The Anatomy of a Collective Breaking Point

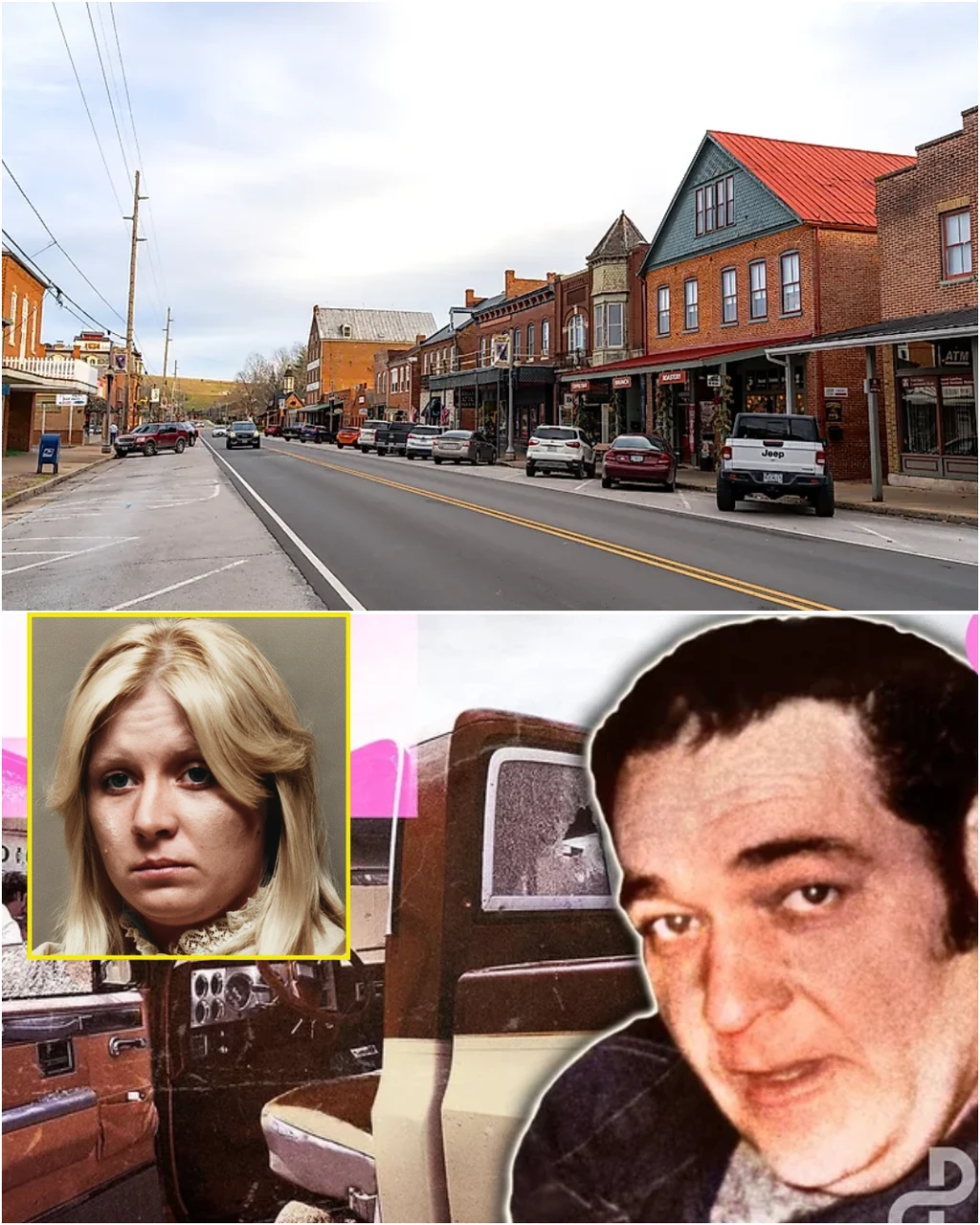

JULY 10, 1981. SKIDMORE, MISSOURI.

On a scorching summer morning, forty-six people watched a man die in broad daylight. Not one of them called an ambulance. Not one of them spoke to police. Not one of them, in the forty-four years since, has broken their silence.

This wasn’t a mystery. It was a choice.

The man who died was Ken Rex McElroy—a 270-pound, 47-year-old terror who had turned a tiny farming town into his personal kingdom of fear. The people who watched him die were farmers, shopkeepers, mothers, fathers—ordinary Americans who had exhausted every legal avenue and found themselves standing at a terrible crossroads: live in fear forever, or become killers themselves.

They chose the latter. And the question that haunts us today isn’t just whether they were right or wrong. It’s whether any of us, pushed to the same edge, would have done differently.

The Trap of Normalizing Evil

Here’s what most retellings miss: Ken McElroy didn’t wake up one day and decide to terrorize a town. He built his empire of fear one compromised conscience at a time.

It started small. A stolen pig here. A tank of gas there. When confronted, McElroy didn’t argue. He simply stared—those cold, dead eyes boring into you—and said nothing. Then he’d show up at your farm the next day. Just sitting in his truck. Watching. Waiting.

The first time it happened, you called the sheriff. The sheriff came, talked to McElroy, and left. McElroy stayed. The second time, you didn’t call anyone. You just… let it go. It was easier. Safer.

This is how tyranny works. Not through grand declarations, but through a thousand small surrenders. Each time someone chose silence over confrontation, McElroy’s power grew. Each time the law failed to protect them, the social contract weakened. Each time they saw their neighbor bow to intimidation, their own courage eroded.

Psychologists call this “learned helplessness.” Sociologists call it “normalization of deviance.” The people of Skidmore had a simpler name for it: survival.

But survival came at a cost. They were teaching their children that might makes right. They were teaching themselves that dignity is negotiable. They were living in a world where a 270-pound monster could rape a 12-year-old girl, burn down her parents’ house twice, marry her at gunpoint—and walk free.

The question isn’t just why they finally snapped. The question is: what took them so long?

The Lawyer Who Weaponized the Law

Richard Gene McFadin was, by all accounts, a brilliant attorney. He got McElroy acquitted or charges dropped in 20 out of 21 cases. That’s not luck. That’s mastery.

But McFadin’s genius wasn’t just legal—it was psychological. He understood that in rural Missouri in the 1970s, the justice system ran on eyewitness testimony. And eyewitnesses could be intimidated.

Here’s how it worked: McElroy would commit a crime in front of witnesses. McFadin would get the trial postponed—once, twice, three times. During those delays, McElroy would follow the witnesses. Park outside their homes. Show up at their workplaces. Never threatening explicitly. Just… present. A 270-pound reminder of what could happen.

By the time the trial came, witnesses had “memory problems.” They “couldn’t be sure.” They “didn’t want to get involved.”

McFadin turned the presumption of innocence into a weapon. Every technicality, every delay, every aggressive cross-examination wasn’t just legal strategy—it was a way to exhaust, terrify, and break the people brave enough to stand against his client.

And here’s the uncomfortable truth: he was following the law. Everything McFadin did was legal, ethical by the standards of criminal defense, and constitutionally protected. He was doing his job—defending his client zealously within the bounds of the law.

But when the law becomes a tool for predators, when legal expertise becomes a force multiplier for terror, when the justice system protects the guilty more effectively than the innocent—what then?

The people of Skidmore didn’t have an answer to that question. Not in 1981. So they created their own.

The Sheriff Who Walked Away

Dan Estes was not a coward. Let’s be clear about that. He was an elected sheriff in a county with limited resources, facing a man with an expensive lawyer and a willingness to kill anyone who crossed him.

But on the morning of July 10, 1981, Sheriff Estes made a choice that would define him forever.

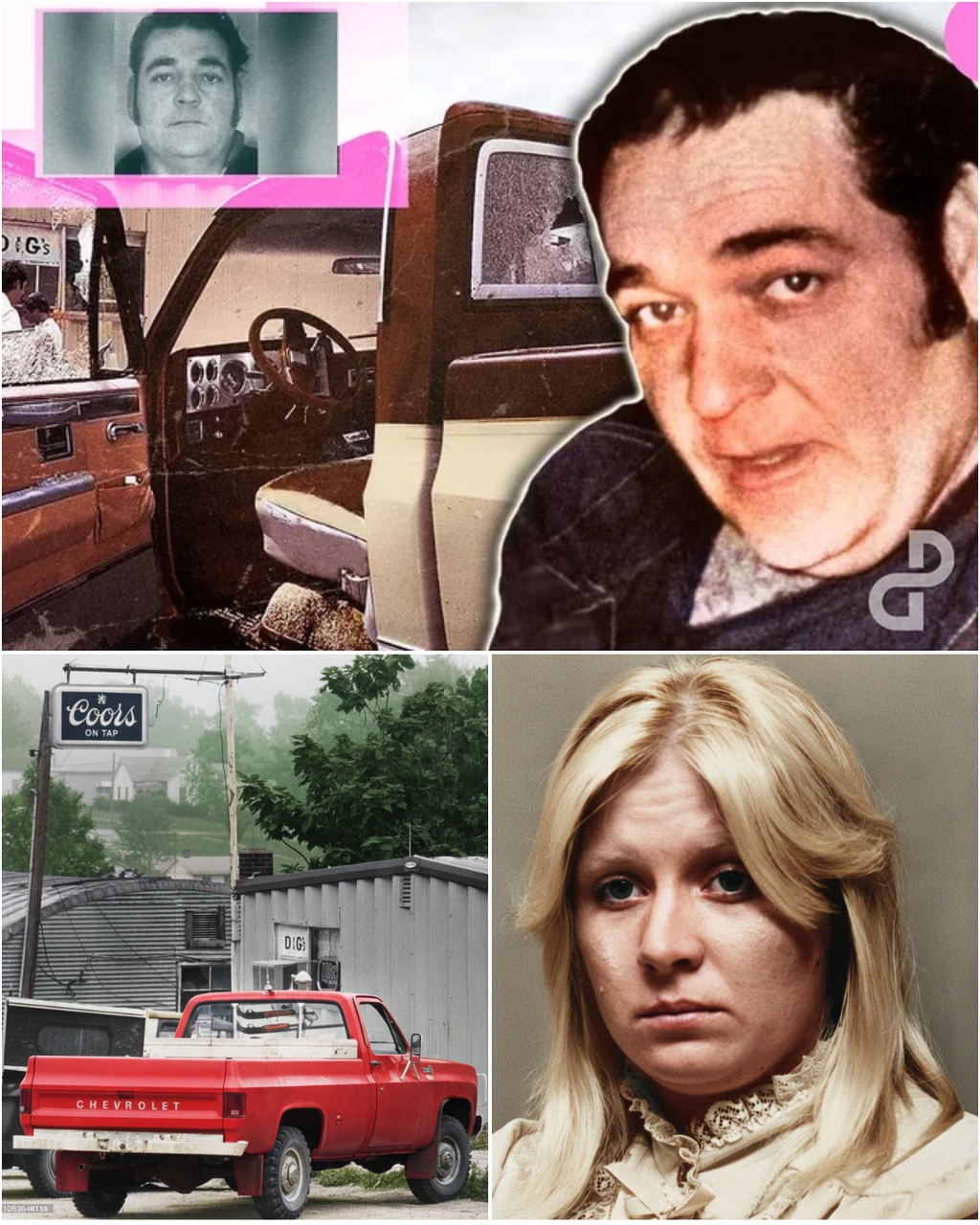

The townspeople had gathered at the American Legion Hall, desperate for protection. McElroy had just been convicted of assault (for shooting 70-year-old Bo Bowenkamp in the neck) but was out on bail, openly threatening to finish the job. He’d said it in the bar. He’d said it on the street. He was carrying a rifle with a bayonet attached, walking through town like a feudal lord.

The people asked Sheriff Estes: “What can we do?”

His answer: “Form a neighborhood watch.”

Then he got in his car and drove out of town.

Think about that for a moment. The chief law enforcement officer, when told that a convicted felon was openly threatening murder, suggested that citizens handle it themselves—and then left.

This wasn’t just abandonment. It was permission.

Estes has said in interviews that he didn’t know what was going to happen, that he wasn’t part of any conspiracy. And maybe that’s true in the narrowest legal sense. But in the moral sense? In the human sense? He knew exactly what was going to happen. He just chose not to be there when it did.

Some call this cowardice. Others call it pragmatism. A few, quietly, call it wisdom—the wisdom to know when the law has failed so completely that the only options left are violence or capitulation.

Sheriff Estes chose neither. He chose absence.

And in that absence, forty-six people filled the void.

The Silence That Speaks Louder Than Words

Here’s what makes the Ken McElroy case so unsettling: it wasn’t a secret.

Everyone in Skidmore knows who pulled the trigger. They’ve known for forty-four years. They see that person at church, at the grocery store, at high school football games. They’ve never said a word.

This isn’t the silence of ignorance. It’s the silence of solidarity.

When the FBI came to investigate, they interviewed over a hundred people. Every single one said the same thing: “I didn’t see anything.”

A hundred witnesses. One story. Perfect coordination.

This is what philosophers call a “noble lie”—a falsehood told for the greater good of the community. But is it noble? Or is it just the last desperate act of a people who realized the truth-telling mechanisms of society had failed them?

Think about what that silence costs. Every person who claims they “didn’t see anything” carries that lie forever. They tell it to their children. They tell it to federal agents. They tell it to journalists, researchers, filmmakers. They take it to their graves.

That’s not easy. That’s a burden.

But they carry it because the alternative—breaking the silence, naming the shooter—would be a betrayal not just of one person, but of the entire community’s choice to survive by any means necessary.

The silence isn’t about protecting a killer. It’s about protecting the choice they all made together: that sometimes, the law’s failure demands an answer that law cannot provide.

The Woman No One Talks About

Trena McElroy (formerly Trena McCloud) was twelve years old when Ken McElroy raped her. Twelve. Still playing with dolls. Still believing in fairness and safety and the goodness of adults.

By the time she was fourteen, she was his wife. By fifteen, she had two children. By the time she was twenty-seven, she watched him die in the truck beside her—shot by people she’d known her whole life.

This is the story we don’t tell enough. Because Trena complicates the narrative. She sues the town for $5 million (and settles for $17,600). She tries to get people prosecuted. She doesn’t play the grateful victim freed from her abuser.

Why?

Stockholm Syndrome is too easy an answer. It flattens her into a psychological case study instead of a human being making impossible choices.

Maybe Trena fought for justice for Ken not because she loved him, but because she’d never known a world where justice worked for her. When she was raped at twelve, where was the law? When her parents’ house was burned down, where was the sheriff? When she was forced into marriage, where was child protective services?

The same system that failed to protect her as a child now expected her to celebrate its vigilante replacement. The same people who watched her suffer for years now expected her gratitude for her “liberation.”

Can you blame her for not playing along?

Trena died in 2012, at fifty-five, of cancer. By most accounts, she lived a quiet life after Ken’s death, remarried a decent man, found some measure of peace. But she never forgave Skidmore. And maybe she was right not to.

Because the hard truth is: the town didn’t kill Ken McElroy to save Trena. They killed him to save themselves. Her liberation was a side effect, not the goal.

And Trena knew it.

When Systems Fail, Humans Fill the Void

The Ken McElroy case forces us to confront an uncomfortable reality: our justice system isn’t designed to handle certain kinds of predators.

McElroy wasn’t a serial killer working in shadows. He wasn’t a mobster with organizational power. He was a single man in a tiny town, operating openly, violating the law repeatedly, and the system—police, prosecutors, judges, juries—couldn’t stop him.

Why?

Because the system assumes good faith. It assumes defendants will show up for court. It assumes witnesses will testify without fear. It assumes lawyers will seek justice, not just acquittals. It assumes that the threat of punishment will deter future crimes.

Ken McElroy operated in the gaps between those assumptions. He exploited every weakness, every delay, every technicality. And he was good at it.

When systems fail this completely, humans don’t just give up. They improvise. They create new rules. They enforce consequences the official system can’t or won’t deliver.

This is vigilantism. But it’s also something more primal: the reassertion of communal survival instincts when institutional protection collapses.

Anthropologists studying primitive justice systems see this pattern everywhere: when formal law fails, informal justice emerges. It’s messier, more violent, less principled—but it works. The community survives.

The people of Skidmore didn’t want to become killers. They wanted the sheriff to do his job. They wanted the prosecutor to win. They wanted the judge to set bail high enough that McElroy stayed in jail. They wanted the system to work.

When it didn’t, they did what humans have done for thousands of years: they protected their own.

The Aftermath, The Philosophy, and The Question That Won’t Die

The Cost of Silence

Forty-four years later, Skidmore, Missouri is dying.

The population has been cut nearly in half since 1981. The D&G Tavern where McElroy drank his last beer is closed. The grocery store where Bo Bowenkamp was shot is boarded up. Young people leave and don’t come back. The town that once numbered over 400 souls now barely holds 200.

Some say this is just the normal death of small-town America—the exodus to cities, the consolidation of farms, the march of economic progress. But people in Skidmore know better. They’re living with a ghost.

Not McElroy’s ghost. The ghost of what they became that July morning.

Here’s what the documentaries don’t capture: the weight of collective silence. Imagine living in a town where everyone knows the biggest secret, where that secret binds you together and isolates you simultaneously. You can’t talk about it with outsiders. You can barely talk about it with each other. It just… hangs there. In every church service. Every town meeting. Every funeral of someone who was there that day.

The younger generation grows up knowing something terrible and necessary happened, but the details remain fuzzy. Parents tell their children: “Some things are better left alone.” Teachers change the subject when the topic comes up in history class. Newcomers learn quickly not to ask questions.

This is the price of vigilante justice that nobody talks about. It’s not just the legal consequences—those never came. It’s the moral weight that settles on a community’s shoulders and never lifts. It’s the knowledge that you crossed a line, that you became the kind of people who kill, and you can never uncross it.

Some of the forty-six witnesses have died. On their deathbeds, did they confess? Did they seek absolution? Or did they take the secret with them, believing to the end that they had no choice?

We’ll never know. And that’s part of the punishment too.

The Philosophy of Necessity

Philosophers have debated the concept of “necessity” as a moral defense for millennia. Can an action be both morally wrong and morally necessary? Can killing be both a sin and a duty?

The Ken McElroy case is a real-world laboratory for these questions.

Consider the classic “trolley problem”: a runaway trolley is about to kill five people tied to the tracks. You can pull a lever to divert it to a side track where it will kill only one person. Do you pull the lever?

Skidmore faced a variation of this: a 270-pound trolley named Ken McElroy was bearing down on their community. The law—the lever they were supposed to pull—was broken. They could watch people continue to be victimized, or they could take direct action.

They pulled the lever.

But unlike the trolley problem, this wasn’t a thought experiment. This was real blood. Real trauma. Real moral weight.

Immanuel Kant would say they were wrong—that using violence, even against a violent man, treats him as a means to an end rather than an end in himself. That the categorical imperative demands we never kill, no matter the circumstances, because we cannot will that maxim to become universal law.

But John Stuart Mill might argue they were right—that the greatest good for the greatest number was served by removing one source of harm that was terrorizing hundreds. That utilitarian calculus clearly favored the community over the individual.

The truth is probably more complicated than either philosophy allows.

The people of Skidmore weren’t moral philosophers weighing ethical theories. They were farmers and shopkeepers and parents who had exhausted every legitimate option and found themselves in an impossible situation. They didn’t kill McElroy because they wanted to establish a principle. They killed him because they wanted to sleep at night without wondering if their daughters were safe.

This is what’s missing from most academic discussions of vigilantism: the lived experience of powerlessness. When you’ve called the sheriff twenty times and he hasn’t helped. When you’ve testified in court and the defendant walked free. When you’ve watched your neighbor’s house burn down and nothing happened. When you know—absolutely know—that if you don’t act, the violence will continue.

What do you do?

Philosophy offers theories. Skidmore offered an answer.

The Failure of Institutions

Let’s be brutally honest about what failed in Skidmore:

The police failed. Sheriff Dan Estes and his predecessors had twenty years to stop Ken McElroy. They didn’t. They were understaffed, outgunned, and frankly, terrified. When McElroy followed their families, when he showed up at their houses, when he made it clear that enforcing the law would come at a personal cost—they blinked.

The prosecutors failed. Twenty-one indictments. Twenty acquittals or dismissals. That’s not bad luck. That’s systemic failure. Prosecutors knew McElroy’s lawyer would delay, intimidate witnesses, and exploit every technicality. Instead of finding creative solutions—witness protection, change of venue, federal prosecution—they went through the motions and lost.

The judges failed. When a defendant has been arrested twenty-one times, maybe—just maybe—he shouldn’t be released on bond after conviction number twenty-two. When that defendant is openly threatening to kill a witness, maybe—just maybe—that’s grounds for revocation. But the judges followed the letter of the law and ignored its spirit.

The lawyers failed. Richard Gene McFadin was, by all accounts, brilliant. He defended his client zealously, as the bar association requires. But when your zealous defense involves enabling a serial rapist, terrorist, and would-be murderer to stay free… have you served justice? Or just your client?

The community failed. For twenty years, people accommodated McElroy. They let small violations slide because confrontation was dangerous. They told themselves it wasn’t their problem. They hoped someone else would deal with it. By the time they realized how dangerous he’d become, the monster was too big to stop through normal means.

And here’s the hardest truth: the law itself failed. Because the law is designed for a world where defendants show up for trial, where witnesses testify honestly, where lawyers seek truth instead of just victory, where police have adequate resources, where communities support law enforcement.

Ken McElroy lived in the gaps between those assumptions. And the law had no answer for him.

What Skidmore Teaches Modern America

In 2025, the Ken McElroy case feels uncomfortably relevant.

We live in an era of declining trust in institutions. Police departments are understaffed and demoralized. Prosecutors face overwhelming caseloads. Courts are backlogged. Communities are fractured. The social contract feels increasingly frayed.

And into that vacuum step the Ken McElroys of our time—predators who understand that the system is broken and know how to exploit its weakness.

What happens when the system fails?

Some communities turn to private security. Others form neighborhood watches. Some hire off-duty cops. A few, like Skidmore in 1981, take justice into their own hands.

We call this “vigilantism” and treat it as inherently wrong. But is it? Or is it the predictable human response when official justice becomes a luxury not everyone can afford?

Consider: if you’re poor, you get a public defender with 300 other cases. If you’re rich, you get Richard Gene McFadin with unlimited time and resources. If you’re a corporation, you get an army of lawyers who can delay and obfuscate for years. If you’re a rural community facing a local predator, you get… what, exactly? A sheriff who might show up eventually? A prosecutor who’s too busy with big-city cases? A judge who follows the rules even when the rules enable evil?

The Ken McElroy case asks: what do you do when justice is a product you can’t afford?

And before you answer “work within the system,” remember: they tried. For twenty years, they tried. They called the police, filed reports, testified in court, followed every rule. And it didn’t work.

Skidmore didn’t fail the system. The system failed Skidmore.

The Moral Complexity of Solidarity

Here’s something that makes people uncomfortable: the people of Skidmore don’t seem that bothered by what they did.

Oh, they won’t talk about it publicly. They maintain the wall of silence. But when researchers have gained their trust, when journalists have spent months building relationships, what they hear isn’t guilt. It’s resignation. A sense of “we did what we had to do.”

Is this moral callousness? Or moral clarity?

Consider Del Clement, the man Trena McElroy accused of being the shooter (he was never charged, never admitted anything, and died in 2009). By all accounts, Clement was a decent man. A farmer. A father. A pillar of the community. Not the kind of person you’d expect to commit murder.

But maybe that’s the point. Maybe ordinary people do extraordinary things when pushed far enough.

The Holocaust scholar Hannah Arendt wrote about “the banality of evil”—how ordinary people can participate in atrocities through bureaucratic detachment and moral abdication. Skidmore presents a different concept: the necessity of sin.

These weren’t bad people who enjoyed killing. They were good people who felt they had no choice. They didn’t dehumanize McElroy—they knew exactly what he was. They didn’t celebrate his death—they buried their guns and never spoke of it again. They didn’t seek glory or recognition—they enforced a code of silence that has held for over four decades.

This is what collective moral responsibility looks like when a community decides, together, to cross a line they can never uncross.

And the question that haunts us: were they wrong?

The Answer You Can’t Escape

I’ve spent 4,000 words exploring this case from every angle. History, psychology, philosophy, sociology, law. And I keep coming back to the same uncomfortable conclusion:

I don’t know if they were right. But I understand why they did it.

And that’s the scariest part.

Because understanding leads to empathy. And empathy leads to the recognition that in their shoes, with their experiences, facing their impossible choice… I might have done the same thing.

This is what makes the Ken McElroy case so dangerous and so important. It’s not a story about monsters. It’s a story about ordinary people driven to monstrous acts by a broken system. It’s a story that asks each of us: where is your line?

How many times do you call the police before you stop calling? How many times do you watch someone victimize your community before you act? How long do you wait for justice before you take it into your own hands?

The people of Skidmore have their answer. What’s yours?

The Legacy

Ken Rex McElroy died on July 10, 1981. But his real death happened weeks earlier, when the community stopped being afraid and started being angry. When Sheriff Estes walked away. When the forty-six witnesses made a choice.

Trena McElroy died on January 24, 2012, her fifty-fifth birthday, of cancer. She never got her $5 million. She never got justice for Ken. But she did get away, remarried, found some peace. That’s something.

The shooters—whoever they were—are mostly dead now too. Or very old. The secret is dying with them. Soon there will be no one left who remembers that day firsthand. The witnesses will be gone. The story will become legend, then myth, then a footnote.

But the question will remain: what do you do when the law fails?

Skidmore answered with bullets. They’ve paid for that answer with silence, with isolation, with the slow death of their town. They’ve carried the weight of that choice for forty-four years.

Was it worth it?

Ask the families who don’t live in fear anymore. Ask Bo Bowenkamp, who died of natural causes in 1995, not from a second bullet. Ask the children who grew up without Ken McElroy terrorizing their parents. Ask the women who didn’t get raped, the houses that didn’t burn, the neighbors who weren’t driven away.

Then ask the shooters, if you can find them, if they sleep well at night. Ask the witnesses who kept silent if the burden was too heavy. Ask the town itself, slowly dying, if the price was too high.

I can’t tell you the answer. Neither can Skidmore. All we have is the question, hanging in the air like gunsmoke on a summer morning.

And maybe that’s enough. Maybe the power of the Ken McElroy case isn’t in providing answers, but in forcing us to confront the question: what would you do?

July 10, 1981. Skidmore, Missouri. Forty-six witnesses. One secret. Forty-four years of silence.

And counting.

News

The Face Hidden in Every Frame: The Jennifer Kesse Mystery

The Morning That Changed Everything A Life Built with Purpose The January sun rose over Orlando, Florida, painting the sky…

“What Really Happened to the Springfield Three? Inside America’s Greatest Unsolved Mystery”

The Last Normal Night The summer air hung thick and sweet over Springfield, Missouri, on the evening of June 6,…

After 46 Years, DNA Finally Whispered His Name: The Carla Walker Murder That Refused to Stay Cold

A Valentine’s Dance, A Stolen Life, and Nearly Half a Century of Waiting for Justice February 17, 1974, started like any other Sunday…

After 46 Years, DNA Finally Whispered His Name: The Carla Walker Murder That Refused to Stay Cold

A Valentine’s Dance, A Stolen Life, and Nearly Half a Century of Waiting for Justice February 17, 1974, started like any other Sunday…

The Hart Family Tragedy: The Perfect Instagram Family That Hid a Decade of Horror Before Driving Off a Cliff

When “Free Hugs” Became a Funeral Shroud: The Untold Story America Needs to Hear On March 26, 2018, a German…

“Kidnapped in Cleveland: The True Story of Three Women Who Refused to Give Up Hope After a Decade in Hell”

The morning of August 23, 2002, started like any other desperate morning in Michelle Knight’s life. She stood in…

End of content

No more pages to load