On a late night in 1990, under the golden lights of The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson, a young ventriloquist from Dallas stepped into television history—not with fireworks, but with a puppet named Peanut and a jalapeño on a stick.

The crowd didn’t know what to expect. Carson, the kingmaker of late-night comedy, had seen everything—from animal tricks to Elvis impersonators. But what Jeff Dunham brought was different. It wasn’t just a ventriloquist act. It was a full-blown personality parade—with sarcasm, absurdity, and timing so sharp it could slice through silence.

Peanut was the first to speak. Or rather, scream. A blur of purple fur, a mop of wild hair, and a voice that sounded like a helium balloon had an attitude problem. “Why do I look like this? Blame him!” Peanut shouted, jerking his thumb at Dunham, igniting laughter from the crowd.

From there, it spiraled—in the best way. The banter between Dunham and Peanut was fast, sharp, and chaotic. It felt improvised, alive. Every punchline landed like a drumbeat. And just when the audience thought they’d seen it all, a new character popped out: José Jalapeño… on a stick.

Yes, a jalapeño. With an accent. Talking about fear, Taco Bell, and the perils of being a pepper in America.

“Do you like your job?” Dunham asked.

“Si… but only when no one tries to eat me,” José replied, deadpan, drawing howls of laughter.

It was absurd. But it worked. The characters weren’t just puppets—they were personalities. They had backstories, quirks, even grudges. At one point, Peanut teased José for being immobile. José, in return, lamented his fate: “Stuck on a stick, and no one asked me.”

The brilliance wasn’t just in the jokes. It was how Dunham channeled multiple voices, rhythms, and emotions without ever breaking. The transitions between characters felt like a three-person dialogue in one body—and the audience couldn’t get enough.

Then came the worm. Yes, a worm on a stick. Soft-voiced, sweet, and drunk on well water. “I’ve been down in the cellar too long,” the worm muttered, slurring just enough to make it hilarious but not inappropriate. The innocence of the character clashed with the absurdity of its existence—and that’s what made it brilliant.

But Dunham wasn’t done.

Midway through, the conversation took a personal turn. He talked about growing up in Dallas, dreaming of big stages. He spoke about building his own helicopter—as casually as if he’d built a Lego set. And then he introduced Walter, the grumpy old man who hated everything.

Walter, with arms folded and a permanent scowl, instantly became the voice of every annoyed grandparent. “These people today,” he growled, “can’t do anything without Wi-Fi.” The crowd roared. Walter was every grump you’ve ever met, but funnier.

By the end of the performance, it wasn’t just a comedy act—it was a showcase of what ventriloquism could be. Not a gimmick, not a party trick, but a medium for real character-driven humor. Johnny Carson’s nod said it all.

That night, America didn’t just laugh—they discovered a new voice. Or rather, several voices—all coming from one impossibly talented man and the puppets that lived in his suitcase.

Three decades later, that moment still echoes—not just as the birth of Jeff Dunham’s TV career, but as the night when a talking jalapeño, a hyperactive purple creature, a drunk worm, and an angry retiree stole the spotlight from every human in the room.

News

My Daughter Kicked Me Out After Winning $10 Million, But She Never Noticed The Name On The Ticket.

You’ll never get a scent of my money, Dad. Not one. The door slammed shut. Those words from my…

I Inherited A Run-Down Old Garage From My Husband, But When I Walked In…

I never expected to spend my 68th birthday sleeping in an abandoned garage, surrounded by the scent of motor oil…

THE MILLIONAIRE’S TRIPLETS HAD ONLY ONE WEEK TO LIVE — UNTIL THEIR NEW NANNY DID THE IMPOSSIBLE

The Atlantic wind had a way of sounding like grief.It slipped through the pines and over the cliffs…

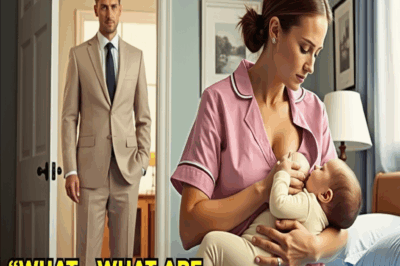

“A Widowed Millionaire Walked In on His Nanny Feeding His Baby—What Happened Next Shook the Whole Town”

The Cry in the Mansion The baby’s cry sliced through the marble halls like a siren trapped inside…

After Divorce I Became Homeless Until a Stranger Asked: ‘Are You Sophia? You Just Inherited $47M’

I’m Sophia Hartfield, 32, and I was elbow-deep in a dumpster behind a foreclosed mansion when a woman…

The Teacher Who Adopted Three Orphans — and How One Act of Kindness Changed Four Lives Forever

The Man Who Stayed After Class The rain came down like it always did in late November —…

End of content

No more pages to load