuse children, and systems do protect them.

So maybe I’m not crazy. Maybe I was just early.

What I Want You to Know

If you’re reading this, I need you to understand something: I don’t expect you to believe everything I believe.

I don’t expect you to think the 1997 visit was real. I don’t expect you to look at those photos and see Johnny the way I do.

But I do expect you to understand why I believe. Why I’ve spent forty-three years fighting.

Because what else was I supposed to do? Give up? Accept that my son was gone and move on with my life?

I couldn’t. I can’t.

People say I’m obsessed. They say I’ve let Johnny’s disappearance consume my entire life. And they’re right. It has.

But wouldn’t you? If it were your child?

Every parent says they’d do anything for their kids. They say they’d move heaven and earth, that they’d never stop searching. But most parents never have to prove it.

I did.

For forty-three years, I’ve proven it every single day.

A Message to Johnny

Johnny, if you’re out there somewhere—if you’re reading this, if someone shows it to you—I want you to know something.

I never stopped looking for you. Not for one day, not for one hour. Every choice I made, every interview I gave, every fight I picked with the police or the FBI or anyone who stood in my way—it was all for you.

I’m sorry I couldn’t protect you that morning. I’m sorry I stayed in bed instead of walking you to your paper route. I’m sorry the system failed you, that the people who should have found you didn’t try hard enough, didn’t care enough.

I’m sorry for everything you went through. Everything you’re still going through.

But I want you to know: you are loved. You have always been loved. And if you can never come home, if you can never be safe enough to see me again, I understand.

Just know that I’m here. I’m still here.

And I’ll be here until the day I die.

My Legacy

I know what people will say about me when I’m gone.

They’ll say I was the crazy mother who couldn’t let go. The woman who saw conspiracies everywhere, who believed con men and scammers, who spent her entire life chasing a ghost.

But they’ll also say this: I changed the system.

Because of Johnny—because of what happened to him and what I did afterward—children can’t disappear into a seventy-two-hour void anymore. Parents don’t have to wait three days to report their child missing. There are databases, protocols, Amber Alerts, systems in place to find kids before it’s too late.

Eugene Martin’s mother and I—we fought for that. Marc Allen’s family fought for that. Adam Walsh’s father, John, fought for that.

We took our grief and our rage and we turned it into something that saves lives.

That’s my legacy.

Not the conspiracy theories. Not the 1997 visit or the 2006 photos or any of the controversial things I’ve believed over the years.

My legacy is this: no other parent will ever have to go through what I went through.

And if that’s all I accomplish in this life—if that’s the only thing I’m remembered for—then maybe all this pain meant something after all.

The Hope That Won’t Die

People ask me if I still think Johnny’s alive.

Yes. I do.

I know it’s been forty-three years. I know the odds. I know what statistics say about missing children who aren’t found in the first forty-eight hours.

But I also know this: Elizabeth Smart was found after nine months. Jaycee Dugard was found after eighteen years. The three women in Cleveland—Amanda Berry, Gina DeJesus, Michelle Knight—were found after a decade.

Miracles happen.

And until someone proves to me beyond any doubt that my son is dead, I will keep hoping.

I will keep searching.

I will keep fighting.

Because that’s what mothers do.

We don’t give up. We don’t stop. We don’t let go.

And someday—maybe not today, maybe not tomorrow, but someday—I believe I’ll see my son again.

Maybe in this life. Maybe in the next.

But I’ll see him.

And when I do, I’ll hold him and I’ll tell him what I should have told him that September morning in 1982, before he walked out the door with his red wagon and his little dog.

“I love you, Johnny. I love you so much. And I am so, so sorry.”

News

The Face Hidden in Every Frame: The Jennifer Kesse Mystery

The Morning That Changed Everything A Life Built with Purpose The January sun rose over Orlando, Florida, painting the sky…

“What Really Happened to the Springfield Three? Inside America’s Greatest Unsolved Mystery”

The Last Normal Night The summer air hung thick and sweet over Springfield, Missouri, on the evening of June 6,…

After 46 Years, DNA Finally Whispered His Name: The Carla Walker Murder That Refused to Stay Cold

A Valentine’s Dance, A Stolen Life, and Nearly Half a Century of Waiting for Justice February 17, 1974, started like any other Sunday…

After 46 Years, DNA Finally Whispered His Name: The Carla Walker Murder That Refused to Stay Cold

A Valentine’s Dance, A Stolen Life, and Nearly Half a Century of Waiting for Justice February 17, 1974, started like any other Sunday…

The Hart Family Tragedy: The Perfect Instagram Family That Hid a Decade of Horror Before Driving Off a Cliff

When “Free Hugs” Became a Funeral Shroud: The Untold Story America Needs to Hear On March 26, 2018, a German…

“Kidnapped in Cleveland: The True Story of Three Women Who Refused to Give Up Hope After a Decade in Hell”

The morning of August 23, 2002, started like any other desperate morning in Michelle Knight’s life. She stood in…

End of content

No more pages to load