The porch light on Cedar Lane burned the way some people pray—softly, nightly, without witnesses.

Every evening at dusk, Helen Fowler twisted the brass knob on the old sconce beside her front door, and the bulb bloomed a gentle yellow that washed the steps and pooled on the walk. Some nights it looked brave, some nights tired; on good nights it was both. The maple in her yard—older than the mortgage, younger than her grief—threw dappled shadows on the white railing she and Frank had painted together the summer Jimmy Carter was elected.

Neighbors noticed. They always do, in towns where anyone can still name the last three owners of any house. Mrs. Walsh across the street called it “sweet.” The Culver boy said it was creepy “like a movie,” and then felt bad and carried Helen’s groceries out of contrition. Pastor John, passing on his evening walk, tipped his cap at the glow like it was a parishioner who’d kept the faith long enough to earn a nod.

People assumed what people assume: that Helen left the light on for a husband who was gone, because someone had to keep the welcome warm. They weren’t wrong. But the light wasn’t only for Frank, who died one April when the lilacs were out and the robins were bragging. It was for the years that stretched after. It was for the people she couldn’t reach and the parts of herself that sometimes wandered too far to find the door.

Her son Daniel thought it was a fire hazard. “Timers exist, Mom,” he said, standing in the kitchen with the earnest patience adults save for parents. “LED bulbs. Smart plugs. You can talk to a speaker and it turns on.”

“I’m not talking to a speaker,” Helen said, buttering toast with a knife that had cut more pies than arguments. “I’m talking to the dark.”

Daniel sighed, kissed the top of her head, and checked the date on the milk. “You talking back, at least?”

“Sometimes it listens,” she said. That made him smile the way he smiled at Emma when she claimed the moon followed their car home.

When Daniel left, she made tea and carried it to the porch. The light hummed quietly, like a cat who’d decided to like you. The street smelled of cut grass and grill smoke. A baseball game somewhere traveled across backyards on the easy evening air.

She didn’t set out to become a woman who measured days in light, but there she was. It began the spring Frank got sick, when nights felt like steep roofs and mornings like basements. The doctor said his heart had held longer than it had any right to. Frank called it a “failing engine,” put his big hand over hers, told her he’d done his best with the tools he had. He still went out to the garage to inventory bolts and mutter about carburetors none of their cars had possessed since 1992.

On hospital nights, Helen would return home to a quiet too clean to be kind. She’d turn the porch light on and stand beneath it, breathing the air she recognized, hearing the chime she’d bought at a county fair thirty years earlier. The light was something she could do. Brightness applied to darkness: a simple math she wasn’t equipped to use anywhere else.

The night Frank died, she left the light on until morning. She made coffee and didn’t drink it. She washed the two mugs anyway. She sat in the chair by the door where you can see the last corner a person rounds before they step inside—if they’re going to step inside. She kept sitting until the birds forgot to sing and then remembered, twice as loud.

After the funeral, people came and went, carrying covered dishes like apologies. They told stories about Frank that made her laugh and stories that made her cry and a few that made her roll her eyes in the privacy of her kitchen. The light stayed on. Folks noticed that, too. “It’s sweet,” Mrs. Walsh whispered, spooning baked ziti onto Helen’s plate. “It’s a lot,” said Carol from choir, then squeezed Helen’s hand as if to say A lot can be good. Daniel said nothing; he was cataloging practicalities, because somebody needed to.

Summer arrived all at once, the way it does when a long spring finally gives up. Daniel came every Sunday with his daughter, and the three of them walked to the farmer’s market where Helen bought tomatoes with more personality than the mayor. Emma, eight and steady, held her grandma’s hand tightly when they crossed Walnut. “Where does the light go in daytime?” she asked one noon under a white sun.

“It waits,” Helen said.

“What for?”

“Us,” Helen said, and squeezed back.

By August, old habits made new sense. Helen renewed the porch light bulb her husband used to change from a ladder, but she used the shorter, surer ladder Daniel had bought with a lecture about hips and gravity. She polished the brass plate with the careful devotion of a ritual. On the night of the town’s fireworks—so earnest and small they made everyone protective—she left the light on and watched from the porch, the little bursts of color reflected in the glossy paint of the front door.

That night Emma slept over. They made grilled cheese and sliced peaches. They watched a movie about a dog who went to space and found his way back home. Emma cried and tried not to, chin set like Daniel’s had been at eight. “It’s okay to cry when brave things happen,” Helen said, and handed her a napkin. Emma cried easily after that, the way bodies like to when they’ve been granted permission.

They were brushing their teeth when the phone rang—late enough to be worry. Helen answered because she still believed phones were for news you couldn’t hold long enough to carry down the steps. It was Carol from choir. “I know it’s not my business,” she began, making it exactly her business, “but Joseph Culver’s mother says he’s sleeping on Nick’s couch again. Dropped out of classes. Working nights. Drinking. You know how it starts.”

Helen knew a little about how it starts. Joseph had been in Emma’s Sunday School class three dozen years ago, which couldn’t be true and was. His father had thudded his fist on the back of a pew when the pastor mentioned forgiving overdue library books, a man with no humor and less patience. Joseph had mowed Helen’s lawn one summer when Frank’s back went out. He’d tried to refuse payment and then grown embarrassed by his refusal. He’d been a soft boy who didn’t know where to put his hands.

“Thank you for telling me,” Helen said, because that was what people said to close a call without closing their heart.

She lay awake listening to Emma breathe, and beyond that the town breathe. She thought of Joseph’s laugh when the mower had stalled, his face going pink, the way he kept glancing toward the porch to see if Frank was watching—a boy collecting approval the way others collect baseball cards. She thought of the dog movie and the way home is sometimes a light, and sometimes a voice saying your name like it’s a clean shirt.

In the morning she made pancakes and then made too many, on purpose. She wrote a note and stuck it to the bread box: Joseph—hotcakes on the porch—help yourself—H. She set a covered plate beneath the light like an offering. Then she went about her morning, sweeping the kitchen, losing and finding her glasses, getting dressed for the market. When she stepped back out, the plate was gone, the note folded into a square and tucked between the porch boards.

That afternoon she wrote another note. There’s lemonade in the fridge. Don’t let it boss you.

A week later, someone mowed her yard. The lines were imperfect and careful.

She found the folded square under the board again. Didn’t take the money, it read. Don’t be mad. Beneath, smaller: Thank you.

She laughed out loud in the empty living room, the ridiculous, honest laugh of someone who’d feared her world was done growing and found a new leaf on the same old tree. She pressed the square flat and slipped it into the recipe box, because all good things are worth saving under flour and sugar.

Joseph became the sort of presence small towns specialize in: visible in absence. He took the trash to the curb early on Mondays. He brought the paper to the porch when Helen slept late. He returned the serving dish she’d left at a potluck in 1999, which made her wonder where it had been living all this time and what it had seen.

Daniel disapproved of the ghost. “You can’t encourage strange men to lurk around your house,” he said with the exact tone Frank used to employ when asking why anyone would salt watermelon.

“He’s not strange,” Helen said. “He’s Joseph.”

“That’s what worries me.”

“Then be worried,” Helen said, not unkindly. “It’s a free country. The worrying.”

He exhaled sharply and put his hands on his hips like a man contemplating a rebellious stump. “At least get a door camera.”

“Joseph doesn’t need a camera,” Helen said. “He needs a porch.”

“Emmett Till needed a porch,” Daniel said, meaning to say the world is not gentle, forgetting for a second that his mother knew that.

Helen put her hand on his cheek. “And he needed adults who were braver than their fear.” She let her hand fall. “Frank would have sat with the boy. You know he would.”

Daniel knew. It did not soothe him. Love is harder when it comes with images of what could go wrong.

“You can’t fix everything,” he said, and sounded tired.

“I don’t intend to,” Helen said. “I’m running a light, not a hospital.”

That night she left a third note. If you get the urge to write, there’s paper in the mailbox. No one reads it unless you leave it.

Two days later she found a page with bent corners and sentences that tried hard to behave. Nights are loud, Joseph had written. If I close my eyes I can hear Nick’s TV and the highway and my dad. If I open them I only see the ceiling. I look at your light and my brain quiets down. I don’t even know if that makes sense. It does here. I’m trying to be good. It’s not easy when no one expects it from you.

Helen sat with that one a long time. She wrote a reply that said nothing and everything. Being good is mostly listening. Start with yourself. Don’t hush.

After that, the porch became a post office with only two customers. Notes went and came. Some were about nothing—the jay stole my peanut, peppermint tea tastes like toothpaste—and some were about the kind of nothing that’s really something—I didn’t drink yesterday, I slept last night, Thank you for the light.

When November came sobbing over the hills, the town tucked itself in earlier each evening. Helen’s light glowed brave against a dark that arrived too soon. Daniel bought her the timer anyway, put it on with a flourish. “Now you won’t forget,” he said.

“I don’t forget,” Helen said.

“Then it won’t hurt,” he said, smiling like he’d found a compromise.

For a week the timer worked. The light clicked on at 4:52 p.m., a precise kindness. On the eighth day the power flickered and the timer hiccuped itself into silence. At five-thirty Helen stepped onto the porch to find the world unlit, the knob cold under her thumb. “There now,” she said, and turned it. The bulb brightened like a sigh and held.

She didn’t tell Daniel. Some things you keep for the story they give you later.

On the first snow, she filled a thermos with cocoa and wrapped it in a towel and set it under the sconce with two cups. Below, on the steps, she placed a pair of gloves she had bought at the hardware store, thick ones with room to grow. She watched from the chair by the door, feeling foolish and pleased. At midnight the thermos was lighter. The gloves were gone. She slept well, and if she dreamed it was of Frank in the yard, shaking his head at a rake that didn’t deserve the scolding.

The next morning there was a note folded into the crack by the board again. I’ll pay you back, it said. For the cocoa, not the gloves. I’m keeping those forever.

Helen laughed in the kitchen and didn’t stop until the water in the kettle whistled for company.

Around Christmas, Joseph knocked for the first time. It was a tentative three-beat knock, the kind that doubles as apology. Helen opened the door because she rejected the idea that a woman at her stage of life ought to be afraid of a child who’d once fed her petunias too much water. He stood on the steps in a parka that was more color than fabric, hat tucked in a pocket, hair trying to be a plan.

“Hi,” he said, and then looked at his shoes. “I didn’t want to just write that I was leaving town for a bit. My cousin in Dayton has a couch. I’ll work at the warehouse. But I didn’t want you to think I ran away. It’s more like I’m walking in a direction.”

“I like walking,” Helen said.

He nodded. “Me too.”

She handed him a paper bag before he asked for anything, because grandmothers can smell hunger in the gaps between words. “Sandwiches,” she said. “And a thermos that doesn’t leak. I checked it.”

He took the bag with both hands, the way you take a baby you didn’t expect. “I can’t—”

“You can.”

His eyes found the light, which threw gold over the snow like paint. “I’ll write,” he said.

“Do,” she said. “Or don’t. Either way, the light will be here.”

He looked at her face like it contained instructions. “Why do you leave it on?” he asked.

She considered telling him the easy thing: For Frank. She considered the true thing: For me. Instead she said the widest thing: “Because darkness is lazy. You must give it chores.”

He laughed with his teeth and thanked her a hundred times without getting the number right, and then he left. Footsteps in the snow. Breath on the freeze. The bag under his arm like a mission. She watched until she couldn’t see him and then a little longer, in case seeing could be stretched by wanting.

Letters came. Not often, not orderly. On postcards of barns and bridges, in stamps that didn’t match, in handwriting that grew steadier with each attempt. I got the job. I saw a river frozen solid. I missed your light last night and looked at the exit signs on the highway instead. He never wrote I failed, but you can hear some songs even when they aren’t being played.

Spring lifted the dirt carefully and set down green. Helen planted zinnias because they were easy and showy, and because nobody could be sorry in the presence of zinnias. She tuned the old radio to the station Frank had loved, and when the ballgame droned about pitchers and promises she felt him moving around the house, not haunting so much as helping. She bought two lawn chairs—one for now, one for then—and set them on the porch like parentheses around a sentence.

Daniel visited every Sunday. Sometimes he brought Emma; sometimes Emma brought him. He checked the smoke detector and the basement for damp and the mailbox for mail that believed it was urgent. He tutted at the light and then kissed it with his eyes, which he’d deny.

“What are you writing?” he asked one morning, catching her at the table with pen in hand.

“Thank-you notes,” she said.

“For what?”

She smiled. “Light.”

He shook his head and grinned. The older he got, the more he resembled his father around the patience and his mother around the stubbornness. “Mom,” he said, softer. “You’re okay, right?”

“Right as rain,” she said. “Better, because rain leaves a mess.”

He let that stand and cut the lawn without insisting on stripes.

On a June evening that bragged it had invented light, Joseph returned. He didn’t knock. He stood at the end of the walk the way men do when they want permission to come home. Helen saw him from the chair, rose without haste, opened the door as if he’d just stepped out for milk.

“Hey,” he said. He was thinner and more himself, a paradox she hoped meant progress. He held a small box, not wooden but carefully taped.

“You’re late,” she said. “Supper waited.”

He laughed and wiped a surprise tear under the excuse of an itch. “I brought you something.”

She took the box. Inside lay a porch light bulb, the old kind with visible filament. On the side, in cautious blue ink: For when yours grows tired.

“Yours is better,” he said. “I found it at an antique place. The guy said no one buys them anymore because they don’t last. I thought, maybe that’s the point. Some things aren’t meant to last—just to keep trying.”

Helen held the bulb like a bird she trusted. “It’s perfect,” she said, and meant it. She set it gently on the table beside the paperweight Frank had made out of a smooth river stone. “Sit,” she said. “Tell me what the river said.”

He told her small stories that held big truths: a foreman who never smiled paper-thin until he did; a diner waitress who called everyone love without making it cheap; a night he nearly drank and didn’t. He didn’t tell her how hard nights can be when the brain is a house with all the lights on at once, but he didn’t have to. She recognized the shadows in the spaces between his sentences.

After he left she took the bulb to the porch and held it beside the glowing one. Hers hummed steady. The new one held stillness like a secret. She kept both.

The last letter he wrote came a month later and began with I think I’m okay. It ended with Thank you for leaving the light on even when you were tired. In the middle it said the one thing Helen had learned to hope for, not because it solved anything but because it made solving less lonely: If I come back, I’ll knock.

She folded that letter into halves and then halves again, and tucked it under the recipe for lemon bars. She made a tray and walked it next door to Mrs. Walsh, because joy, like grief, prefers company.

Here’s what no one tells you about porch lights, or maybe they do and you have to learn to hear it: they don’t exist to be noticed. They exist to be relied on. They don’t win awards. They fail, and then someone fixes them, and all the while the front door doesn’t lose its job.

On the anniversary of Frank’s death, Helen woke before the birds and sat beside the door with a notebook. She wrote his name in her neat schoolteacher script and then didn’t write anything else for a very long time. The light was still on from the night because she’d forgotten—or decided—not to turn it off. The room held its breath. The town shifted in sleep.

When coloring arrived at the edges of things—the old miracle—she stepped outside. Dew stitched the lawn with silver thread. Down the street a paper landed with the forgiving thud of a promise kept by a tired man. She put her palm to the brass, felt the warmth there, not hot, not cold. She thought of the thousand times she and Frank had left this house and the thousand times they’d returned, hands full of groceries or stories or just the satisfaction of having gone and come back in a world where that isn’t guaranteed.

“Thank you,” she told the light, which is to say she told the years, which is to say she told herself.

Daniel came with coffee and caution. They visited the cemetery and then the diner where the waitress called everyone love without making it cheap. They told Emma stories about the grandfather who once made a snowman so tall it embarrassed the sky. They drove home slowly because the world is rarely in as much of a hurry as we are.

On the porch that evening, the maple practicing its shadow tricks, Daniel said, “Mom, we could put in a motion sensor. Then the light comes on when someone is there and saves energy when no one is.”

“The light doesn’t need a reason to be kind,” she said. “It needs practice.”

He laughed. “Okay,” he said, because he had learned the art of surrender in small doses. “I’ll worry less if you promise to call at night. Just a hello.”

“I can do that,” she said.

He stood to go and then didn’t, because leaving our people is a process. “Do you… do you leave it on for Dad?” he asked, like a boy again.

Helen thought of answers like stepping stones: Yes. No. For me. She took Daniel’s hand. “I leave it on because we all come home in pieces,” she said. “Some piece of someone might need help finding the door.”

He nodded. He kissed her hair. He walked down the path and lifted his hand without looking back, the way men signal onward to those who understand what onward costs.

After dark, she sat in the chair by the door and listened to the hum. The light made an oval on the steps as tidy as an embroidered napkin. Moths practiced being bad at decisions. Somewhere a trumpet floated from an open window a street away, the notes brave and green as new leaves. She wondered if Emma would pick music or mathematics, or both, and then decided she didn’t have to choose for her. She wondered if Joseph would write, or just live, which is an honest letter on its own.

When she finally rose, bones arguing amiably with muscles, she paused at the knob. The house had settled around her like a cat willing to share a chair. She could turn the light off. No one had ordered otherwise. She could, and perhaps someday she would, because someday even rituals retire with dignity.

But not yet. Not with the maples whispering and the night walking as if it had permission. Not with the phone sleeping and the recipe box holding letters and lemon bars in equal measure. Not with a spare bulb waiting in a box like faith in the back of a drawer.

She touched the brass. It gave back a small warmth. She lowered her hand and let the light go on doing what it did best: telling the dark where they lived.

She never turned the light off.

Not because she was afraid.

Because she knew what it meant to be found.

News

He Gave Four Women Unlimited Credit Cards in New York—and What the Maid Did Changed Everything

New York glowed beneath a drizzle that refused to stop.From his penthouse overlooking Central Park, Ethan Caldwell watched the city…

A Rainy Morning in Atlanta—and the Promise That Changed Two Lives

Rain drifted across the windows of the little convenience store on Auburn Avenue, Atlanta.The kind of soft southern rain that…

The Porch Light in Virginia—and the Promise a Father Forgot

Norfolk, Virginia, just before dawn.The street still held the hush of sleep. Rain tapped a slow rhythm against the porch…

THE IVORY MUG IN MICHIGAN — WHERE SILENCE BREWED LOUDER THAN WORDS

The first snow of December had started to fall over Maple Creek, Michigan, a town that looked prettier from a…

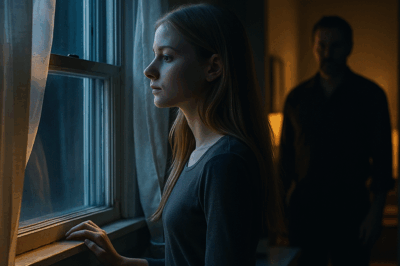

THE WINDOW THAT WOULDN’T CLOSE IN OHIO — WHERE LOVE BECAME A SECRET LANGUAGE

The wind pressed softly against the windows of a small house outside Columbus, Ohio.The curtains moved as if the air…

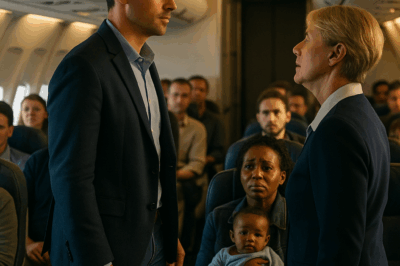

A Crying Baby, a Racist Slap, and One Man’s Stand That Restored Everyone’s Faith in Humanity

The Silence Before the Slap It’s strange how quiet an airplane can become when something terrible happens. Not the comfortable…

End of content

No more pages to load